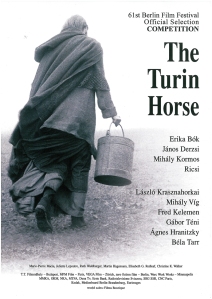

There are 30 shots in all in Hungarian couple Béla Tarr’s and Ágnes Hranitzky’s The Turin Horse (2011), 29 of which involve a moving camera and most of which are elaborately choreographed amalgam of camera movements. The first and possibly the most exhilarating shot of the film is a compounded crane and tracking shot in which we are presented with a horse cart and its driver. The dolly tracks at the pace of the cart and its craning arm films the cart primarily from two directions perpendicular to each other: a view lateral to the line of action and a view of the horse head-on and up close. (This combination of lateral and head-on angles of the camera will form a major visual motif in the film.) We see the horse pushing hard against the gale, with its mane fluttering backward. We see the man, equally haggard, with his hair swept back by the wind like the mane. We also note that, by himself, the man is static while the horse is the one moving forward and taking him along – a minor detail but also an illustration of the film’s chief theme. The equivalence between the horse and its driver becomes even more pointed as the film cuts to the second shot, where we see the man – now on foot – pulling the horse into the stable (also reiterated in shot no.22 where the man’s daughter does the pulling). After the second shot, the film shifts indoors, where the major part of the film unfolds.

Inside, we follow the man, Ohlsdorfer (Janos Derzsi), and his daughter (Erika Bok, who plays a counterpoint of sorts to the character she played 17 years ago in Satantango (1994)) as they go about doing their daily work for 6 consecutive days: she gets up first, wears the countless number of clothes hanging on the wall, adds firewood to the hearth, fetches water from the well, dresses up the man, who has a paralyzed right hand, and boils the potatoes so that they can have lunch. Much of the action involves, as does the latest Dardennes feature, closing and opening of doors, necessitated by the beastly windstorm that plagues the outdoors. Their house is sparse and functionally furnished. Not only are the walls entirely unadorned, but the coating is coming off. The man seems to be a cobbler and he, possibly, sells the belts he makes in the town. The family does not seem to particularly religious. It does not have appear to any neighbours or visitors, save for the man (Mihály Kormos) who comes to their house to get his keg of country liquor filled, and the band of gypsies which arrives at their well for water, only to be shooed off by the old man.

The day-to-day events repeat over and over, of course, but Tarr (Please rest assured that I’m not forgetting the contribution of Hranitzky here and elsewhere) and regular DoP Fred Keleman photograph them from different setups each day, trying out various possible configurations and presentations and as if illustrating the Nietzsche’s concept of Eternal Recurrence that informs the structuring of the film. The effect of ritualization and repetition of everyday events with religiosity is bolstered by Mihaly Vig’s characteristically organ-laden cyclical soundtrack (reminiscent of the thematically apt Que Sera Sera of Almanac of Fall (1985)) that meets its counterpoint only in the boisterousness of the winds that sweep the plain. Keleman and Tarr light and shoot the interior of the house so painstakingly and evocatively, that even commonplace objects achieve a throbbing vitality of their own. They often light overhead, as they regularly do, imparting a luminous visual profile to the characters, who now seem like spectres haunting this dilapidated house. Unusually, there are also few instances of a voice over, which is new for Tarr, which acts as like the voice of an anti-God looking over the man and his daughter during the course of the film and their eventual fall.

It soon appears as though the horse (Risci) is neither at the centre of the film’s lean narrative nor at the focus of its apparent ideas. Indeed, it simply looms in the background like an unwelcome guest or an illness that is preventing the old man from riding into town to do business. However, actually, the animal not only provides a stark thematic contrast to the human characters of the film, it is at the very foundation of its metaphysics. The film opens with a hearsay anecdote about Friedrich Nietzsche. Apparently, in January 1889, when the philosopher was in Turin, he witnessed a cart driver flogging his recalcitrant horse. Nietzsche is said to have stopped him in haste and leapt on to the cart, embraced the horse and cried profusely. It is also said that this was the day after which he started losing control of his mental faculties. Of course, at the outset, what Nietzsche felt was simple empathy for a tormented creature, like any kind person would have. But because the person we are talking about is Nietzsche, the event holds a very special implication. What he was going through was also a sudden experience of intersubjectivity and, as importantly, the awareness of its existence.

A small detour to Dostoyevsky, a writer Nietzsche deeply admired, would be instructive here. In Crime and Punishment (1865), protagonist Rodion Raskolnikov, a bona-fide Nietzschean character, is haunted by dreams of a horse being cudgeled to death for the entertainment of those around it. It is, in addition, an expression of the owner’s power over and possession of it. Rodion, who believes that certain superior individuals have the right to disregard law and conventional morality if they feel that they are doing so for a greater good, discovers here the fallacy of his worldview. Like Nietzsche, he proposes a philosophy of guilt predicated on the effect of a “crime” on the conscience of the actor and not on the acted upon. But what this idea assumes is that moral consciousness of a person is a given, fully-formed whole, independent of other consciousnesses. Rodion realizes, in this nightmare, the toxicity of appointing oneself a superordinate being, especially when the relationship is that of master and slave, owner and owned. Nietzsche, in a classic case of life is imitating art, faces the same situation at Turin. His tears are an acknowledgement of the interconnectedness of all consciousnesses, an equivalence of each one of them.

The opening text of The Turin Horse tells us that we know what happened to Nietzsche after the incident but not the horse. The film’s recognition of the horse as a being as important as Nietzsche begins right there. The first image we see is that of a mare trotting against heavy wind, very close to the screen, dominating the frame – as if the camera is embracing it – suggesting its centrality to the film’s ideas. (Actually, we are never told that this animal is the same as the one Nietzsche wept for. The cut from the anecdote to the horse prompts us to assume that. This is only the first instance of lack of specificity that pervades the film.) The Turin Horse treats the horse as a fully-formed consciousness in itself – as vital as, if not more, its human counterparts – capable of understanding the world and, more crucially, reacting to it. The two human characters at the centre of the film do recognize the doom that surrounds them, but do not seem to do anything to change or respond to it. On the other hand, it is their horse that protests the cruelty of its master and offers resistance to the decay all around by refusing to eat or work. In other words, the mare seems to possess a higher degree of self-awareness than its human owners. In one shot, the camera lingers on the horse long after the humans have left the scene, with the same solemnity that it displayed towards the people in the film. It is not some overblown anthropomorphism that we are dealing with here. It is a radical decentering of humanity as the locus of consciousness.

This tendency to displace humans as the centre of the universe also furthers Tarr’s and frequent collaborator László Krasznahorkai’s long-standing anti-Biblical programme. If, with the ending of Satantango and the upshot of the Nietzschean Werckmeister Harmonies (2000), the writer-director pair tried to overturn the Scripture, here they take on the Creation narrative itself. Divided into six days, which no doubt serve to echo the six days of the creation of earth, The Turin Horse chronicles in detail the progressive disintegration of the world back to nothingness before time. In this anti-Genesis-narrative, neither is man created in the image of God (one that’s not dead, that is), nor are beasts inferior beings to be tamed and controlled by man. (“Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.“) In Tarr’s and Krasznahorkai’s Scripture, it becomes increasingly difficult to separate night from day, the seasons from each other. (There are only two seasons in the film’s world – windy and otherwise). Beings, instead of being fruitful and multiplying, become scarcer and scarcer. Earth returns to the formless void – the void that we witness in the evocative last shot – that it was at the Beginning. One imagines that the film would agree with Genesis on the seventh day: “Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all the host of them”.

[The Turin Horse (2011) Trailer]

Commentators have noted the striking silent film-like appearance of The Turin Horse. Indeed, Tarr, who has never been as metafilmic, parallels the anti-Creation narrative with a similar trajectory on the cinematic plane. A number of sub-shots are presented with the set and character in full view, arranged against a flat background and shot head-on with the décor in parallel to the image plane, just like a silent movie. Many of the shots are parenthesized by vertical or horizontal bars of film grain that wipe across the screen. Father and daughter, themselves, resemble the monstrously mismatched prospectors of The Gold Rush (1925), eating a non-meal every day and the smaller one always drawing the shorter straw. This is compounded by the fact that the film is set in 1889, just about the time cinema came into being. Moreover, the two interruptions that disturb the routine of the silent family are marked by excessive talk and cacophony. The film begins with pure movement of cinema and ends in absolute stasis of photography. (It is telling, in this respect, that the only completely still shot of the film is the last one.) It is as though cinema, like the film’s world, has regressed into non-existence, from broad daylight to total darkness.

Judge him, but this affinity for depicting disintegration to rubble has permeated Béla Tarr’s filmography. In a way, each of his film is a document of structural destruction: of urban spaces (Family Nest, 1979), of the modern family (Prefab People, 1982), of society (Almanac of Fall, 1985), of political machinery (Satantango, 1994), of civility (Damnation, 1988) and of civilization (Prologue, 2004). The Turin Horse takes the logic further and locates itself at the probable end of humanity itself. If Tarr’s latest work appears to lack the analytical rigour or satirical edge of his previous films, it is because it distills key ideas of these earlier films into a highly abstract conceptual examination devoid of urgency and pointedness. Looking at the director’s oeuvre, one can see this coming. Tarr started with very topical, socially critical films made in vérité aesthetic. Realizing that surface realism could only get him this far, he took a stylistic as well as epistemological break with Almanac of Fall, after which, instead of recording reality as it appears, he dealt with increasingly abstracted forms removed from everyday experience and a philosophy that replaced materialism with metaphysics.

Such departicularization is the modus operandi of The Turin Horse. The film systematically removes any trace of specificity from within it and builds an extremely generic framework that one can liken to the confident broad strokes of a paintbrush. Such sucking away of particulars would have been fatal in a film with concrete political ambition. But The Turin Horse, in contrast, works in a philosophical and cinematic realm so rarified that such distillation seems tailor made for it. Beyond the very specific opening story (Who: Friedrich Nietzsche; Where: Door No. 6, Via Carlo Alberto, Turin; When: January 3rd, 1889), we are not sure about any narrative detail. The place could be Turin, or not. The year could be 1889, or not. It could be autumn, or not. The long monologue that the first visitor delivers is what Pauline Kael would call a Christmas tree speech: you can hang all your allegories on it. What is the threat he is talking about? Why is the town ruined? Who are “they”? We don’t get any answer. If, at all, Tarr makes another film and intends to take the idea further, he’s, in all possibility, going to find himself in the realm of pure avant-garde, with nothing concrete to hold on to except the truth of photography.

Undoubtedly, Tarr is as cynical as filmmakers can get. His cynicism, like Kubrick’s, is the cynicism of great art, to borrow a sentence from Rivette. But with The Turin Horse, Tarr seems to have punched through to the zone beyond. We have, here, entered the realm of the absurd, where cynicism itself is rendered impotent. In this film, doom is a given, inevitable. Instead of charting people’s downward spiral into the abyss as in the previous films, Tarr and team observe with resignation the insularity of people from their situation. Foreboding gives way to fatalism, cynicism to amusement. Robert Koehler correctly compares the film to the works of Samuel Beckett and The Turin Horse is a veritable adaptation of Waiting for Godot (1953). Right from the lone tree on hill top, through the dilemmas of vegetable eating, the sudden logorrhea of a stranger, the perpetually cyclical nature of events, to the ritualization of actions, especially the changing of apparels, Tarr’s incomplete tragicomedy in 30 shots echoes Beckett’s incomplete tragicomedy in two acts. Like Beckett’s bickering pair, or Buñuel’s angels, father and daughter find themselves unable to leave the house for some reason. And like Vladmir and Estragon, or Pinky and Brain (“Tomorrow we’ll try again”), the two– stuck in their house for eternity with only each other to stand witness for their existence – sit by the window everyday gazing at, or waiting for, a Godot that could be anything ranging from revolution to death.

But there are two key cinematic predecessors to The Turin Horse as well. The first of them, Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (1976), lends Tarr’s film its finely spiral structure, in which a continuous process of disintegration is made palpable by minute changes in what appear to be unchangeable routines. Like in Jeanne Dielman, another film with an inclination for culinary detailing, the aquarium-like world of the characters is pierced by changes in the outside world, leading to their downfall. Then there is Sohrab Shahid Saless’ Still Life (1974) with which The Turin Horse not only shares its strong comic undercurrent, but also the idea of rendering chronology and the passing of time irrelevant by making it go in loops; the eternal return if you will. But, unlike the makers of these two films, Tarr filters his film from any direct comment on contemporary social organization. (Akerman and Saless, on the other hand, are keenly focused on the issue of urban and rural alienation). But what these films, most critically, share is an acute eye for everyday details, for minor behavioral and physical variations and an unshakeable faith on inescapable specificity of the photographic image.

Rating: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

October 9, 2011 at 11:40 pm

Thank you for this, Srikanth: a truly wonderful piece!

LikeLike

October 10, 2011 at 7:39 am

Thank you, Girish!

LikeLike

October 10, 2011 at 11:24 am

Excellent article JAFB, so many ideas ! I hope I can get to see the film soon.

LikeLike

October 10, 2011 at 11:28 am

Thanks LC. I hope you do too.

LikeLike

October 10, 2011 at 3:07 pm

Excellent review – it made me watch the film once again, because at the first time it seems I missed too much, and now I feel mentally better equipped for another “difficult” viewing. Isn’t such an effect one of the reasons why critics like to write a “re-view”? Thank you!

LikeLike

October 10, 2011 at 3:09 pm

Thanks Dorothea. I guess writing a review itself amounts to a rewatch of sorts.

Cheers!

LikeLike

October 16, 2011 at 5:14 pm

How true!

LikeLike

November 13, 2011 at 12:13 am

loved your review, it helped clarify a lot of what i was thinking after watching the movie today. especially love the way you end your piece. this is the first movie by tarr i saw, and perhaps the entry was slightly eased by the fact that i’d read waiting for godot first.

what i felt while watching the turin horse was a subtle difference in the personality of the two characters, the woman and her father. brought out for me visibly first by the way they deal with their potatoes. the old man savaging the potato, the other being more careful as she eats. also the way they both interact with the horse. and that first long scene with its amazing piece of music got so under my skin that every time later that music played, especially insistently, i found the visual on screen overlapping with the opening scene running through my head. also the music does have an interesting variation when the gypsies arrive in all their loudness.

LikeLike

January 29, 2012 at 1:40 am

They go away just to arrive back! Wonderful.

The camera makes cinema active and this piece of art is the perfect example. “Art and nothing but art”, said Nietzsche, “We have art in order not to die of the truth.” Cinema had to cease, the camera had to die too. Just so the truth (death) prevails.

A masterpiece!

–The mother’s portrait. A memory of creation? The hope? Any thoughts?

LikeLike

February 3, 2014 at 4:26 am

A true film review. Thank you!

LikeLike

August 22, 2015 at 7:51 am

[…] topside of what gradually develops into an entropic negativizing of the scenario. The film moves, as one critic has astutely pointed out, from the “pure movement of cinema” to “the absolute stasis of photography.” (One is […]

LikeLike