It was the best of years, it was the worst of years. Best because a dizzying number of big and important projects surfaced this year and worst because I haven’t even been able to see even a fraction of that number, even though my film viewing hit an all-time high this December, That last bit was possible thanks to the city’s major international film festival, the first full-fledged fest that I’ve ever attended – a key event as far as my cinephilia is concerned. Although, I must admit, none of the new titles I saw at the fest blew me away, I was surprised by a handful of films that I think deserve wider exposure. (I’m thinking specifically of Jean-Jacques Jauffret’s debut film Heat Wave, a tragic, graceful hyperlionk movie in which piecing together the disorienting geography of Marseilles becomes as important as piecing together the four intersecting narratives.) Instead of continuing apologetically to emphasize my viewing gaps and to rationalize the countless number of entries on my to-see list, I present you another list, The Top 10 Films I Didn’t See This Year: (1) House of Tolerance (Bertrand Bonello, an indisputable masterpiece, probably) (2) Seeking the Monkey King (Ken Jacobs) (3) Margaret (Kenneth Lonergan) (4) This is Not a Film (Jafar Panahi/Mojtaba Mirtahmasb) (5) Century of Birthing (Lav Diaz) (6) Life Without Principle (Johnnie To) (7) The Loneliest Planet (Julia Loktev) (8) Hugo (Martin Scorsese) (9) Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Nuri Bilge Ceylan) (10) La Havre (Aki Kaurismaki). Now that that’s out of my system, here are my favorites from the ones I did get to see.

1. The Turin Horse (Béla Tarr/Ágnes Hranitzky, Hungary)

For a number of films this year, the end of the world became some sort of a theme park ride taken with ease, but none of them ventured as far as Béla Tarr’s mesmerizing, awe-inspiring farewell to cinema. With The Turin Horse, Tarr’s filmmaking traverses the whole gamut, moving away from the wordy realist pictures of his early phase to this extreme abstraction suggesting, in Godard’s phrasing, a farewell to language itself. Centering on a man, his daughter and their horse as they eke out a skeletal existence in some damned plain somewhere in Europe, The Turin Horse is the last chapter of a testament never written, an anti-Genesis narrative that finds God forsaking the world and leaving it to beings on earth to sort it all out by themselves. Tarr’s film is a remarkable cinematic achievement, primal in its physicality and elemental in its force. Nothing this year was so laden with doom and so brimming with hope at once as the ultimate image of the film, where father and daughter – now awakened, perhaps – sit in the darkness with nothing to confront but each other.

For a number of films this year, the end of the world became some sort of a theme park ride taken with ease, but none of them ventured as far as Béla Tarr’s mesmerizing, awe-inspiring farewell to cinema. With The Turin Horse, Tarr’s filmmaking traverses the whole gamut, moving away from the wordy realist pictures of his early phase to this extreme abstraction suggesting, in Godard’s phrasing, a farewell to language itself. Centering on a man, his daughter and their horse as they eke out a skeletal existence in some damned plain somewhere in Europe, The Turin Horse is the last chapter of a testament never written, an anti-Genesis narrative that finds God forsaking the world and leaving it to beings on earth to sort it all out by themselves. Tarr’s film is a remarkable cinematic achievement, primal in its physicality and elemental in its force. Nothing this year was so laden with doom and so brimming with hope at once as the ultimate image of the film, where father and daughter – now awakened, perhaps – sit in the darkness with nothing to confront but each other.

2. A Separation (Asghar Farhadi, Iran)

Asghar Farhadi’s super-modest yet supremely ambitious chronicle of class conflict in Tehran is a massive deconstruction project that strikes right at the heart of systems that define us. Accumulating detail upon detail and soaking the film in the ambiguity that characterizes the real world, A Separation reveals the utter failure of binary logic – which not only forms the foundation of institutions such as justice but also permeates and petrifies our imagination – in dealing with human dilemmas. Farhadi’s centrism is not a form of bourgeois neutrality that plagues many a war movies, it is a recognition that truth lies somewhere in the recesses between the contours of language, law and logic. Working with unquantifiable parameters such as irrationality and doubt, Farhadi’s film is something of an aporia in the discourses that surround cinema and reality and an urgent call for revaluation of approaches towards critical problems in general. Rigorously shot, edited and directed, A Separation is a genuinely empathetic yet highly intelligent slice of reality in all its messy complexity and breathtaking grace.

Asghar Farhadi’s super-modest yet supremely ambitious chronicle of class conflict in Tehran is a massive deconstruction project that strikes right at the heart of systems that define us. Accumulating detail upon detail and soaking the film in the ambiguity that characterizes the real world, A Separation reveals the utter failure of binary logic – which not only forms the foundation of institutions such as justice but also permeates and petrifies our imagination – in dealing with human dilemmas. Farhadi’s centrism is not a form of bourgeois neutrality that plagues many a war movies, it is a recognition that truth lies somewhere in the recesses between the contours of language, law and logic. Working with unquantifiable parameters such as irrationality and doubt, Farhadi’s film is something of an aporia in the discourses that surround cinema and reality and an urgent call for revaluation of approaches towards critical problems in general. Rigorously shot, edited and directed, A Separation is a genuinely empathetic yet highly intelligent slice of reality in all its messy complexity and breathtaking grace.

3. The Tree Of Life (Terrence Malick, USA)

Juxtaposing the cosmic, the macroscopic and the infinite with the particular, the everyday and the finite, Terrence Malick’s fifth film The Tree of Life seeks to ask big questions. It is here that the director’s longstanding philosophical concerns find perfect articulation and efficacy in the specific form of the film. Seamlessly shifting between perspectives both all-knowing and limited, The Tree of Life posits the existence of a single shared consciousness across time and place, only a small part of which is each human being. It is also Malick’s most phenomenological film and mostly unfolds as a series of sensory impressions that both invites and resists interpretation. An awe-instilling tug-of-war between finitude and permanence, omniscience and ignorance, narrativization and immediate experience and rationalization and incomprehension, Malick’s unabashed celebration of the birth of consciousness – in general and in specific forms – locates the particular in the universal and vice versa. What lingers in the mind more than the grand ideas, though, are extremely minor details, which is pretty much what the medium must aspire to achieve.

Juxtaposing the cosmic, the macroscopic and the infinite with the particular, the everyday and the finite, Terrence Malick’s fifth film The Tree of Life seeks to ask big questions. It is here that the director’s longstanding philosophical concerns find perfect articulation and efficacy in the specific form of the film. Seamlessly shifting between perspectives both all-knowing and limited, The Tree of Life posits the existence of a single shared consciousness across time and place, only a small part of which is each human being. It is also Malick’s most phenomenological film and mostly unfolds as a series of sensory impressions that both invites and resists interpretation. An awe-instilling tug-of-war between finitude and permanence, omniscience and ignorance, narrativization and immediate experience and rationalization and incomprehension, Malick’s unabashed celebration of the birth of consciousness – in general and in specific forms – locates the particular in the universal and vice versa. What lingers in the mind more than the grand ideas, though, are extremely minor details, which is pretty much what the medium must aspire to achieve.

4. The Story Of Film: An Odyssey (Mark Cousins, UK)

A scandalous history, a disproportionate sense of importance and a frustrating accent. Critic-Filmmaker Mark Cousins’ project to present the story of cinema as a 15-part TV series appears doomed right from the conceptualization stage: can you even attempt to tell a story of film without omitting whole schools of filmmaking or national cinemas? Omit it certainly does, and unapologetically so, but when Cousins chronologically hops from one country to another, halting at particular films, scenes or even shots, providing commentary that is as insightful as they come and situating them in the larger scheme of things, you wouldn’t hesitate to lower your guard. Not only does Cousins’ 900-minute tribute to filmdom introduce us to names in world cinema rarely discussed about, but also presents newer approaches to canonical entries. Admirably inclusive (Matthew Barney and Baz Luhrmann find adjacent seats, so do Youssef Chahine and Steven Spielberg) and never condescending, The Story of Film exhibits towards the history of the form a sensitivity comparable to the finest of film criticism.

A scandalous history, a disproportionate sense of importance and a frustrating accent. Critic-Filmmaker Mark Cousins’ project to present the story of cinema as a 15-part TV series appears doomed right from the conceptualization stage: can you even attempt to tell a story of film without omitting whole schools of filmmaking or national cinemas? Omit it certainly does, and unapologetically so, but when Cousins chronologically hops from one country to another, halting at particular films, scenes or even shots, providing commentary that is as insightful as they come and situating them in the larger scheme of things, you wouldn’t hesitate to lower your guard. Not only does Cousins’ 900-minute tribute to filmdom introduce us to names in world cinema rarely discussed about, but also presents newer approaches to canonical entries. Admirably inclusive (Matthew Barney and Baz Luhrmann find adjacent seats, so do Youssef Chahine and Steven Spielberg) and never condescending, The Story of Film exhibits towards the history of the form a sensitivity comparable to the finest of film criticism.

5. We Need To Talk About Kevin (Lynne Ramsay, UK)

What is stressed in Lynne Ramsay’s rattling third feature We Need to Talk About Kevin is not only the continuity between mother and son, but also the essential discontinuity. Where does the mother end and where does the son begin? Every inch of space between actors resonates with this dreadful ambiguity. The film is as much about Eva’s birth from the stifling womb of motherhood as it is Kevin’s apparent inability to be severed from her umbilical cord. Every visual in Ramsay’s chronicle of blood and birth works on three levels – literal, symbolic and associative – the last of which links the images of the film in subtle, subconscious and thoroughly unsettling ways. For the outcast Eva, the past bleeds into the present and every object, sound and gesture becomes a living, breathing reminder of whatever has been put behind. Ramsay’s intuitive, sensual approach to colour, composition and sound locates her directly in the tradition of the Surrealists and deems this unnerving, shattering, personal genre work as one of the most exciting pieces of cinema this year.

What is stressed in Lynne Ramsay’s rattling third feature We Need to Talk About Kevin is not only the continuity between mother and son, but also the essential discontinuity. Where does the mother end and where does the son begin? Every inch of space between actors resonates with this dreadful ambiguity. The film is as much about Eva’s birth from the stifling womb of motherhood as it is Kevin’s apparent inability to be severed from her umbilical cord. Every visual in Ramsay’s chronicle of blood and birth works on three levels – literal, symbolic and associative – the last of which links the images of the film in subtle, subconscious and thoroughly unsettling ways. For the outcast Eva, the past bleeds into the present and every object, sound and gesture becomes a living, breathing reminder of whatever has been put behind. Ramsay’s intuitive, sensual approach to colour, composition and sound locates her directly in the tradition of the Surrealists and deems this unnerving, shattering, personal genre work as one of the most exciting pieces of cinema this year.

6. Life In A Day (Various, Various)

An heir to the ideas of Dziga Vertov and Aleksandr Medvedkin, Kevin Macdonald’s Life in a Day is a moving, bewildering, charming, frustrating and dizzying snapshot of Planet Earth in all its glory, stupidity and complexity on a single day in 2011. An endless interplay of presence and absence, familiar and exotic, lack and excess, similarity and difference, the homogenous and the un-normalizable and the empowered and the marginalized, Life in a Day is a virtually inexhaustible film that is a strong testament to how many of us lived together on this particular planet on this particular day of this particular year. (That it represents only a cross section of the world population is a complaint that is subsumed by the film’s observations.) Each shot, loaded with so much cultural content, acts as a synecdoche, suggesting a dense social, political and historical network underneath. Most importantly, it taps right into the dread of death that accompanies cinematography: the heightened awareness of the finitude of existence and experience and the direct confrontation with the passing of time.

An heir to the ideas of Dziga Vertov and Aleksandr Medvedkin, Kevin Macdonald’s Life in a Day is a moving, bewildering, charming, frustrating and dizzying snapshot of Planet Earth in all its glory, stupidity and complexity on a single day in 2011. An endless interplay of presence and absence, familiar and exotic, lack and excess, similarity and difference, the homogenous and the un-normalizable and the empowered and the marginalized, Life in a Day is a virtually inexhaustible film that is a strong testament to how many of us lived together on this particular planet on this particular day of this particular year. (That it represents only a cross section of the world population is a complaint that is subsumed by the film’s observations.) Each shot, loaded with so much cultural content, acts as a synecdoche, suggesting a dense social, political and historical network underneath. Most importantly, it taps right into the dread of death that accompanies cinematography: the heightened awareness of the finitude of existence and experience and the direct confrontation with the passing of time.

7. Kill List (Ben Wheatley, UK)

On the surface, Ben Wheatley’s Kill List comes across like a sick B-movie with a mischievous sense of plotting, but on closer examination, it reveals itself as a serious work with clear-cut philosophical and political inclination. That its philosophy is inseparable from its mind-bending narrative structure makes it a very challenging beast. Kill List is the kind of kick in the gut that video games must strive to emulate if they aspire to become art. Indeed, Wheatley’s chameleon of a film borrows much from video games – from its division of a mission into stages announced by intertitles to the third-person-shooter aesthetic that it segues into – making us complicit with the protagonist and his moral attitude, later pulling the rug from our feet and leaving us afloat. Early in the film, Iraq war veteran and protagonist Jay mumbles that it was better if he was fighting the Nazis – at least, he would know who the enemy was. He learns the hard way that this ‘othering’ of the enemy into a mass of unidentifiable groups is a psychological strategy to protect and redeem himself, that it’s judgment that defeats us.

On the surface, Ben Wheatley’s Kill List comes across like a sick B-movie with a mischievous sense of plotting, but on closer examination, it reveals itself as a serious work with clear-cut philosophical and political inclination. That its philosophy is inseparable from its mind-bending narrative structure makes it a very challenging beast. Kill List is the kind of kick in the gut that video games must strive to emulate if they aspire to become art. Indeed, Wheatley’s chameleon of a film borrows much from video games – from its division of a mission into stages announced by intertitles to the third-person-shooter aesthetic that it segues into – making us complicit with the protagonist and his moral attitude, later pulling the rug from our feet and leaving us afloat. Early in the film, Iraq war veteran and protagonist Jay mumbles that it was better if he was fighting the Nazis – at least, he would know who the enemy was. He learns the hard way that this ‘othering’ of the enemy into a mass of unidentifiable groups is a psychological strategy to protect and redeem himself, that it’s judgment that defeats us.

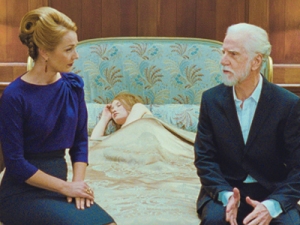

8. Sleeping Beauty (Julia Leigh, Australia)

“Your vagina will be a temple” one elderly procurer assures Lucy, a twenty something university student who takes up odd jobs to pay her fees. Not only is the vagina a temple in Julia Leigh’s markedly assured debut feature, but the human body itself is a space that is to be furnished, maintained and rented out for public use. Leigh’s vehemently anti-realist examination of continuous privatization of the public and publicization of the private works against any kind of psychological or sociological realism, instead unfolding as an academic study of the human body as a site of control. Setting up a dialectic between pristine, clinical public spaces and messy, emotional private ones, Sleeping Beauty attempts to explore not our relationship to the spaces that we inhabit, but also to the space that we ourselves are. Consistently baffling and irreducible, Leigh’s film displays an eccentric yet surefooted approach to design, composition and framing, revealing the presence of a personality beneath. Sleeping Beauty is, for me, the most impressive debut film of the year.

“Your vagina will be a temple” one elderly procurer assures Lucy, a twenty something university student who takes up odd jobs to pay her fees. Not only is the vagina a temple in Julia Leigh’s markedly assured debut feature, but the human body itself is a space that is to be furnished, maintained and rented out for public use. Leigh’s vehemently anti-realist examination of continuous privatization of the public and publicization of the private works against any kind of psychological or sociological realism, instead unfolding as an academic study of the human body as a site of control. Setting up a dialectic between pristine, clinical public spaces and messy, emotional private ones, Sleeping Beauty attempts to explore not our relationship to the spaces that we inhabit, but also to the space that we ourselves are. Consistently baffling and irreducible, Leigh’s film displays an eccentric yet surefooted approach to design, composition and framing, revealing the presence of a personality beneath. Sleeping Beauty is, for me, the most impressive debut film of the year.

9. The Kid With A Bike (Jean-Pierre Dardenne/Luc Dardenne, Belgium/France)

The Dardenne brothers have turned out to be the preeminent documentarians of our world and their latest wonder The Kid with a Bike sits alongside their best works as an unadorned, incisive portrait of our time. Admittedly inspired by fairly tales, Dardennes’ film might appear like an archetypal illustration of innocence lured by the devil, but its parameters are all drawn from here and now. Structured as a series of transactions – persons, objects, moral grounds – where human interaction is inextricably bound to the movement of physical objects, the film presents our world as one defined by exchanges of all kind, but never reduces this observation to some cynical reading of life as a business. Also characteristic of Dardennes’ universe is the intense physicality that pervades each shot. Be it the boy scurrying about on foot or on bike or the countless number of doors that are opened and closed, the Dardennes, once more, show us that cinema must concern itself with superficies and it is on the surface of things that one can find depth.

The Dardenne brothers have turned out to be the preeminent documentarians of our world and their latest wonder The Kid with a Bike sits alongside their best works as an unadorned, incisive portrait of our time. Admittedly inspired by fairly tales, Dardennes’ film might appear like an archetypal illustration of innocence lured by the devil, but its parameters are all drawn from here and now. Structured as a series of transactions – persons, objects, moral grounds – where human interaction is inextricably bound to the movement of physical objects, the film presents our world as one defined by exchanges of all kind, but never reduces this observation to some cynical reading of life as a business. Also characteristic of Dardennes’ universe is the intense physicality that pervades each shot. Be it the boy scurrying about on foot or on bike or the countless number of doors that are opened and closed, the Dardennes, once more, show us that cinema must concern itself with superficies and it is on the surface of things that one can find depth.

10. The Monk (Dominik Moll, France/Spain)

Dominik Moll’s adaptation of Matthew Lewis’ eponymous novel concerning a self-righteous priest tempted by the devil could be described as an intervention of late nineteenth century tools – psychoanalysis and cinema – into a late eighteenth century text. Located on this side of the birth of psychoanalysis, Moll’s film comes across as essentially Freudian in the way it portrays the titular monk as a human being flawed by design and the church, society and family as institutions responsible for suppressing those basic impulses. Incest, rape and murder abound as hell breaks loose, but the film’s sympathy is clearly with the devil. The Monk uses an array of early silent cinema techniques including a schema that combines an impressionistic illustration of the protagonist’s sensory experience and expressionistic mise en scène to signal his irreversible descent into decadence. Alternating between metallic blues of the night and sun bathed brown, Moll’s film teeters on the obscure boundary between Good and Evil. Exquisitely composed and expertly realized, The Monk supplies that irresistible dose of classicism missing in the other films on this list.

Dominik Moll’s adaptation of Matthew Lewis’ eponymous novel concerning a self-righteous priest tempted by the devil could be described as an intervention of late nineteenth century tools – psychoanalysis and cinema – into a late eighteenth century text. Located on this side of the birth of psychoanalysis, Moll’s film comes across as essentially Freudian in the way it portrays the titular monk as a human being flawed by design and the church, society and family as institutions responsible for suppressing those basic impulses. Incest, rape and murder abound as hell breaks loose, but the film’s sympathy is clearly with the devil. The Monk uses an array of early silent cinema techniques including a schema that combines an impressionistic illustration of the protagonist’s sensory experience and expressionistic mise en scène to signal his irreversible descent into decadence. Alternating between metallic blues of the night and sun bathed brown, Moll’s film teeters on the obscure boundary between Good and Evil. Exquisitely composed and expertly realized, The Monk supplies that irresistible dose of classicism missing in the other films on this list.

January 2, 2012 at 12:14 am

Nice list. I haven’t seen anything you haven’t seen and in the list of the films you have seen, I have seen two (A Separation, Kid with a Bike) 20% is not bad considering how many movies you seen :)

So you did not include ‘Melancholia’ in your top 10?

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 7:33 am

Glad that many have gotten to see my favorite films this year. Doesn’t happen often. Yes, MELANCHOLIA was a b underwhelming for me.

Cheers!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 8:46 am

Exactly the same feeling I had about MELANCHOLIA. Ofcourse the director’s control is visible but overall the film was underwhelming with its rather pessimistic philosophy.

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 12:57 am

Happy 2012 JAFB! Some interesting films in your list that I haven’t seen yet. Mark Cousins voyage was epic and I can concur that it deserves its place in the top ten. The Turin Horse looks somewhat special and can’t wait for that one to appear in the local cinema. Your initial list of films you haven’t seen is also tantalising especially Ceylan’s film. I will have to watch Sleeping Beauty – I don’t know why I stepped away from that one. What of your Bangalore cinephile expedition? Will you be posting any of your musings on the films you watched? By the way, what were your favourite Indian films of 2011? Best wishes to another another awesome year of film gazing and writing!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 7:37 am

Thanks Omar! I thought I would not put up a summation of the fest because I’d already done that on Twitter, film by film. But yes, why not?!

Didn’t see as many Indian films as I wanted in 2011. I liked 7 KHOON MAAF and AADUKALAM a lot. (I loved DHOBI GHAT, but still consider it a 2010 entry). If I am to take some resolution this year, it would be to watch more local films, even though I find most of the promos disappointing.

Thanks again and a happy new year to you too, Omar.

Cheers!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 2:40 am

Fantastic list here Srikanth, that again shows you as such a tasteful and discerning cineaste! Two of your very top film (A SEPARATION and THE TREE OF LIFE will be among my own Top 4 films of the year in a comparable presentation set for January 9th at my site. I like KEVIN, but still found some issues, which would preclude it from making my own planned Top 20 list. Your intriguing 6 to 10 placement are in consideration of films that have not yet opened stateside, hence could not be under consideration for this year. I am particularly interested in the Dardenne film, but the others are all under my radar too.

Cousin’s THE STORY OF FILM is now in my possession (sent from Allan) and I am most eager to find the time to watch it, but it wouldn’t count as an option based on my rules, which require theatrical opening stateside in 2011.

You had OF GODS AND MEN on last year’s list, so I can’t bemoan it’s omission here. It will finish in my Top 10. I am rather surprised you didn’t have MYSTERIES OF LISBON nor MELANCHOLIA (TOMBOY, SHAME, THE ARTIST and DRIVE are others that are noted by their absence) but I can’t question what DID MAKE YOUR LIST, as everything here is stunning in every sense. As to THE TURIN HORSE I am still debating where that will place on my own list–it is excellent, though for me not quite with WERCKMEISTER HARMONIES and SATANTANGO, and not quite a contender for the top 10. (Top 20 is possible) It’s an audacious #1 pick by an equally audacious blogger critic!

Happy New Year to you and yours my friend!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 7:39 am

Thanks for those ever-generous worlds, Sam. I have a feeling you won’t be disappointed by Cousins’ series.

I haven’t yet seen LISBON (and consider it as a 2010 entry), TOMBOY, SHAME or THE ARTIST, but will surely do in the near future.

Wishing you a terrific new year ahead, Sam!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 3:37 am

Jealous as hell you got to see Le Moine, JAFB. The French DVD as always was subless. Also need to see Sleeping Beauty again on Blu Ray. It left me cold on first viewing but it had a quality about it, for sure, and Emily Browning was superbly docile.

Nice to see some love for the Cousins, too.

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 7:41 am

Allan (?),

THE MONK was sneaky, I didn’t even think I’d like it. Yes, please reconsider Leigh’s film It has been given such a raw deal (along with KEVIN) by critics.

Cheers and a very very happy new year!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 6:35 pm

I don’t need to reconsider Kevin, that’s an exceptional film and the UK reviews and those at Cannes were a lot stronger than the US – and far more reliable. Even Sleeping Beauty got solid OK reviews including from Empire and Total Film surprisingly.

The one I want to see is the Bonello, but there’s no Eng subbed print out there. Will have to wait for a DVD but that won’t be till summer as the French DVD doesn’t have Eng subs.

Happy new year to you, too, JAFB. Even though the first two initials are too modest.

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 9:17 pm

Thank you so much, Allan. I’d kill to see the Bonello.

Cheers!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 4:11 am

Really nice to see The Story of Film show up on a list, JAFB. I’ve been slowly making my way through it, and have really been enjoying it so far. Of course any attempt at an all-encompassing project like this will almost always leave itself open to some warranted criticisms, but the ambition is admirable and the appreciation deeply felt. From the rest of your list I also really liked The Kid With A Bike, Sleeping Beauty and The Tree of Life.

I’ve been struggling a lot with We Need To Talk About Kevin; I thought it was a pretty staggering formalist accomplishment, but it felt kind of confused and self-offsetting to me: trying to forge some kind of nature/nurture dialectic on the one hand, and constantly returning back to this exaggerated evil-child horror imagery on the other. I loved Ramsay’s first two movies, so I plan on viewing it again to see if I can further clarify my thoughts and feelings towards it. I also saw Kill List recently, and thought it was really well done, but I was left with this weird feeling that its primary concerns didn’t really extend much beyond a game of one-upmanship with previous exercises in horror-oriented genre-bending and portrayals of cabalistic nefariousness, so your comments regarding its political and philosophical leanings make me anxious to give it another watch soon and see if I can get a handle on some of the stuff that I missed the first time around.

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 7:47 am

Thanks for those elaborate comments about KEVIN and KILL List, Drew.

I’m still mulling over KILL LIST and I think this one is a fast grower. I’d like to see it again as well. As for KEVIN, I do understand the criticisms. But I’d say that that this ambiguity regarding parenthood (Am I my son’s keeper?) is what is precisely enriched by the refraction through the present. I love that there’s not attempt at unwarranted psychological explanation for Kevin’s actions (video games, pot, heavy metal etc.) and the lingering possibility that he might just be acting nasty on purpose. Ramsay acknowledges the limitation of that approach and contains the film in the realm of the purely personal. I was overwhelmed by the film.

Thank you and wishing you a wonderful year ahead, Drew.

Cheers!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 8:54 am

Great list, and I love your overvew of THE TURIN HORSE – a wonderful summation of an incredible film. Your “Films I Haven’t Seen” list uncannily matches films I also have yet to see and am keenyl anticipating, (bar THIS IS NOT A FILM, which I’ve already seen and can vouch for it’s absolute brilliance.) I’m yearning to see Ken Jacobs’ new work.

A number of films on your list are also films I’ve yet to see – A SEPARATION and KILL LIST are two that I’m very keen on seeing in the new year. I’ve been wanting to get hold of Mark Cousins’ epic historical sweep of cinema, but your words compel me to seek this out as soon as possible.

Happy viewing and blogging for the new year!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 9:12 pm

Thanks for the kind words, Michael. I can guarantee that A SEPARATION will sweep you off your feet!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 9:37 am

As always JAFB you have an stupendous list of pure 2011 films (as I’m always glad to read) and this one is one to really applaude. Some of these choices are really brave, smart and at the same time… correct.

Of course “The Turin Horse” is one of the best films of 2011, it manages to create a world on its own using so many shots (33, the age of Christ, as I read somewhere), giving us a story of sacrifice that isn’t actual self sacrifice, but of sacrifice due to the circumstances and one where God (as you note in the capsule) abandon us to the wolves and then send us to death.

“A Separation” was my pick for the best movie of the year for a lot of time (that changed about one month ago), but still is one of the best iranian movies I’ve seen and one of the bravest when it comes down to the social aspects of the country and how this almost hitchcockian tale of mystery and drama goes around leaving us with a certain distaste of “what is the human being really capable of?” or just “hey, I’d do that too”, it feels suspenseful, but it never feels unreal.

“The Tree of Life” was a film I didn’t connect with. It felt like a teacher giving me headlines on how to live my own life, and the constant shouts of “MOTHER” “FATHER” “BROTHER” where the most annoying thing about it. I still found beauty in the cinematography and those still and simpler moments (not that I hated the universe stuff, I loved it) where the kids are playing around, doing nothing, with no voiceover to interrupt them.

We talked on twitter about how much I liked “We Need to Talk About Kevin” and yet at the same time how I understood the raise of negative responses regarding the tone and the overall “style over substance”, but you nail it here with your writing, on how the visual style works with the substance behind it, going beyond it and working between images. And that’s besides the great performance of Swinton (you should do a Best Actor/Actress/Cin thing).

My comment in your “Life in a Day” piece is my final assestment, it’s a great film and in my own top 10 list.

I liked “The Kid with a Bike” a lot, as it manages to show the enormous potential that the Dardennes have with a bit more of freedom, citing new elements to include in their films, like the inclusion of music, a new thing for the Dardennes (I think).

On the rest, I can say I haven’t seen them. But maybe I will.

GREAT LIST!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 9:17 pm

Jaime,

Let me return that compliment for your own super-interesting list (whose details I will not spoil here). It is one of the most exciting ones out there and your #1 has piqued my interest like crazy. I hadn’t, like many other I’m sure, even heard of that particular filmmaker. I did seek out the neat little Error Morris film after I saw it on your list. Can’t wait to see the whole six hour interview.

And thanks so much for this very detailed comment. I have my own minor reservations with THE TREE OF LIFE, but the major part of the film is just too incredible.

Thanks again and a very happy new year to you!

LikeLike

January 3, 2012 at 1:24 am

I had forgotten that I had already shown my in the works list.

LikeLike

January 3, 2012 at 1:25 am

I forgot that I had already shown my “in the works” list to a few people already.

And my top 1 will be hard to get whenever it comes out. It’s a hard film to sell.

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 10:20 am

Excellent list–even a couple that I haven’t heard of, The Story of Film and The Monk, that I look forward to catching up with. I wrestled with Kill List, and ultimately left it off my list, but I have a felling it might prove richer on a second viewing. Also, I agree with your Turin Horse enthusiasm–check out my list on ECSTATIC, if you get a chance: http://jason-hedrick.blogspot.com/

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 9:20 pm

Jason,

WAR HORSE is, all of a sudden, being raved all over. Must check that out as soon as possible. I dig that there’s a soft corner for RANGO, which I thought was very inspired. And CAVE OF FORGOTTEN DREAMS is my favorite Herzog in a long, long time, perhaps since WINGS OF HOPE.

Thanks and Cheers!

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 9:02 pm

‘The Turin Horse’ is not only the best of the year but it is a land mark film in the history of cinema of the world. If it is the farewell piece of art from Bela Tarr, it is again making history. Though I have not seen all the films included in the list, I think it is not complete without including “Faust” by Sokurov. However we have to wait and see what better films can improve this list.

LikeLike

January 2, 2012 at 9:21 pm

I haven’t seen FAUST, Kishore, and I hope to see it soon. I’m sure there are even more wonderful films slipping the critical radar. 2012 will have to reveal them.

Cheers!

LikeLike

January 4, 2012 at 1:04 am

The issue I do have with THE TURIN HORSE is that it won’t get a USA opening until the summer of 2012 (later this year). By my own way of negotiating ten-best lists, it will count for next December, much like OF GODS AND MEN, which made your own list last year, but will make my own this year. But this is a minor point of delineation, one that has caused you Srikanth, much grieve in your e mail inbox.

Please accept my apologies for this my friend. I won’t be quick to pull the trigger on comment threads in the future.

LikeLike

January 4, 2012 at 7:24 am

That’s OK, Sam. I understand. Just choose a method and stick to it, I’m not as interested in the premiere dates as I am about the titles themselves. Slant had A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY on their list, which is about 20 years late.

No need for apologies! I’ve been enjoying the banter actually. Cheers!

LikeLike

January 4, 2012 at 8:41 am

Oh God, yes, Srikanth! That SLANT decision caused another email explosion thread with most of the WitD people opposing the SLANT decision. I seemed to be the only one who thought the decision to go with it was fair enough. Several years back the New York Film Critics Circle even went earlier by picking “Army of Shadows” as Best Foreign Film, even though it released in 1969.

LikeLike

January 5, 2012 at 2:51 am

*comment tangential to the topic at hand*

While I’m yet to watch Kill List [and also cultivate an overall better taste in cinema ;) ], allow me to ramble about video games a bit. Games are evolving as a major art form already, albeit the sort of treatment and pleasure they provide are somewhat different from movies –this partially explains why most movies based on PC games are such a sham (thats a different matter that no Hollywood studio has made a serious attempt to remain true to the theme and treatment of the original property; also the reason why much acclaimed Half Life, like many other top rated games, has not been allowed to be made in a movie yet).

However, apart from being pure visual delight (ex- Flower from Sony Entertainment), there indeed are some serious efforts happening in the gaming field particularly in the indie gaming genre (try LIMBO, a mere 70mb game, but extremely intense and touching; or Bioshock which really makes a person think while making choices).

As always, I look forward to your blog to understand and sharpen the depth, subtlety, shades and treatment of films.

Keep the great work!

PS: Wishlist: A review and analysis of the Russian movie by Andrei Tarkovsky called ‘Stalker’ :)

LikeLike

January 5, 2012 at 7:42 am

Thanks for bringing that into discussion, Amatya Rakshas.

This is a link that needs to be explored. Yes, by the sheer amount of creativity that goes into video games (American McGee, Sid Meier), it would be of little surprise if truly great games are out there already. But even the best ones that I’ve played move into an Us vs Them mode. Even the ones that are conscious about their construction (Serious Sam saga, Hitman series), haven’t done much to blow me away. Of course, I need to sample more games to temper my perception.

Thanks and cheers!

LikeLike

January 5, 2012 at 8:24 am

I’ve toyed with the idea of having seen a playthrough or a let’s play of a videogame counts as a movie.

If that is true, the playthrough of Portal 2 would be in my top 5, even if I haven’t played it myself.

LikeLike

January 5, 2012 at 10:09 pm

I missed most of these, but then I didn’t even see 10 films from 2011, let alone these 10. For me it was a year of engaging with the history of movies, and my own history with them, before moving on to address the future. Thus, the perfect way to wrap up the year was to watch The Story of Film, which I’m thrilled to see on your list!

Put me in the “fan” category; after finishing it, I was surprised to see it had so many detractors online, mostly due to Cousins’ accent (or rather, unique vocal stylization) which I found amusing rather than offputting. I loved the scale and ambition of the film, combined with its desire to reinvent and expand the conventional narrative of film history. I thought the doc was constructed rather well too – to sound a bit pretentious about it, the movie negotiated its identity as both a source of information and an aesthetic object itself rather well. Put less pretentiously, the quiet location shots were quite effective, the interviews really played a part (instead of just assembling a running commentary consistent with his own pre-determined structure, Cousins seemed to allow his subjects to help shape the material), and the clips were engaged with marvelously, much in the spirit of the better DVD commentaries and the newly emerging form of video essay.

Some of the stylistic touches may come to seem a bit dated down the line, but all in all I think this will hold up well as a pleasurable and informative survey of a great medium.

Aside from that, I saw only Tree of Life, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, and Drive among 2011 releases. I will probably see Melancholia in a few days. All were noteworthy.

One thing I like about your list is that several of the films seem quite ambitious. There is always a place for the intensely focused, minimalist masterpiece on any list of great art but it seems to me that lately there has been a dearth of the grand, ambitious works – particularly in a popular vein. While I’m not sure there’s much that fits both those categories (the disconnect between art and entertainment cinema has become disconcerting) at least there seemed to be a lot of ambition in cinema this past year – from Tree of Life to Story of Film to Life in a Day. I like seeing filmmakers think big.

Thanks for the write-ups, Srikanth, and hope 2012 treats you well.

LikeLike

January 5, 2012 at 10:42 pm

Thank you very much, Joel.

Frankly, I think I’d like to get away from this minor fad of catching up with new films and making year end lists some time in the future. I’d be glad if I could engage positively with films – whatever they are, even a bunch of YouTube videos – learn and bring something on to the table. So I’m as excited reading lists of favorite films SEEN in 2011 as I’m lists of favorite films of 2011.

Re: THE STORY OF FILM. I sorta guessed that this would not go down well with many people (especially the accent, yes, which sounded to me like a very long reminder to someone who has forgotten his cinema). But that is not my major problem. Cousins uses the auteur theory as a standard to explore cinema as an enterprise based on innovation/passion – as opposed to box office – which is fine. What I was taken aback by is the use of auteur theory even at crucial points where it becomes moot. Case in point, Mani Kaul’s comments (midway in the series) on there being no subject (“I”) and that he is nothing but his films. What Kaul points out here, I think, is the absence of a solid consciousness behind works of art (decentering of subject), that films are entities independent of authorial intentionality or personality and are tied to networks larger than an individual. But Cousins, immediately, interprets Kaul’s comments to viewers as a variation of auteur theory, that every film is an unmistakable work of a single creator.

That gripe aside, I can’t see how a project that kept me occupied for a third of the year wouldn’t make this list. Any TV series that takes cinema seriously and tries to bring into popular attention ignored works and underrated artists is worthy in my books. But, THE STORY OF FILM is not ‘any’ series though. As you say, it transcends the pitfalls of classroom lectures or film-nerdiness (without dissing them) and instead tries to bring great films to popular attention without diminishing them. (For once, Kurosawa is not someone who just wrote amazing stories). So more power to Cousins.

The films of 2011 were surprising to me in the way they casually dealt with BIG IDEAS (although I must add that the two films of 2010 – yes, the year that sucked – I liked the most are much more incisive and ambitious than any film on this list). It’s almost as if the 50s have returned – every film is loaded.

WIshing you a great year ahead too, Joel.

P.S: You’ve already seen the brilliant VERTIGO VARIATIONS, haven’t you?

LikeLike

January 6, 2012 at 8:07 am

I’m rather an auteurist romantic myself, so I don’t mind that aspect so much. To me if there’s one big oversight to Cousins’ film it’s that he almost completely ignores animation, except for a bit on Disney, a clip from Trnka & later on CGI (i.e. inasmuch as it relates back to live-action).

I hadn’t heard of the Vertigo Variations until you mentioned it but I just read about on MUBI. I’ll have to watch it this weekend – maybe after I watch Family Plot tomorrow, which wraps up a 5-month personal Hitchcock retro. Good timing…

LikeLike

January 6, 2012 at 11:31 am

Joel,

Yes, lots of omissions no doubt, especially avant-garde (except for mentions of Barney and Anger). Re: VERTIGO VARIATIONS. It’s a gem, and an apt ending to your Hitch marathon I think, which sounds exciting.

Cheers!

LikeLike

January 6, 2012 at 12:58 am

Thanks for the list, curious and great read.

You didn’t include Oliveira’s “Strange Case of Angelica” in neither this nor previous year favorites. Wonder how did you rate it?

I am still pondering about “Tree of Life”. I personally disliked it genuinely and strongly while acknowledging its mastery. It might be the only 2011 film (although I haven’t seen “House of Tolerance”) which felt slightly like “a new cinema”. I found it rooted in time and space I have no connection to, dreadfully sentimental and kitchy in Kundera’s sense.

For Kundera, “Kitsch causes two tears to flow in quick succession. The first tear says: How nice to see children running on the grass! The second tear says: How nice to be moved, together with all mankind, by children running on the grass! It is the second tear that makes kitsch kitsch.” It is precisely the second tear which makes ToL a massive showing of human sentimentality. Instead of showing life, it shows human perception of it, at best, and old man’s rambling at worst.

LikeLike

January 6, 2012 at 11:27 am

Thank you, Paulius.

I’d seen ANGELICA after I’d posted my last year’s list. My revised list for 2010 would look something like this:

1. UNCLE BOONMEE 2. FILM SOCIALISME 3. HONEY 4. CERTIFIED COPY 5. MY JOY 6. THE STRANGE CASE OF ANGELICA 7. OF GODS AND MEN 8. NOSTALGIA FOR THE LIGHT 9. SHUTTER ISLAND 10. THE SOCIAL NETWORK.

I have problems with THE TREE OF LIFE as well. In fact, I have bigger problems on the same lines with rest of Malick (the same self-preciousness). The seeming all-knowing-ness of cosmic sequences did not work for me at all. And I’m not enraged by any criticism about it. On the other hand, the specificity and the sublimity of the Waco section (about 75% of the film) are among the very best of the year. It becomes, as you say, something of an exploration of consciousness about the world more than the world itself. I was awed.

LikeLike

January 6, 2012 at 5:25 pm

Srikant,

Great list. We agree on two of the 10. I haven’t seen The Turin Horse and The Boy on the Bicycle. I note that you have not seen Faust and possibly the Iranian film Goodbye. 2011 was a great year for good cinema!

LikeLike

January 6, 2012 at 5:28 pm

Thanks Jugu,

You are right. I haven’t seen FAUST or GOODBYE. Hope to see them this year.

Cheers!

LikeLike

January 7, 2012 at 11:17 am

An exceptional & eclectic list – but then what else can one expect from a cineaste-par-excellence like you. I’m far from having seen most of the acclaimed 2011 movies, so lists like yours are acting as sources of quick references for me since I intend to watch at least a few of the good ones before it’s too late.

And, by the way, Srikanth, aka JAFB, wish you a slightly belated Happy New Year!!! :)

LikeLike

January 7, 2012 at 11:26 am

Thanks for the kind words, Shubhajit. A belated happy new year to you too!

LikeLike

January 19, 2012 at 6:59 pm

A very nice list! I have 3 of those in my top 10 foreign films of the year, though like you there are still many films I have yet to see.

LikeLike

January 22, 2012 at 11:58 pm

Thank you, BT.

LikeLike