2019 was a special year for me. I came back to cinema in an abiding way after a break of over three years. It was also this year that I quit my day job to write and translate full time, even if it has mostly been for this site. This second innings of my cinephilia has been more guarded, and I find it hard to be excited about watching this or that film, even if it’s by a favourite filmmaker. Part of the reason for this change, I think, is that I don’t repose as much faith in the taste-makers I was earlier guided by (major festivals, branded auteurs, critical consensus). This has weakened, if not completely collapsed, the structure in my mind of what constitutes important cinema of a particular year. Adding to this is the fact that the way I react to films has changed. In my writing, I see myself responding to certain aspects of a work rather than forming strong opinion on its overall merit. As a result, I’m as stimulated by lesser works with strong moments or ideas as I am by expectedly major projects. Whether this breaking down of hierarchies is a sign of openness to new things or a symptom of waning faith, I don’t know.

The state of affairs in the world outside cinema hasn’t been easy either. The staggering return of the politically repressed around the world has found an expression in some of this year’s films too (Zombi Child, The Dead Don’t Die, Atlantics, Ghost Town Anthology, Immortal). Personally speaking, the increasingly dire situation in India hasn’t been without its influence on the way I relate to cinema. The brazenness of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) has now paled in comparison to the mind-numbing institutional violence towards the ongoing protests against the act. Looking at videos of police brutality on my social media feed, I wondered, as anyone else involved in matters of lesser urgency must have, if writing about cinema at this point even had a personal significance, leave alone a broader, social one. The directness of the videos, the clarity of their meaning and the immediacy of their effect made me doubt whether cinematic literacy—contextualization, analysis, inference, interpretation—was a value worth striving for. Weakening of convictions is perhaps part of growing old, but it makes writing all the more difficult. Every utterance becomes provisional, crippled by dialectical thought. I don’t have a hope-instilling closing statement to give like Godard does in The Image Book, so here’s a top ten list instead. Happy new year.

0. 63 Up (Michael Apted, UK)

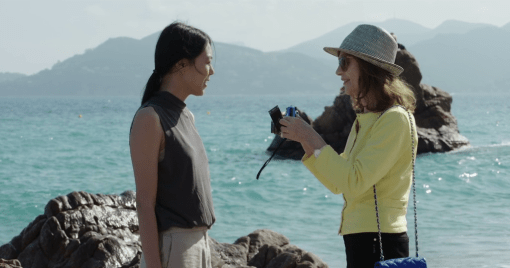

1. The Truth (Hirokazu Kore-eda, Japan/France)

While multiple films this year about old age have presented it as a time of reckoning, Kore-eda’s European project The Truth offers an honest, rigorous and profoundly generous picture of life’s twilight. In a career-summarizing role, Catherine Deneuve plays a creature of surfaces, a vain actress who struts in leopard skin and surrounds herself with her own posters. Her Fabienne is a pure shell without a core who can never speak in the first person. She has written an autobiography, but it’s a sanitized account, a reflection of how her life would rather have been. “Truth is boring”, she declares. Responding to her daughter Lumir’s (Juliette Binoche) complaint that she ignored her children for work, she bluntly states that she prefers to be a good actress than a good person. Behaviour precedes intent in the mise en abyme of Kore-eda’s intricate monument to aging, as performance becomes a means of expiation and a way of relating to the world. A work overflowing with sensual pleasures as well as radical propositions, The Truth rejects the dichotomy between actor and role, both in the cinematic and the existential sense. In the end, Fabienne and her close ones come together as something resembling a family. That, assures Kore-eda’s film, is good enough.

While multiple films this year about old age have presented it as a time of reckoning, Kore-eda’s European project The Truth offers an honest, rigorous and profoundly generous picture of life’s twilight. In a career-summarizing role, Catherine Deneuve plays a creature of surfaces, a vain actress who struts in leopard skin and surrounds herself with her own posters. Her Fabienne is a pure shell without a core who can never speak in the first person. She has written an autobiography, but it’s a sanitized account, a reflection of how her life would rather have been. “Truth is boring”, she declares. Responding to her daughter Lumir’s (Juliette Binoche) complaint that she ignored her children for work, she bluntly states that she prefers to be a good actress than a good person. Behaviour precedes intent in the mise en abyme of Kore-eda’s intricate monument to aging, as performance becomes a means of expiation and a way of relating to the world. A work overflowing with sensual pleasures as well as radical propositions, The Truth rejects the dichotomy between actor and role, both in the cinematic and the existential sense. In the end, Fabienne and her close ones come together as something resembling a family. That, assures Kore-eda’s film, is good enough.

2. Parasite (Bong Joon-ho, South Korea)

The across-the-board success of Parasite invites two possible inferences: either that the cynical logic of capital can steer a searing critique of itself to profitable ends or that this twisted tale of upward ascension appeals to widely-held anxiety and resentment. Whatever it is, Bong Joon-ho’s extraordinary, genre-bending work weds a compelling social parable to a vital, pulsating form that doesn’t speak to current times as much as activate something primal, mythical in the viewer. With a parodic bluntness reminiscent of the best of seventies cinema, Bong pits survivalist working-class resourcefulness with self-annihilating bourgeois prejudice and gullibility, the implied sexual anarchy never exactly coming to fruition. He orchestrates the narrative with the nimbleness and legerdemain of a seasoned magician, the viewer’s sympathy for any of the characters remaining contingent and constantly forced to realign itself from scene to scene. Parasite is foremost a masterclass in describing space, in the manner in which Bong synthesizes the bunker-like shanty of the working-class family with the high-modernist household of their upper-class employers, tracing direct metaphors for the film’s themes within its topology. It’s a work that progresses with the inevitability of a boulder running down a hill. And how spectacularly it comes crashing.

The across-the-board success of Parasite invites two possible inferences: either that the cynical logic of capital can steer a searing critique of itself to profitable ends or that this twisted tale of upward ascension appeals to widely-held anxiety and resentment. Whatever it is, Bong Joon-ho’s extraordinary, genre-bending work weds a compelling social parable to a vital, pulsating form that doesn’t speak to current times as much as activate something primal, mythical in the viewer. With a parodic bluntness reminiscent of the best of seventies cinema, Bong pits survivalist working-class resourcefulness with self-annihilating bourgeois prejudice and gullibility, the implied sexual anarchy never exactly coming to fruition. He orchestrates the narrative with the nimbleness and legerdemain of a seasoned magician, the viewer’s sympathy for any of the characters remaining contingent and constantly forced to realign itself from scene to scene. Parasite is foremost a masterclass in describing space, in the manner in which Bong synthesizes the bunker-like shanty of the working-class family with the high-modernist household of their upper-class employers, tracing direct metaphors for the film’s themes within its topology. It’s a work that progresses with the inevitability of a boulder running down a hill. And how spectacularly it comes crashing.

3. Vitalina Varela (Pedro Costa, Portugal)

Vitalina Varela is an emblem of mourning. In recreating a harrowing moment in her life for the film, the middle-aged Vitalina, who comes to Lisbon following her husband’s death, instils her loss with a meaning. It’s a film not of political justice but individual injustice, the promise to Vitalina the that men in their resignation and madness have forgotten. It’s also a bleak, relentless work of subtractions. What is shown is arrived at by chipping away what can’t/won’t be shown, this formal denuding reflective of the increasing dispossession of the Cova da Moura shantytown we see in the film. Costa’s Matisse-like delineation of figure only suggests humans, enacting the ethical problems of representation in its plastic scheme. The film is on a 4:3 aspect ratio, but the viewer hardly perceives that, the localized light reducing the visual field to small pockets of brightness. Vitalina is a film of and about objects, whose vanishing echoes the community’s dissolution and whose presence embodies Vitalina’s assertive spirit. Her voice has its own materiality, her speech becomes her means to survival. Costa’s film is a vision of utter despair, a cold monument with an uplifting, absolutely essential final shot. A dirge, in effect.

Vitalina Varela is an emblem of mourning. In recreating a harrowing moment in her life for the film, the middle-aged Vitalina, who comes to Lisbon following her husband’s death, instils her loss with a meaning. It’s a film not of political justice but individual injustice, the promise to Vitalina the that men in their resignation and madness have forgotten. It’s also a bleak, relentless work of subtractions. What is shown is arrived at by chipping away what can’t/won’t be shown, this formal denuding reflective of the increasing dispossession of the Cova da Moura shantytown we see in the film. Costa’s Matisse-like delineation of figure only suggests humans, enacting the ethical problems of representation in its plastic scheme. The film is on a 4:3 aspect ratio, but the viewer hardly perceives that, the localized light reducing the visual field to small pockets of brightness. Vitalina is a film of and about objects, whose vanishing echoes the community’s dissolution and whose presence embodies Vitalina’s assertive spirit. Her voice has its own materiality, her speech becomes her means to survival. Costa’s film is a vision of utter despair, a cold monument with an uplifting, absolutely essential final shot. A dirge, in effect.

4. Bird Island (Sergio da Costa & Maya Kosa, Switzerland)

The bird island of the title is a utopian place, a refuge for those wounded or cast aside by modernity. For sixty minutes, we are invited to look at five people working silently alongside each other in a bird shelter, tending to birds dazed by the airport next door. They don’t ask where these birds come from, nor do they expect them to leave soon. They simply treat the feathered creatures, re-habituate them into the wild and set them free. The reclusive Antonin, the new employee, is one such bird too, and his social healing at the shelter is at the heart of the film. Bird Island is full of violence, natural and man-made, all of which it treats with stoic acceptance, but it’s a work primarily about the curative power of community, the capacity for individuals to coexist in mutual recognition of each other’s frailties. In that, it’s the Catholic film par excellence, an allegory of the origin of religion. It’s also an exceptionally relaxing film to look at. Observing the participants absorbed like Carthusian monks in their individual tasks, even while working in a group, places the viewer on the same meditative state.

The bird island of the title is a utopian place, a refuge for those wounded or cast aside by modernity. For sixty minutes, we are invited to look at five people working silently alongside each other in a bird shelter, tending to birds dazed by the airport next door. They don’t ask where these birds come from, nor do they expect them to leave soon. They simply treat the feathered creatures, re-habituate them into the wild and set them free. The reclusive Antonin, the new employee, is one such bird too, and his social healing at the shelter is at the heart of the film. Bird Island is full of violence, natural and man-made, all of which it treats with stoic acceptance, but it’s a work primarily about the curative power of community, the capacity for individuals to coexist in mutual recognition of each other’s frailties. In that, it’s the Catholic film par excellence, an allegory of the origin of religion. It’s also an exceptionally relaxing film to look at. Observing the participants absorbed like Carthusian monks in their individual tasks, even while working in a group, places the viewer on the same meditative state.

5. Heimat is a Space in Time (Thomas Heise, Germany)

Without question, Heimat is a Space in Time is the best 3½-hour film of the year. Heise’s sprawling experimental documentary uses largely personal documents—letters sent between family members, handed-down private documents—to evoke a broad history of 20th century Germany. As a narrator reads out the exchanges—Heise’s grandfather trying to reason with the Nazi state against his forced retirement, heart-rending accounts from his Jewish great grandparents describing their impending deportation, letters between his parents who were obliged to be in two different places in DDR—we see quotidian images from current day Germany and Austria, urban and rural. For Heise’s family, always made to justify their own place in the country and to never truly belong, the Germanic idea of Heimat seems positively a fantasy. While he reads out his great grandparents’ descriptions of their increasingly impossible conditions of living, Heise presents a scrolling list of Viennese deportees prepared. We try to look for the inevitable arrival of their names in the alphabetical list, our gaze forever deferred. When they do arrive, it feels arbitrary. In other words, what we hear could well be the story of any of the thousand preceding names. Perhaps all of them.

Without question, Heimat is a Space in Time is the best 3½-hour film of the year. Heise’s sprawling experimental documentary uses largely personal documents—letters sent between family members, handed-down private documents—to evoke a broad history of 20th century Germany. As a narrator reads out the exchanges—Heise’s grandfather trying to reason with the Nazi state against his forced retirement, heart-rending accounts from his Jewish great grandparents describing their impending deportation, letters between his parents who were obliged to be in two different places in DDR—we see quotidian images from current day Germany and Austria, urban and rural. For Heise’s family, always made to justify their own place in the country and to never truly belong, the Germanic idea of Heimat seems positively a fantasy. While he reads out his great grandparents’ descriptions of their increasingly impossible conditions of living, Heise presents a scrolling list of Viennese deportees prepared. We try to look for the inevitable arrival of their names in the alphabetical list, our gaze forever deferred. When they do arrive, it feels arbitrary. In other words, what we hear could well be the story of any of the thousand preceding names. Perhaps all of them.

6. Slits (Carlos Segundo, Brazil)

A worthy heir to Tarkovsky’s Solaris, Slits draws its inspiration from quantum physics to explore patently human concerns of loss, grief and memory. The uncertainly principle it offers is a choice between being in this world, awake to the problems of living, and finding meaning in the elsewhere. Physicist Catarina (Roberta Rangel) makes ‘sound-photos’ to study quantum the properties of light. She makes extreme zooms into a digital image to perceive the noise issuing from particular coordinates. These ‘dives’ enable her to listen to conversations from another space-time. Grieving from the loss of her child, Catarina unconsciously attempts to find closure through her research. But trying to inspect the surface of things from too close, she loses sight of her immediate reality; trying to find solace in the objectivity of science, she ends up rediscovering the great lesson of 20th century science (and cinema): that the observer influences the observation. Shot in high-definition digital video, Slits is to this new format what Blow-up was to photography. It locates in the trade-offs of the medium—between details and stability, between richness of palette and noise—visual correlatives to its key idea of quantum uncertainty. A brilliant, sophisticated work of politico-philosophical science fiction.

A worthy heir to Tarkovsky’s Solaris, Slits draws its inspiration from quantum physics to explore patently human concerns of loss, grief and memory. The uncertainly principle it offers is a choice between being in this world, awake to the problems of living, and finding meaning in the elsewhere. Physicist Catarina (Roberta Rangel) makes ‘sound-photos’ to study quantum the properties of light. She makes extreme zooms into a digital image to perceive the noise issuing from particular coordinates. These ‘dives’ enable her to listen to conversations from another space-time. Grieving from the loss of her child, Catarina unconsciously attempts to find closure through her research. But trying to inspect the surface of things from too close, she loses sight of her immediate reality; trying to find solace in the objectivity of science, she ends up rediscovering the great lesson of 20th century science (and cinema): that the observer influences the observation. Shot in high-definition digital video, Slits is to this new format what Blow-up was to photography. It locates in the trade-offs of the medium—between details and stability, between richness of palette and noise—visual correlatives to its key idea of quantum uncertainty. A brilliant, sophisticated work of politico-philosophical science fiction.

7. Little Joe (Jessica Hausner, UK/Austria)

Of all the recent classical Hollywood riffs in mind, none reinvigorates the B-movie tradition as intelligently or potently as Little Joe. Hausner’s modernist creature feature is a monster movie unlike any other: the dangers of the genetically-modified “happiness” plant that biologist Emily (Alice Woodard) develops is exposed early on, and there’s no triumphal reassertion of mankind to counter its menace. What we get instead is a protracted, total submission of individuality to a hegemony of happiness. Little Joe is many things at once: a multi-pronged attack on the wellness industry straight out of Lanthimosverse, the difficulty of being less than happy in an environment that demands you to be constantly upbeat, the fallout of women artists trying to expunge their maternal complexes in their work and of mothers having to lead double lives. Hausner’s camera appears to have a mind of its own, settling on the space between people, which is what the film is about: the culturally mediated relations between individuals. It’s notable that the titular plant reproduces not biologically but culturally. With its terrific score and work on colour, Hausner turns the cheesecake aesthetic of the film against itself. The result is a film of unusual intellectual density and formal frisson.

Of all the recent classical Hollywood riffs in mind, none reinvigorates the B-movie tradition as intelligently or potently as Little Joe. Hausner’s modernist creature feature is a monster movie unlike any other: the dangers of the genetically-modified “happiness” plant that biologist Emily (Alice Woodard) develops is exposed early on, and there’s no triumphal reassertion of mankind to counter its menace. What we get instead is a protracted, total submission of individuality to a hegemony of happiness. Little Joe is many things at once: a multi-pronged attack on the wellness industry straight out of Lanthimosverse, the difficulty of being less than happy in an environment that demands you to be constantly upbeat, the fallout of women artists trying to expunge their maternal complexes in their work and of mothers having to lead double lives. Hausner’s camera appears to have a mind of its own, settling on the space between people, which is what the film is about: the culturally mediated relations between individuals. It’s notable that the titular plant reproduces not biologically but culturally. With its terrific score and work on colour, Hausner turns the cheesecake aesthetic of the film against itself. The result is a film of unusual intellectual density and formal frisson.

8. Status and Terrain (Ute Adamczewski, Germany)

In Status and Terrain, the German obsession with documentation and due process is called to testify to the dialectical process of historical remembrance. Adamczewski’s gently moving camera surveys the length and breath of public spaces in the Saxony region, once a Nazi stronghold, now seemingly anaesthetized under liberal democracy. Official communication, bureaucratic reports and private testimonies read on the voiceover incriminate the buildings and monuments we see on screen, revealing their role in power struggles through the ages. Just as the documents vie for a narrative on the soundtrack, ideologies once thought dead and buried surface to stake their claims on the urban landscape in the present. Adamczewski moves through 80 years of German history non-chronologically, the collage of information pointing to the living, breathing nature of political belief systems. Nazi detention of political opponents in concentration camps, Soviet retribution and blindness to victims of persecution, rise of neo-fascist groups post reunification and the historically indifferent, bulldozing force of current-day neoliberalism play out on the surface of seemingly sedate cities and towns. Status and Terrain is a sober, bracing examination of the manner in which prejudice becomes writ, which in turn becomes history, but also of the way in which this history is contested.

In Status and Terrain, the German obsession with documentation and due process is called to testify to the dialectical process of historical remembrance. Adamczewski’s gently moving camera surveys the length and breath of public spaces in the Saxony region, once a Nazi stronghold, now seemingly anaesthetized under liberal democracy. Official communication, bureaucratic reports and private testimonies read on the voiceover incriminate the buildings and monuments we see on screen, revealing their role in power struggles through the ages. Just as the documents vie for a narrative on the soundtrack, ideologies once thought dead and buried surface to stake their claims on the urban landscape in the present. Adamczewski moves through 80 years of German history non-chronologically, the collage of information pointing to the living, breathing nature of political belief systems. Nazi detention of political opponents in concentration camps, Soviet retribution and blindness to victims of persecution, rise of neo-fascist groups post reunification and the historically indifferent, bulldozing force of current-day neoliberalism play out on the surface of seemingly sedate cities and towns. Status and Terrain is a sober, bracing examination of the manner in which prejudice becomes writ, which in turn becomes history, but also of the way in which this history is contested.

9. Ham on Rye (Tyler Taormina, USA)

The premise is a throwback to the clichés of the eighties: a group of teenagers at a suburban school prepare for their prom night. But in Taormina’s sure-handed treatment, this banal event assumes a spiritual dimension. In the film’s cubist first half, different groups of boys and girls make their way to the restaurant-turned-dance hall, where they will take part in rites of initiation into adulthood and experience something like a religious communion. And then, right after this VHS-ready high, a void descends over the film, turning its raptures into a mourning, not for those who have left this small-town existence but for those left behind: disaffected youth drift about the town or going through robotic social rituals, devoid of magic or warmth. It’s a work evidently deriving from personal experience, but one that’s refracted through a formalist lens. The strength of Ham on Rye is not the depth of its ideas, but the vigour of its prose. Taormina’s manifestly personal style emphasizes the surface of things, the idiosyncratic shot division focuses on gestures and minor physical details to construct scenes, and the eclectic sense of music imposes a global consciousness on a narrative that is otherwise extremely local.

The premise is a throwback to the clichés of the eighties: a group of teenagers at a suburban school prepare for their prom night. But in Taormina’s sure-handed treatment, this banal event assumes a spiritual dimension. In the film’s cubist first half, different groups of boys and girls make their way to the restaurant-turned-dance hall, where they will take part in rites of initiation into adulthood and experience something like a religious communion. And then, right after this VHS-ready high, a void descends over the film, turning its raptures into a mourning, not for those who have left this small-town existence but for those left behind: disaffected youth drift about the town or going through robotic social rituals, devoid of magic or warmth. It’s a work evidently deriving from personal experience, but one that’s refracted through a formalist lens. The strength of Ham on Rye is not the depth of its ideas, but the vigour of its prose. Taormina’s manifestly personal style emphasizes the surface of things, the idiosyncratic shot division focuses on gestures and minor physical details to construct scenes, and the eclectic sense of music imposes a global consciousness on a narrative that is otherwise extremely local.

10. Just Don’t Think I’ll Scream (Frank Beauvais, France)

“Cinephiles are sick people”, said Truffaut. Frank Beauvais agrees. Following his father’s passing and a breakup, Beauvais shut himself up in his house in a trou perdu in Eastern France, and watched over 400 films in a period of seven months. Out of this glut, this sickness that Beauvais calls ‘cinéfolie’, came Just Don’t Think I’ll Scream, a film about looking, made wholly of clips from these 400 movies. Through a rapid, self-aware voiceover, the filmmaker reflects on his self-imposed isolation, his panic attacks, the poverty that prevents him from changing his lifestyle, his complicated feelings towards with political action, the conservatism of those around him and his relationship with his parents. Beauvais’s film is a record of his malady as well as its cure. In its very existence, it demonstrates what anyone sufficiently sickened by cultural gluttony must’ve felt: that the only way to give meaning to the void of indiscriminate consumption is to produce something out of it. Just Don’t Think I’ll Scream is not just a cinephile’s film, filled end to end with references, but the preeminent film about cinephilia, the solipsistic hall of mirrors that Beauvais breaks down and rebuilds inside out.

“Cinephiles are sick people”, said Truffaut. Frank Beauvais agrees. Following his father’s passing and a breakup, Beauvais shut himself up in his house in a trou perdu in Eastern France, and watched over 400 films in a period of seven months. Out of this glut, this sickness that Beauvais calls ‘cinéfolie’, came Just Don’t Think I’ll Scream, a film about looking, made wholly of clips from these 400 movies. Through a rapid, self-aware voiceover, the filmmaker reflects on his self-imposed isolation, his panic attacks, the poverty that prevents him from changing his lifestyle, his complicated feelings towards with political action, the conservatism of those around him and his relationship with his parents. Beauvais’s film is a record of his malady as well as its cure. In its very existence, it demonstrates what anyone sufficiently sickened by cultural gluttony must’ve felt: that the only way to give meaning to the void of indiscriminate consumption is to produce something out of it. Just Don’t Think I’ll Scream is not just a cinephile’s film, filled end to end with references, but the preeminent film about cinephilia, the solipsistic hall of mirrors that Beauvais breaks down and rebuilds inside out.

Special Mention: Gully Boy (Zoya Akhtar, India)

Chan’s diaristic digital work is divided into chapters named after family members and unfurls as a process of piecing together of familial history. Through various confrontational interviews with her mother and father, the filmmaker attempts to understand their failed marriage, her strained relation with her step-father and the violence that has structured them both. Chan’s decision to put her entire life-story on film is a brave gesture, but the film closes upon itself, satisfied to be a melodrama valorizing personal experience over broader frameworks. (Consider, in contrast, the rigorous domestic formalism of Liu Jiayin or the socio-political tapestry of Jia Zhangke’s early work.) Chan misses the forest for the lone tree. Winner of the Adolfas Mekas award of the fest.

Chan’s diaristic digital work is divided into chapters named after family members and unfurls as a process of piecing together of familial history. Through various confrontational interviews with her mother and father, the filmmaker attempts to understand their failed marriage, her strained relation with her step-father and the violence that has structured them both. Chan’s decision to put her entire life-story on film is a brave gesture, but the film closes upon itself, satisfied to be a melodrama valorizing personal experience over broader frameworks. (Consider, in contrast, the rigorous domestic formalism of Liu Jiayin or the socio-political tapestry of Jia Zhangke’s early work.) Chan misses the forest for the lone tree. Winner of the Adolfas Mekas award of the fest. Beep assembles anti-communist propaganda material from the 60s and the 70s commissioned by the South Korean state that was based on the mythologizing of a young boy, Lee Seung-bok, slain by North Korean soldiers. With the unseen, absent boy-hero at its focus, Kim’s film depicts the dialectical manner in which a nation defines itself in relationship to an imagined Other. Kim makes minimal aesthetic intervention into the source material – our relation to it automatically ironic by dint of our very distance from the period it was made in – restricting himself to adding periodic beep sounds to the footage, producing something like a cautionary transmission from another world.

Beep assembles anti-communist propaganda material from the 60s and the 70s commissioned by the South Korean state that was based on the mythologizing of a young boy, Lee Seung-bok, slain by North Korean soldiers. With the unseen, absent boy-hero at its focus, Kim’s film depicts the dialectical manner in which a nation defines itself in relationship to an imagined Other. Kim makes minimal aesthetic intervention into the source material – our relation to it automatically ironic by dint of our very distance from the period it was made in – restricting himself to adding periodic beep sounds to the footage, producing something like a cautionary transmission from another world. Black Sun opens with a composition in deep space presenting a metonym for a country in the process of development: high-rise buildings in the background as a pair of actors in period costumes rehearse a scene in the foreground. In a series of Jia Zhangke-like vignettes of Saigon set in middle-class youth hangouts scored to pop songs and television sounds, interspersed with images of a metamorphosing city, we see the distance that separates art from reality and the middle-class from the changes around it. The film culminates in a complex, home-made long take following the protagonist across her house and out into the terrace, where she dances, presumably to the eponymous song.

Black Sun opens with a composition in deep space presenting a metonym for a country in the process of development: high-rise buildings in the background as a pair of actors in period costumes rehearse a scene in the foreground. In a series of Jia Zhangke-like vignettes of Saigon set in middle-class youth hangouts scored to pop songs and television sounds, interspersed with images of a metamorphosing city, we see the distance that separates art from reality and the middle-class from the changes around it. The film culminates in a complex, home-made long take following the protagonist across her house and out into the terrace, where she dances, presumably to the eponymous song. The most challenging and elusive film of the competition I saw is also the most hypnotic. Cloud Shadow gives us a narrative of sorts in first person about a group of people who go into the woods and dissolve in its elements. The film is obliquely a story of the fascination with cinema, of the trans-individualist communal experience it promises, of the desire to dissolve the limits of one’s body into the images and sounds it offers. With an imagery consisting of sumptuous tints, and nuanced colour gradation and superimpositions, the film enraptures as much as it evades easy intellectual grasp. The one film of the festival that felt most like a half-remembered dream.

The most challenging and elusive film of the competition I saw is also the most hypnotic. Cloud Shadow gives us a narrative of sorts in first person about a group of people who go into the woods and dissolve in its elements. The film is obliquely a story of the fascination with cinema, of the trans-individualist communal experience it promises, of the desire to dissolve the limits of one’s body into the images and sounds it offers. With an imagery consisting of sumptuous tints, and nuanced colour gradation and superimpositions, the film enraptures as much as it evades easy intellectual grasp. The one film of the festival that felt most like a half-remembered dream. Ferri’s teasing, playful Dog, Dear appropriates the filmed record of a Soviet zoological experiment in the 1940s in which scientists impart motor functions to different parts of a dead dog. In the incantatory soundtrack, a woman – presumably the animal’s owner – repeatedly conveys messages to it, with each of them prefaced by the titular term of endearment. Ferri’s film would serve sufficiently as a blunt political allegory about the dysfunction of communism, but I think it’s probably fashioning itself as a metaphysical question: the dog might well be kicking but is he alive? His physical resurrection will not be accompanied by a restoration of consciousness. He will not respond to his master’s voice.

Ferri’s teasing, playful Dog, Dear appropriates the filmed record of a Soviet zoological experiment in the 1940s in which scientists impart motor functions to different parts of a dead dog. In the incantatory soundtrack, a woman – presumably the animal’s owner – repeatedly conveys messages to it, with each of them prefaced by the titular term of endearment. Ferri’s film would serve sufficiently as a blunt political allegory about the dysfunction of communism, but I think it’s probably fashioning itself as a metaphysical question: the dog might well be kicking but is he alive? His physical resurrection will not be accompanied by a restoration of consciousness. He will not respond to his master’s voice. Put together from footage apparently shot over twenty years at a Thai army officer’s residence, Tesprateep’s film shows us four conscripts working in the general’s garden. We witness their camaraderie, their obvious boredom, the empty bravado in entrapping small animals and intimidating each other. The misuse of power by the officer in employing these youth to mow his lawn reflects a broader militaristic hierarchy, as is attested by the youths’ casual violence towards the animals and their brutal torturing of a prisoner. Endless, Nameless recalls Claire Denis in its emphasis on military performativity and Werner Herzog in its juxtaposition of idyllic nature and seething violence, all the while retaining an

Put together from footage apparently shot over twenty years at a Thai army officer’s residence, Tesprateep’s film shows us four conscripts working in the general’s garden. We witness their camaraderie, their obvious boredom, the empty bravado in entrapping small animals and intimidating each other. The misuse of power by the officer in employing these youth to mow his lawn reflects a broader militaristic hierarchy, as is attested by the youths’ casual violence towards the animals and their brutal torturing of a prisoner. Endless, Nameless recalls Claire Denis in its emphasis on military performativity and Werner Herzog in its juxtaposition of idyllic nature and seething violence, all the while retaining an  In Fictitious Force, Widmann incidentally poses himself the age-old challenge of ethnological cinema; how to film the Other without imposing your own worldview on him? The filmmaker smartly takes the Chris Marker route, avoiding explanatory voiceover for the rather physical Hindu ritual he photographs and instead holding it at a slightly mystifying – but never exoticizing – distance. Widmann’s film is about this distance, the chasm between experience and knowledge that prevents the observer from experiencing what the observed is experiencing, however understanding he might be. Fictitious Force’s considered reflexivity carefully circumvents the all-too-common trap of conflating the subjectivities of the photographer and the photographed.

In Fictitious Force, Widmann incidentally poses himself the age-old challenge of ethnological cinema; how to film the Other without imposing your own worldview on him? The filmmaker smartly takes the Chris Marker route, avoiding explanatory voiceover for the rather physical Hindu ritual he photographs and instead holding it at a slightly mystifying – but never exoticizing – distance. Widmann’s film is about this distance, the chasm between experience and knowledge that prevents the observer from experiencing what the observed is experiencing, however understanding he might be. Fictitious Force’s considered reflexivity carefully circumvents the all-too-common trap of conflating the subjectivities of the photographer and the photographed. Fashioned out of footage that the artist shot during his visit to the titular natural reserve in Ontario, Fish Point comes across as an impressionist cine-sketch of the locale. The film opens with Daichi Saito-esque silhouettes of trees against harsh pulsating light – near-monochrome shots that are then superimposed over a slow, green-saturated pan shot of a section of a forest. This segment gives way to a passage with purely geometric compositions consisting of alternating browns and greens and strong horizontals and verticals. Forms change abruptly and tints become more diffuse and earthly. We are finally shown the sea and the horizon, with a rough map of the area overlaid on the imagery.

Fashioned out of footage that the artist shot during his visit to the titular natural reserve in Ontario, Fish Point comes across as an impressionist cine-sketch of the locale. The film opens with Daichi Saito-esque silhouettes of trees against harsh pulsating light – near-monochrome shots that are then superimposed over a slow, green-saturated pan shot of a section of a forest. This segment gives way to a passage with purely geometric compositions consisting of alternating browns and greens and strong horizontals and verticals. Forms change abruptly and tints become more diffuse and earthly. We are finally shown the sea and the horizon, with a rough map of the area overlaid on the imagery. A music video for a song that reportedly riffs on a holy chant and the traditional cry of the local ragman, Ye’s film starts out with shots of old women and men lip-syncing to the titular melody before turning increasingly darker. The rag picker of the poem progresses from accepting material refuse to buying off diseases, emotional traumas and even intolerable human characters. Ye builds the video using shots both documentary and voluntarily-performed that portray everyday life in Taiwan as being poised between tradition and modernity. The junkman of the film then becomes a witness to all that the society rejects and, hence, to all that it stands for.

A music video for a song that reportedly riffs on a holy chant and the traditional cry of the local ragman, Ye’s film starts out with shots of old women and men lip-syncing to the titular melody before turning increasingly darker. The rag picker of the poem progresses from accepting material refuse to buying off diseases, emotional traumas and even intolerable human characters. Ye builds the video using shots both documentary and voluntarily-performed that portray everyday life in Taiwan as being poised between tradition and modernity. The junkman of the film then becomes a witness to all that the society rejects and, hence, to all that it stands for. Set in a suburban Mumbai slum, Bhargava’s film takes a look into one of the reportedly many carrom clubs in the area where young boys come to play, smoke and generally indulge in displays of precocious masculinity. Where Imraan, the 11-year-old manager of the club, seems reticent before the camera, his peers and clients are much more willing to perform adulthood in front of the filming crew. While some of them are acutely aware of the intrusive presence of the camera, urging their friends not to project a bad image of the country, the film itself seems indifferent about the ethics of filming these youngsters, asking them condescending questions with a problematic, non-committal non-judgmentalism.

Set in a suburban Mumbai slum, Bhargava’s film takes a look into one of the reportedly many carrom clubs in the area where young boys come to play, smoke and generally indulge in displays of precocious masculinity. Where Imraan, the 11-year-old manager of the club, seems reticent before the camera, his peers and clients are much more willing to perform adulthood in front of the filming crew. While some of them are acutely aware of the intrusive presence of the camera, urging their friends not to project a bad image of the country, the film itself seems indifferent about the ethics of filming these youngsters, asking them condescending questions with a problematic, non-committal non-judgmentalism. Völter’s visually pleasing and relaxing silent film is a compilation of scientific documents of cloud movement over the Mount Fuji recorded from a static observatory by Japanese physicist Masanao Abe in the 1920s and 1930s. Abe’s problem was also one of cinema’s primary challenges: to study the invisible through the visible; in this case, to examine air currents through cloud patterns. The air currents take numerous different directions and these variegated views of the mountain situate the film in the tradition of Mt. Fuji paintings. The end product is a James Benning-like juxtaposition of fugitive and stable forms, a duet between rapidly changing and unchanging natural entities.

Völter’s visually pleasing and relaxing silent film is a compilation of scientific documents of cloud movement over the Mount Fuji recorded from a static observatory by Japanese physicist Masanao Abe in the 1920s and 1930s. Abe’s problem was also one of cinema’s primary challenges: to study the invisible through the visible; in this case, to examine air currents through cloud patterns. The air currents take numerous different directions and these variegated views of the mountain situate the film in the tradition of Mt. Fuji paintings. The end product is a James Benning-like juxtaposition of fugitive and stable forms, a duet between rapidly changing and unchanging natural entities. The most narrative film of the competition, Memorials situates itself in the tradition of 21st century Slow Cinema with its elliptical exposition, stylized longueurs, (a bit too) naturalistic sound and its overall emphasis on Bazinian realism. A young man revisits his father’s house long after his passing and starts discovering him through the objects of his everyday use, while a dead fish becomes the instrument of meditation and grieving. Though rather conventional in its workings, Memorials offers the details in its interstices fairly subtly and touches upon the usual themes of inter-generational inheritance and posthumous rapprochement, while also gesturing towards a necessary break from the past.

The most narrative film of the competition, Memorials situates itself in the tradition of 21st century Slow Cinema with its elliptical exposition, stylized longueurs, (a bit too) naturalistic sound and its overall emphasis on Bazinian realism. A young man revisits his father’s house long after his passing and starts discovering him through the objects of his everyday use, while a dead fish becomes the instrument of meditation and grieving. Though rather conventional in its workings, Memorials offers the details in its interstices fairly subtly and touches upon the usual themes of inter-generational inheritance and posthumous rapprochement, while also gesturing towards a necessary break from the past. Punprutsachat’s work is a straightforward document of the protracted rescue of a water buffalo from a man-made well on a sultry summer afternoon by dozens of village folk. Shot with a handheld digital camera and employing mostly on-location sound, the film presents to us the efforts of the villagers in chipping away at the edifice, restraining the animal from agitating and finally allowing it to go back to its herd. Natee Cheewit attempts to encapsulate the idea of eternal struggle between man and animal and, more broadly, between nature and civilization. The remnants of the demolished pit and the dog wandering about it are reminders of this sometimes symbiotic, sometimes destructive interaction.

Punprutsachat’s work is a straightforward document of the protracted rescue of a water buffalo from a man-made well on a sultry summer afternoon by dozens of village folk. Shot with a handheld digital camera and employing mostly on-location sound, the film presents to us the efforts of the villagers in chipping away at the edifice, restraining the animal from agitating and finally allowing it to go back to its herd. Natee Cheewit attempts to encapsulate the idea of eternal struggle between man and animal and, more broadly, between nature and civilization. The remnants of the demolished pit and the dog wandering about it are reminders of this sometimes symbiotic, sometimes destructive interaction. Night Watch is reportedly set in the days following the military coup in Thailand in May, 2014 – a period of state repression dissimulated by triumphalist propaganda about reigning happiness. Chulphuthiphong’s debut film showcases one quiet night during this period. Jacques Tati-esque cross-sectional shots of isolated apartments and office spaces show the citizenry complacently cloistered in their domestic and professional spaces, much like the sundry critters that crawl about in the night. Someone surfs through television channels. Most of them are censored, the rest telecast inane entertainment. Night Watch underscores the mundanity and the ordinariness of the whole situation, which is the source of the film’s horror.

Night Watch is reportedly set in the days following the military coup in Thailand in May, 2014 – a period of state repression dissimulated by triumphalist propaganda about reigning happiness. Chulphuthiphong’s debut film showcases one quiet night during this period. Jacques Tati-esque cross-sectional shots of isolated apartments and office spaces show the citizenry complacently cloistered in their domestic and professional spaces, much like the sundry critters that crawl about in the night. Someone surfs through television channels. Most of them are censored, the rest telecast inane entertainment. Night Watch underscores the mundanity and the ordinariness of the whole situation, which is the source of the film’s horror. A rapid editing rhythm approximating the audiovisual assault of the information age, a visual idiom weaving together anime, pencil-drawing and Pink Film aesthetic and a soundscape consisting of reversed audio and noise of clicking mice and shattering glass defines Ouchi’s high-strung portrayal of modern adolescent anxieties. In a progressively sombre, cyclic series of events, a teenager navigates the real and virtual worlds that are haunted by sex and death around her. Ouchi’s pulsating, mutating forms and her preoccupation with the hyper-sexualization of visual culture are reminiscent of

A rapid editing rhythm approximating the audiovisual assault of the information age, a visual idiom weaving together anime, pencil-drawing and Pink Film aesthetic and a soundscape consisting of reversed audio and noise of clicking mice and shattering glass defines Ouchi’s high-strung portrayal of modern adolescent anxieties. In a progressively sombre, cyclic series of events, a teenager navigates the real and virtual worlds that are haunted by sex and death around her. Ouchi’s pulsating, mutating forms and her preoccupation with the hyper-sexualization of visual culture are reminiscent of  One of the high points of the festival, Scrapbook consists of videograms shot in 1967 in a care centre in Ohio for autistic children with commentary by one of the patients, Donna, recorded (and curiously re-performed by a voiceover artist at Donna’s request) in 2014. Donna’s words – indeed, her very use of the pronoun ‘I’ – not only attest to the vast improvement in her personal mental condition, but also throw light on the psychological mechanisms that engender a self-identity. For Donna and the other children-patients filming each other, the act of filming and watching substitutes for their thwarted mirror-stage of psychological development, helping them experience their own individuality, reclaim their bodies. Bracing stuff.

One of the high points of the festival, Scrapbook consists of videograms shot in 1967 in a care centre in Ohio for autistic children with commentary by one of the patients, Donna, recorded (and curiously re-performed by a voiceover artist at Donna’s request) in 2014. Donna’s words – indeed, her very use of the pronoun ‘I’ – not only attest to the vast improvement in her personal mental condition, but also throw light on the psychological mechanisms that engender a self-identity. For Donna and the other children-patients filming each other, the act of filming and watching substitutes for their thwarted mirror-stage of psychological development, helping them experience their own individuality, reclaim their bodies. Bracing stuff. Canadian animator Leslie Supnet’s hand-drawn animation piece is an extension of her previous work

Canadian animator Leslie Supnet’s hand-drawn animation piece is an extension of her previous work  According to the program notes, the project brings together a real-life DJ who has lost her job after the coup d’etat in 2014 and an actual illegal immigrant boy from Myanmar at a secluded pond in the woods to allow them to do what they can’t in real life. We see the DJ perform for the camera, talking with imaginary strangers, giving and playing unheard songs, while the boy is content in tossing stones into the moss-covered pond. Like a structural film, The Asylum, alternates between the DJ’s ‘calls’ and the boy’s quiet alienation, taking occasional albeit unmotivated excursions into impressionist image-making, to weave a vignette about ordinary people made fugitives overnight.

According to the program notes, the project brings together a real-life DJ who has lost her job after the coup d’etat in 2014 and an actual illegal immigrant boy from Myanmar at a secluded pond in the woods to allow them to do what they can’t in real life. We see the DJ perform for the camera, talking with imaginary strangers, giving and playing unheard songs, while the boy is content in tossing stones into the moss-covered pond. Like a structural film, The Asylum, alternates between the DJ’s ‘calls’ and the boy’s quiet alienation, taking occasional albeit unmotivated excursions into impressionist image-making, to weave a vignette about ordinary people made fugitives overnight. A Kiarostami-like narrative minimalism characterizes Radjamuda’s naturalistic sketch in digital monochrome of a lazy holiday afternoon. A young boy perched near the window of his house engages in a series of self-absorbed activities, while actions quotidian and dramatic, including a hinted domestic conflict, wordlessly unfold around him off-screen. A series of shallow-focus shots rally around a wide-angle master shot of the backyard to establish clear spatial relations. Literally and metaphorically set at the boundary between the inside and the outside of the house – home and the world – Radjamuda’s film is a pocket-sized paean to childhood’s privilege of insouciance and to the transformative power of imagination.

A Kiarostami-like narrative minimalism characterizes Radjamuda’s naturalistic sketch in digital monochrome of a lazy holiday afternoon. A young boy perched near the window of his house engages in a series of self-absorbed activities, while actions quotidian and dramatic, including a hinted domestic conflict, wordlessly unfold around him off-screen. A series of shallow-focus shots rally around a wide-angle master shot of the backyard to establish clear spatial relations. Literally and metaphorically set at the boundary between the inside and the outside of the house – home and the world – Radjamuda’s film is a pocket-sized paean to childhood’s privilege of insouciance and to the transformative power of imagination. The shadow of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s work is strongest in Kapadia’s three-part work about the cycles of life, death and reincarnation and the interaction between mankind and nature, between the real and the surreal. Set in various regions of India and in multiple languages and shot predominantly between dusk and dawn, the film has a beguiling though mannered visual quality to it, with its appeal predicated on primal, elemental evocations of the supernatural. While Kapadia’s superimposition of line drawings on shot footage to depict man’s longing for and transformation into nature demands attention, the film itself seems derivative and a bit too enamoured of its influences.

The shadow of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s work is strongest in Kapadia’s three-part work about the cycles of life, death and reincarnation and the interaction between mankind and nature, between the real and the surreal. Set in various regions of India and in multiple languages and shot predominantly between dusk and dawn, the film has a beguiling though mannered visual quality to it, with its appeal predicated on primal, elemental evocations of the supernatural. While Kapadia’s superimposition of line drawings on shot footage to depict man’s longing for and transformation into nature demands attention, the film itself seems derivative and a bit too enamoured of its influences. A potential companion piece to Porumboiu’s

A potential companion piece to Porumboiu’s  At least as formally innovative as Rithy Panh’s

At least as formally innovative as Rithy Panh’s  Wind Castle opens with a complex composition made of an unfinished (or destroyed) building behind a burnt crater, with the moon in full bloom. We are somewhere in the Indian hinterlands, a brick manufacturing site tucked inside large swathes of commercial plantations. Basu’s camera charts the territory in precise, X-axis tracking shots that form a counterpoint to the verticality of the trees. Noise from occasional on-location radios and trucks fill the soundtrack. A surveyor studies the area and trees are marked. ‘Development’ is perhaps around the corner. But the rain gods arrive first. Basu’s quasi-rural-symphony paints an atmospheric picture of quiet lives closer to and at the mercy of nature.

Wind Castle opens with a complex composition made of an unfinished (or destroyed) building behind a burnt crater, with the moon in full bloom. We are somewhere in the Indian hinterlands, a brick manufacturing site tucked inside large swathes of commercial plantations. Basu’s camera charts the territory in precise, X-axis tracking shots that form a counterpoint to the verticality of the trees. Noise from occasional on-location radios and trucks fill the soundtrack. A surveyor studies the area and trees are marked. ‘Development’ is perhaps around the corner. But the rain gods arrive first. Basu’s quasi-rural-symphony paints an atmospheric picture of quiet lives closer to and at the mercy of nature.