2025 was disappointing, even frustrating in both personal and historical terms. At the beginning of the year, I had set myself simple goals, all of which I failed at. My reading plummeted to almost zero, as did my public writing. I had hoped to add more entries to the Curator’s Corner column, but it was not to be. A few projects and opportunities that I was looking forward to didn’t materialize. Not to mention a host of health issues and family emergencies.

The political optimism of 2024 proved not just short lived, but derisory given the impunity with which the lunatics in power and their rabid supporters continued to destroy everything decent, human and life-sustaining. In India, state and market censorship alike have reached absurd levels, awards are now so compromised as to make satirists twiddle their thumbs, festivals are pushed to the brink of dysfunction by a philistine information ministry, naked propaganda seems to be the only way to box-office salvation, critics have been harassed by industry insiders and barbaric hordes on social media for precisely doing their job, celebrities continue to toe the line or silence themselves out of a justified fear of reprisal. All this, just in the domain of cinema.

The only respite for me came in the form of encounters with interesting, reasonable and committed people, especially at the Jakarta Film Week and International Film Festival Kerala, both of which I attended for the first time. The passion and the international camaraderie that I witnessed were welcome assurances that, no matter its immediate currency, bigotry and parochialism will forever be uncool.

In more solitary undertakings, I had the chance to explore parts of Indian documentary history I was unfamiliar with. Among these, I strongly recommend Chalam Bennurkar’s Children of Mini-Japan (1990), Anjali Monteiro and K.P. Jayasankar’s YCP 1997 (1997), David MacDougall’s Doon School Quintet (2000-04), Deepa Dhanraj’s Invoking Justice (2011) and especially R.V. Ramani’s My Camera and Tsunami (2011).

Besides acclaimed and popular films from Kerala made after 2010, I also caught up on a significant swathe of Malayalam cinema from the 80s and the 90s. This included two canonical masterpieces in Perumthachan (1991) and Ponthan Mada (1994) in addition to numerous remarkable features emerging from a short, bountiful period of heightened creativity: Irakal (1985), Deshadanakkili Karayarilla (1986), Thaniyavarthanam (1987), Amrutham Gamaya (1987), Ponmuttayidunna Tharavu (1988), Dasharatham (1989), Varavelpu (1989), Sandhesam (1991), Bharatham (1991) and Njan Gandharvan (1991), to name but a few. Farewell Sreenivasan, the recently departed actor-director-screenwriter behind many of these titles.

As always, the following list is based on an arbitrary eligibility criterion: films that had a world premiere in 2025.

1. Happiness (Firat Yücel, Turkey/Netherlands)

Fatigued and sleep deprived, a Turkish filmmaker in Amsterdam tries to find ways to reduce his excessive screen usage and catch some shuteye. But the horrors of the world, beamed onto digital screens in real time, know no respite. Firat Yücel’s extraordinary desktop essay departs from this premise in all directions, only to return to it with new insights and dizzyingly far-reaching associations. Tracing the agonized drifts of a sensitive, hyperconnected mind, Happiness lays bare a highly contemporary double bind: if the screens we are hooked to keep us away from living in the real world, it is these very screens that helps us make sense of our lived experiences. The filmmaker’s investigation into his bodily malaise leads him to unpack its historical conditions: the colonial legacy that underpins the prosperity of his host country, its flourishing happiness industry and its dubious foreign policies. Yücel’s inward observation takes him ever outward; his exasperation at the immediate present, into the distant past. Rigorous as it is witty and playful, Happiness perfectly embodies the agitations of the modern liberal consciousness, present everywhere and nowhere at once, all too aware of the immensity of human misery as well as its own impotence in the face of it. [World Premiere: Visions du Réel]

Fatigued and sleep deprived, a Turkish filmmaker in Amsterdam tries to find ways to reduce his excessive screen usage and catch some shuteye. But the horrors of the world, beamed onto digital screens in real time, know no respite. Firat Yücel’s extraordinary desktop essay departs from this premise in all directions, only to return to it with new insights and dizzyingly far-reaching associations. Tracing the agonized drifts of a sensitive, hyperconnected mind, Happiness lays bare a highly contemporary double bind: if the screens we are hooked to keep us away from living in the real world, it is these very screens that helps us make sense of our lived experiences. The filmmaker’s investigation into his bodily malaise leads him to unpack its historical conditions: the colonial legacy that underpins the prosperity of his host country, its flourishing happiness industry and its dubious foreign policies. Yücel’s inward observation takes him ever outward; his exasperation at the immediate present, into the distant past. Rigorous as it is witty and playful, Happiness perfectly embodies the agitations of the modern liberal consciousness, present everywhere and nowhere at once, all too aware of the immensity of human misery as well as its own impotence in the face of it. [World Premiere: Visions du Réel]

2. Peter Hujar’s Day (Ira Sachs, USA)

Ira Sachs’ eminently cinematic re-creation of a tape-recorded conversation, from December 1974, between writer Linda Rosenkrantz (played by Rebecca Hall) and photographer Peter Hujar (Ben Whishaw) is an object lesson in the creative possibilities of redundancy, a vital illustration of how the film medium can actualize itself, not by shunning the written word but, on the contrary, by faithfully embracing it. Over 76 condensed minutes, Hujar recollects a day from his life in New York City in rigorous detail — a fascinating mix of the ordinary and the extraordinary, recalling The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975) — to an attentive, sympathetic Rosenkratz amid the changing light of his apartment. As Hujar’s endless stream of speech washes over us to the point of exhaustion, our focus turns from its specific content to the process by which memory becomes material. Drawing from transcripts of the conversation — and not Rosenkrantz’s original recording, now lost —Whishaw’s incredibly textured performance reveals the task of imaginative translation that underlies all actorly work. For all its thrilling verbosity, Sachs’s film is a tribute to the art of listening, to this intimate space of friendship in which the hierarchy between the memorable and the mundane ceases to exist. [WP: Sundance Film Festival]

Ira Sachs’ eminently cinematic re-creation of a tape-recorded conversation, from December 1974, between writer Linda Rosenkrantz (played by Rebecca Hall) and photographer Peter Hujar (Ben Whishaw) is an object lesson in the creative possibilities of redundancy, a vital illustration of how the film medium can actualize itself, not by shunning the written word but, on the contrary, by faithfully embracing it. Over 76 condensed minutes, Hujar recollects a day from his life in New York City in rigorous detail — a fascinating mix of the ordinary and the extraordinary, recalling The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975) — to an attentive, sympathetic Rosenkratz amid the changing light of his apartment. As Hujar’s endless stream of speech washes over us to the point of exhaustion, our focus turns from its specific content to the process by which memory becomes material. Drawing from transcripts of the conversation — and not Rosenkrantz’s original recording, now lost —Whishaw’s incredibly textured performance reveals the task of imaginative translation that underlies all actorly work. For all its thrilling verbosity, Sachs’s film is a tribute to the art of listening, to this intimate space of friendship in which the hierarchy between the memorable and the mundane ceases to exist. [WP: Sundance Film Festival]

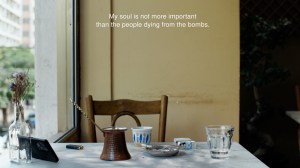

3. Manal Issa, 2024 (Elisabeth Subrin, Lebanon/USA)

Where Elisabeth Subrin’s powerful Maria Schneider, 1983 (2022) — based on a televised interview of the eponymous French actress — created doubles, Manal Issa, 2024 proposes a negation. Here, Subrin asks the Lebanese-French actress Manal Issa, one of the three participants of the former film, the same questions that Schneider was posed in the original interview. Vocal about her stances, Issa talks about the poverty of meaningful roles offered to Arab-origin actresses, the limitations of the capitalist production model, the choice of moving back to Lebanon during crisis and the importance of speaking up against political iniquity. She adds that she feels professionally isolated for voicing her opinions, for calling out Israel’s bombing of Gaza. While we listen to her responses, Issa herself remains offscreen, her refusal to sustain her career by censoring herself echoed by Subrin’s refusal to show her. “If I can’t be true to myself, there is no point showing myself,” the actress concludes. Like Schneider’s palpable reluctance, Issa’s self-negation stems from an outlook that privileges life over films, reality over fiction. Six hours after the shoot, an end card notes, “Israeli airstrikes escalated throughout Lebanon, killing over 500 people in one day.” [WP: Cinéma du Réel]

Where Elisabeth Subrin’s powerful Maria Schneider, 1983 (2022) — based on a televised interview of the eponymous French actress — created doubles, Manal Issa, 2024 proposes a negation. Here, Subrin asks the Lebanese-French actress Manal Issa, one of the three participants of the former film, the same questions that Schneider was posed in the original interview. Vocal about her stances, Issa talks about the poverty of meaningful roles offered to Arab-origin actresses, the limitations of the capitalist production model, the choice of moving back to Lebanon during crisis and the importance of speaking up against political iniquity. She adds that she feels professionally isolated for voicing her opinions, for calling out Israel’s bombing of Gaza. While we listen to her responses, Issa herself remains offscreen, her refusal to sustain her career by censoring herself echoed by Subrin’s refusal to show her. “If I can’t be true to myself, there is no point showing myself,” the actress concludes. Like Schneider’s palpable reluctance, Issa’s self-negation stems from an outlook that privileges life over films, reality over fiction. Six hours after the shoot, an end card notes, “Israeli airstrikes escalated throughout Lebanon, killing over 500 people in one day.” [WP: Cinéma du Réel]

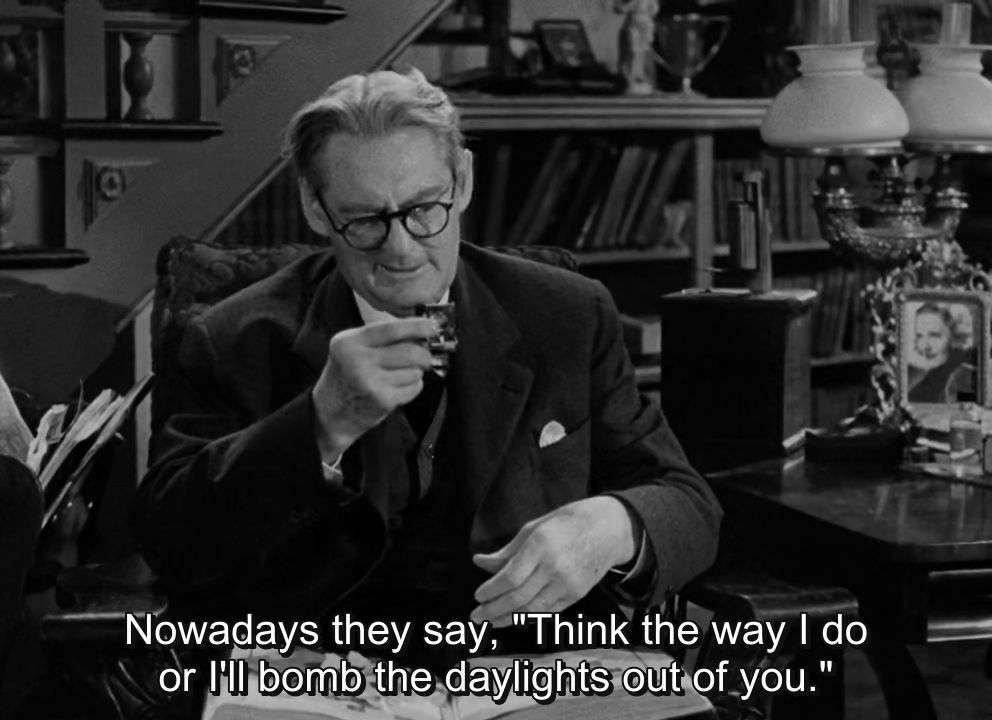

4. One Battle After Another (Paul Thomas Anderson, USA)

All appeal is sexual, political appeal especially so. Among other things, Paul Thomas Anderson’s wild, action-filled, hysterically funny ride through a caricatural America torn between white supremacists and antifa insurgents — each more paranoid than the other about imagined contaminations — lays bare the erotic drive animating ideological cohesion (and ideological sabotage). Leonardo DiCaprio’s failed revolutionary, mentally arrested in the 1970s, and Sean Penn’s boyish, waif-like sergeant are twisted projections of each other’s fears. Whether the film is reactionary, apolitical or progressive is beside the point. This is a work by an artist who contemplates a polarized society, its excesses and its mess-ups with sage amusement, or a stoner’s delight, without giving in to cynicism or misanthropy. DiCaprio delivers the performance of the year in a movie filled with performances of the year, each one on a different register, all of it nevertheless brought into perfect harmony by dint of sheer directorial orchestration. One Battle After Another stands tall in a movie culture dominated by safe, anaemic films calculated to say the right things and avoid broaching the wrong things. It made me wish we had more filmmakers who actually felt something between their legs. [WP: international commercial release]

All appeal is sexual, political appeal especially so. Among other things, Paul Thomas Anderson’s wild, action-filled, hysterically funny ride through a caricatural America torn between white supremacists and antifa insurgents — each more paranoid than the other about imagined contaminations — lays bare the erotic drive animating ideological cohesion (and ideological sabotage). Leonardo DiCaprio’s failed revolutionary, mentally arrested in the 1970s, and Sean Penn’s boyish, waif-like sergeant are twisted projections of each other’s fears. Whether the film is reactionary, apolitical or progressive is beside the point. This is a work by an artist who contemplates a polarized society, its excesses and its mess-ups with sage amusement, or a stoner’s delight, without giving in to cynicism or misanthropy. DiCaprio delivers the performance of the year in a movie filled with performances of the year, each one on a different register, all of it nevertheless brought into perfect harmony by dint of sheer directorial orchestration. One Battle After Another stands tall in a movie culture dominated by safe, anaemic films calculated to say the right things and avoid broaching the wrong things. It made me wish we had more filmmakers who actually felt something between their legs. [WP: international commercial release]

5. Beyond the Mast (Mohammad Nuruzzaman, Bangladesh)

In this rapturous slice-of-life portrait, a small commercial boat with an all-male crew goes from port to port along a river in Bangladesh selling oil. When the crew’s kindly cook takes a stowaway child under his aegis, he runs afoul of the boat’s ill-tempered, scheming helmsman, covetous of the captain’s job. Despite a good deal of on-board intrigue, there is very little drama, strictly speaking, in Mohammad Nuruzzaman’s artisanal second feature, which doesn’t even seek to create lyrical moments in the vein of, say, Satyajit Ray. Yet, this is a highly poetic work, the poetry arising primarily from the filmmaker’s intent, non-judgmental way of looking at a small, enclosed world, its rituals, its diverse people and their human foibles: touches of jealousy, compassion, malevolence, ambition and camaraderie; a parade of life simply passing by. The form is meditative yet brisk — with very elegant camera choreography — and remains indifferent to fashionable arthouse formulas, stylistic shorthand or established screenplay structures. Even the film’s casual neo-realism doesn’t aim at traditional qualities of empathy and psychological description; it rather inspires Ozu-like contemplation. Just a lovingly crafted film. [WP: Moscow International Film Festival]

In this rapturous slice-of-life portrait, a small commercial boat with an all-male crew goes from port to port along a river in Bangladesh selling oil. When the crew’s kindly cook takes a stowaway child under his aegis, he runs afoul of the boat’s ill-tempered, scheming helmsman, covetous of the captain’s job. Despite a good deal of on-board intrigue, there is very little drama, strictly speaking, in Mohammad Nuruzzaman’s artisanal second feature, which doesn’t even seek to create lyrical moments in the vein of, say, Satyajit Ray. Yet, this is a highly poetic work, the poetry arising primarily from the filmmaker’s intent, non-judgmental way of looking at a small, enclosed world, its rituals, its diverse people and their human foibles: touches of jealousy, compassion, malevolence, ambition and camaraderie; a parade of life simply passing by. The form is meditative yet brisk — with very elegant camera choreography — and remains indifferent to fashionable arthouse formulas, stylistic shorthand or established screenplay structures. Even the film’s casual neo-realism doesn’t aim at traditional qualities of empathy and psychological description; it rather inspires Ozu-like contemplation. Just a lovingly crafted film. [WP: Moscow International Film Festival]

6. Roohrangi (Tusharr Madhavv, India/Netherlands)

With a camera in hand, a gay filmmaker from South Asia walks around in a park in Amsterdam known as a cruising hotspot. What he finds in this place of fleeting encounters is a kind of time warp, the apparent permanence of its majestic trees, their gnarled roots and variegated textures reminding him of his own roots back in Lucknow, India. They recall, in particular, his grandfather’s discoloured skin, caused by leukoderma, which made him look like a white man — a dual identity paralleling the filmmaker’s own. Echoing this image, Roohrangi starts to lose its colours too, shedding its skin to reveal various layers of memory, history and fantasy underlying a leisurely stroll, as different geographies and eras interpenetrate one another. Like in the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, the forest in Roohrangi is a liminal, essentially queer space that enables communion with other lives, other worlds — a glimpse into different possibilities of being. With curiosity and formal openness, Tusharr Madhavv mixes stylized, essayistic passages with casual interviews with the park’s denizens. The result is an evocative, visually striking work, at once experimental and accessible, that achieves the right balance of discursivity, mystery and invention. [WP: Ann Arbor Film Festival]

With a camera in hand, a gay filmmaker from South Asia walks around in a park in Amsterdam known as a cruising hotspot. What he finds in this place of fleeting encounters is a kind of time warp, the apparent permanence of its majestic trees, their gnarled roots and variegated textures reminding him of his own roots back in Lucknow, India. They recall, in particular, his grandfather’s discoloured skin, caused by leukoderma, which made him look like a white man — a dual identity paralleling the filmmaker’s own. Echoing this image, Roohrangi starts to lose its colours too, shedding its skin to reveal various layers of memory, history and fantasy underlying a leisurely stroll, as different geographies and eras interpenetrate one another. Like in the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, the forest in Roohrangi is a liminal, essentially queer space that enables communion with other lives, other worlds — a glimpse into different possibilities of being. With curiosity and formal openness, Tusharr Madhavv mixes stylized, essayistic passages with casual interviews with the park’s denizens. The result is an evocative, visually striking work, at once experimental and accessible, that achieves the right balance of discursivity, mystery and invention. [WP: Ann Arbor Film Festival]

7. Past Is Present (Shaheen Dill-Riaz, Germany/Bangladesh)

In 2007, Berlin-based Bangladeshi documentarian Shaheen Dill-Riaz found himself in the midst of a family scandal: while studying abroad, his sister Mitul had secretly married her cousin to the great chagrin of her parents. As this taboo union began to tear the family apart, Dill-Riaz decided to mediate between Mitul in Australia, his elder brother Amirul in the USA and his heartbroken parents back home in Dhaka. In Past Is Present, Dill-Riaz turns his camera onto himself and his dear ones, producing a sweeping domestic saga shot over fourteen years and across four continents. Tracing his parents’ journey from rural Bangladesh to Dhaka, and their three children’s subsequent drift to far-flung corners of the globe, the filmmaker examines the complex personal fallout of voluntary migration, presented here in all its liberating and melancholic dimensions. Dill-Riaz seamlessly interweaves moments of torrid drama with passages of mundane poetry, his handheld camera adopting a transparent, unassuming style. The film’s international narrative produces a startling contrast of textures and lifestyles, but also crystallizes the profound continuities in emotional and moral values across cultures. A touching study in the tyranny of distance, Past Is Present actualizes the immortal struggle between the home and the world. [WP: International Film Festival Rotterdam]

8. Obscure Night – Ain’t I a Child? (Sylvain George, France)

The concluding chapter of Sylvain George’s trilogy on illegal immigration is an extraordinary object of close, unflinching observation. The film follows three Tunisian teenagers who take temporary refuge in Paris after having been shuttled by immigration authorities across various cities in Western Europe. With remarkable intimacy and equanimity, George’s camera films the gang at slightly below the eye-level as they wander the roads of night-time Paris, huddle around fire, get into nasty fights with their Algerian counterparts, listen to street music or make the occasional phone call back home. An indifferent Eiffel Tower glitters perpetually in the background as the boys find themselves prisoners under an open sky. Shot in stark monochrome with eye-popping passages of abstraction, George’s film lends a monumental weight to images and lives we would rather not see. As a white artist making films on vulnerable sans papiers, George is bound to ruffle some feathers. But his film demonstrates that, sometimes, you need to strain certain ethical boundaries to arrive at newer forms of looking and understanding. Neither incriminating its subjects nor making any apology for them, Obscure Night – “Ain’t I a Child?” reveals the herculean difficulty of creating a truly humanist work. [WP: Visions du Réel]

The concluding chapter of Sylvain George’s trilogy on illegal immigration is an extraordinary object of close, unflinching observation. The film follows three Tunisian teenagers who take temporary refuge in Paris after having been shuttled by immigration authorities across various cities in Western Europe. With remarkable intimacy and equanimity, George’s camera films the gang at slightly below the eye-level as they wander the roads of night-time Paris, huddle around fire, get into nasty fights with their Algerian counterparts, listen to street music or make the occasional phone call back home. An indifferent Eiffel Tower glitters perpetually in the background as the boys find themselves prisoners under an open sky. Shot in stark monochrome with eye-popping passages of abstraction, George’s film lends a monumental weight to images and lives we would rather not see. As a white artist making films on vulnerable sans papiers, George is bound to ruffle some feathers. But his film demonstrates that, sometimes, you need to strain certain ethical boundaries to arrive at newer forms of looking and understanding. Neither incriminating its subjects nor making any apology for them, Obscure Night – “Ain’t I a Child?” reveals the herculean difficulty of creating a truly humanist work. [WP: Visions du Réel]

9. May the Soil Be Everywhere (Yehui Zhao, China/USA)

Yehui Zhao’s winsome debut feature begins as a personal documentary about the filmmaker’s search for her roots, but it gradually blooms into a sprawling examination of Chinese society and its evolving relationship to the land across modes of production. In her quest to unearth her family tree, the filmmaker finds herself peeling back layers upon layers of violent history — an excavation that takes her back to the soil, to a primordial ecology: caves that have now become sand mines, dogs that were once wolves, high-speed rail that now cut through unmarked graves. May the Soil Be Everywhere offers a rare and unusual glimpse into China’s pre-revolutionary past that takes us across vastly different terrains, time periods, generations: we learn of landlords who, during the revolution, became persecuted cave dwellers who then turned into Stakhanovite foot soldiers of Mao and are now digital filmmakers in a globalized world. The film’s direct and unaffected voiceover enables the overdone format of the personal documentary to break loose into a free-form essay featuring humorous animation and re-enacted tableaux. If the filmmaker’s attachment to familial lineage feels a little excessive, it undeniably carries a subversive force within post-revolutionary Chinese society. [WP: True/False Film Fest]

Yehui Zhao’s winsome debut feature begins as a personal documentary about the filmmaker’s search for her roots, but it gradually blooms into a sprawling examination of Chinese society and its evolving relationship to the land across modes of production. In her quest to unearth her family tree, the filmmaker finds herself peeling back layers upon layers of violent history — an excavation that takes her back to the soil, to a primordial ecology: caves that have now become sand mines, dogs that were once wolves, high-speed rail that now cut through unmarked graves. May the Soil Be Everywhere offers a rare and unusual glimpse into China’s pre-revolutionary past that takes us across vastly different terrains, time periods, generations: we learn of landlords who, during the revolution, became persecuted cave dwellers who then turned into Stakhanovite foot soldiers of Mao and are now digital filmmakers in a globalized world. The film’s direct and unaffected voiceover enables the overdone format of the personal documentary to break loose into a free-form essay featuring humorous animation and re-enacted tableaux. If the filmmaker’s attachment to familial lineage feels a little excessive, it undeniably carries a subversive force within post-revolutionary Chinese society. [WP: True/False Film Fest]

10. Admission (Quentin Hsu, Taiwan)

Panicked by the rejection of their six-year-old ward at an elite boarding school, an affluent tiger couple convenes an emergency meeting with their “fixer” and one of the school’s board members at a resort. Emerging from their negotiations and blame games is a stark portrait of a childhood labouring under someone else’s dreams. Quentin Hsu’s razor-sharp debut is a formalist kammerspiel that is Mungiu/Farhadi-like in its dissection of the moral corruption of the Chinese middle-class. But the approach to the material is entirely anti-naturalistic, pointedly theatrical. The film makes phenomenal use of its 4:3 aspect ratio and off-screen space, with the masquerade and subterfuge of the dramatic situation reflected in actors constantly gliding in and out of the frame, their bodies now eclipsed by the décor, now irrupting into the shot. The frame is constantly energized and de-energized by these microscopically choreographed movements in a way that recalls the Zürcher brothers. The actors are little more than props in the director’s precise, Kubrick-like design, but it’s bracing to witness a work that articulates its ideas through brute mise en scène, especially for a subject that would have called for a more psycho-realist treatment. [WP: Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival]

Panicked by the rejection of their six-year-old ward at an elite boarding school, an affluent tiger couple convenes an emergency meeting with their “fixer” and one of the school’s board members at a resort. Emerging from their negotiations and blame games is a stark portrait of a childhood labouring under someone else’s dreams. Quentin Hsu’s razor-sharp debut is a formalist kammerspiel that is Mungiu/Farhadi-like in its dissection of the moral corruption of the Chinese middle-class. But the approach to the material is entirely anti-naturalistic, pointedly theatrical. The film makes phenomenal use of its 4:3 aspect ratio and off-screen space, with the masquerade and subterfuge of the dramatic situation reflected in actors constantly gliding in and out of the frame, their bodies now eclipsed by the décor, now irrupting into the shot. The frame is constantly energized and de-energized by these microscopically choreographed movements in a way that recalls the Zürcher brothers. The actors are little more than props in the director’s precise, Kubrick-like design, but it’s bracing to witness a work that articulates its ideas through brute mise en scène, especially for a subject that would have called for a more psycho-realist treatment. [WP: Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival]

Special Mention: Living the Land (Huo Meng, China)

Favourite Films of

2024 • 2023 • 2022 • 2021 • 2020 • 2019

2015 • 2014 • 2013 • 2012 • 2011 • 2010 • 2009