2025 was disappointing, even frustrating in both personal and historical terms. At the beginning of the year, I had set myself simple goals, all of which I failed at. My reading plummeted to almost zero, as did my public writing. I had hoped to add more entries to the Curator’s Corner column, but it was not to be. A few projects and opportunities that I was looking forward to didn’t materialize. Not to mention a host of health issues and family emergencies.

The political optimism of 2024 proved not just short lived, but derisory given the impunity with which the lunatics in power and their rabid supporters continued to destroy everything decent, human and life-sustaining. In India, state and market censorship alike have reached absurd levels, awards are now so compromised as to make satirists twiddle their thumbs, festivals are pushed to the brink of dysfunction by a philistine information ministry, naked propaganda seems to be the only way to box-office salvation, critics have been harassed by industry insiders and barbaric hordes on social media for precisely doing their job, celebrities continue to toe the line or silence themselves out of a justified fear of reprisal. All this, just in the domain of cinema.

The only respite for me came in the form of encounters with interesting, reasonable and committed people, especially at the Jakarta Film Week and International Film Festival Kerala, both of which I attended for the first time. The passion and the international camaraderie that I witnessed were welcome assurances that, no matter its immediate currency, bigotry and parochialism will forever be uncool.

In more solitary undertakings, I had the chance to explore parts of Indian documentary history I was unfamiliar with. Among these, I strongly recommend Chalam Bennurkar’s Children of Mini-Japan (1990), Anjali Monteiro and K.P. Jayasankar’s YCP 1997 (1997), David MacDougall’s Doon School Quintet (2000-04), Deepa Dhanraj’s Invoking Justice (2011) and especially R.V. Ramani’s My Camera and Tsunami (2011).

Besides acclaimed and popular films from Kerala made after 2010, I also caught up on a significant swathe of Malayalam cinema from the 80s and the 90s. This included two canonical masterpieces in Perumthachan (1991) and Ponthan Mada (1994) in addition to numerous remarkable features emerging from a short, bountiful period of heightened creativity: Irakal (1985), Deshadanakkili Karayarilla (1986), Thaniyavarthanam (1987), Amrutham Gamaya (1987), Ponmuttayidunna Tharavu (1988), Dasharatham (1989), Varavelpu (1989), Sandhesam (1991), Bharatham (1991) and Njan Gandharvan (1991), to name but a few. Farewell Sreenivasan, the recently departed actor-director-screenwriter behind many of these titles.

As always, the following list is based on an arbitrary eligibility criterion: films that had a world premiere in 2025.

1. Happiness (Firat Yücel, Turkey/Netherlands)

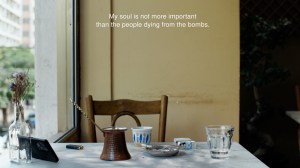

Fatigued and sleep deprived, a Turkish filmmaker in Amsterdam tries to find ways to reduce his excessive screen usage and catch some shuteye. But the horrors of the world, beamed onto digital screens in real time, know no respite. Firat Yücel’s extraordinary desktop essay departs from this premise in all directions, only to return to it with new insights and dizzyingly far-reaching associations. Tracing the agonized drifts of a sensitive, hyperconnected mind, Happiness lays bare a highly contemporary double bind: if the screens we are hooked to keep us away from living in the real world, it is these very screens that helps us make sense of our lived experiences. The filmmaker’s investigation into his bodily malaise leads him to unpack its historical conditions: the colonial legacy that underpins the prosperity of his host country, its flourishing happiness industry and its dubious foreign policies. Yücel’s inward observation takes him ever outward; his exasperation at the immediate present, into the distant past. Rigorous as it is witty and playful, Happiness perfectly embodies the agitations of the modern liberal consciousness, present everywhere and nowhere at once, all too aware of the immensity of human misery as well as its own impotence in the face of it. [World Premiere: Visions du Réel]

Fatigued and sleep deprived, a Turkish filmmaker in Amsterdam tries to find ways to reduce his excessive screen usage and catch some shuteye. But the horrors of the world, beamed onto digital screens in real time, know no respite. Firat Yücel’s extraordinary desktop essay departs from this premise in all directions, only to return to it with new insights and dizzyingly far-reaching associations. Tracing the agonized drifts of a sensitive, hyperconnected mind, Happiness lays bare a highly contemporary double bind: if the screens we are hooked to keep us away from living in the real world, it is these very screens that helps us make sense of our lived experiences. The filmmaker’s investigation into his bodily malaise leads him to unpack its historical conditions: the colonial legacy that underpins the prosperity of his host country, its flourishing happiness industry and its dubious foreign policies. Yücel’s inward observation takes him ever outward; his exasperation at the immediate present, into the distant past. Rigorous as it is witty and playful, Happiness perfectly embodies the agitations of the modern liberal consciousness, present everywhere and nowhere at once, all too aware of the immensity of human misery as well as its own impotence in the face of it. [World Premiere: Visions du Réel]

2. Peter Hujar’s Day (Ira Sachs, USA)

Ira Sachs’ eminently cinematic re-creation of a tape-recorded conversation, from December 1974, between writer Linda Rosenkrantz (played by Rebecca Hall) and photographer Peter Hujar (Ben Whishaw) is an object lesson in the creative possibilities of redundancy, a vital illustration of how the film medium can actualize itself, not by shunning the written word but, on the contrary, by faithfully embracing it. Over 76 condensed minutes, Hujar recollects a day from his life in New York City in rigorous detail — a fascinating mix of the ordinary and the extraordinary, recalling The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975) — to an attentive, sympathetic Rosenkratz amid the changing light of his apartment. As Hujar’s endless stream of speech washes over us to the point of exhaustion, our focus turns from its specific content to the process by which memory becomes material. Drawing from transcripts of the conversation — and not Rosenkrantz’s original recording, now lost —Whishaw’s incredibly textured performance reveals the task of imaginative translation that underlies all actorly work. For all its thrilling verbosity, Sachs’s film is a tribute to the art of listening, to this intimate space of friendship in which the hierarchy between the memorable and the mundane ceases to exist. [WP: Sundance Film Festival]

Ira Sachs’ eminently cinematic re-creation of a tape-recorded conversation, from December 1974, between writer Linda Rosenkrantz (played by Rebecca Hall) and photographer Peter Hujar (Ben Whishaw) is an object lesson in the creative possibilities of redundancy, a vital illustration of how the film medium can actualize itself, not by shunning the written word but, on the contrary, by faithfully embracing it. Over 76 condensed minutes, Hujar recollects a day from his life in New York City in rigorous detail — a fascinating mix of the ordinary and the extraordinary, recalling The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975) — to an attentive, sympathetic Rosenkratz amid the changing light of his apartment. As Hujar’s endless stream of speech washes over us to the point of exhaustion, our focus turns from its specific content to the process by which memory becomes material. Drawing from transcripts of the conversation — and not Rosenkrantz’s original recording, now lost —Whishaw’s incredibly textured performance reveals the task of imaginative translation that underlies all actorly work. For all its thrilling verbosity, Sachs’s film is a tribute to the art of listening, to this intimate space of friendship in which the hierarchy between the memorable and the mundane ceases to exist. [WP: Sundance Film Festival]

3. Manal Issa, 2024 (Elisabeth Subrin, Lebanon/USA)

Where Elisabeth Subrin’s powerful Maria Schneider, 1983 (2022) — based on a televised interview of the eponymous French actress — created doubles, Manal Issa, 2024 proposes a negation. Here, Subrin asks the Lebanese-French actress Manal Issa, one of the three participants of the former film, the same questions that Schneider was posed in the original interview. Vocal about her stances, Issa talks about the poverty of meaningful roles offered to Arab-origin actresses, the limitations of the capitalist production model, the choice of moving back to Lebanon during crisis and the importance of speaking up against political iniquity. She adds that she feels professionally isolated for voicing her opinions, for calling out Israel’s bombing of Gaza. While we listen to her responses, Issa herself remains offscreen, her refusal to sustain her career by censoring herself echoed by Subrin’s refusal to show her. “If I can’t be true to myself, there is no point showing myself,” the actress concludes. Like Schneider’s palpable reluctance, Issa’s self-negation stems from an outlook that privileges life over films, reality over fiction. Six hours after the shoot, an end card notes, “Israeli airstrikes escalated throughout Lebanon, killing over 500 people in one day.” [WP: Cinéma du Réel]

Where Elisabeth Subrin’s powerful Maria Schneider, 1983 (2022) — based on a televised interview of the eponymous French actress — created doubles, Manal Issa, 2024 proposes a negation. Here, Subrin asks the Lebanese-French actress Manal Issa, one of the three participants of the former film, the same questions that Schneider was posed in the original interview. Vocal about her stances, Issa talks about the poverty of meaningful roles offered to Arab-origin actresses, the limitations of the capitalist production model, the choice of moving back to Lebanon during crisis and the importance of speaking up against political iniquity. She adds that she feels professionally isolated for voicing her opinions, for calling out Israel’s bombing of Gaza. While we listen to her responses, Issa herself remains offscreen, her refusal to sustain her career by censoring herself echoed by Subrin’s refusal to show her. “If I can’t be true to myself, there is no point showing myself,” the actress concludes. Like Schneider’s palpable reluctance, Issa’s self-negation stems from an outlook that privileges life over films, reality over fiction. Six hours after the shoot, an end card notes, “Israeli airstrikes escalated throughout Lebanon, killing over 500 people in one day.” [WP: Cinéma du Réel]

4. One Battle After Another (Paul Thomas Anderson, USA)

All appeal is sexual, political appeal especially so. Among other things, Paul Thomas Anderson’s wild, action-filled, hysterically funny ride through a caricatural America torn between white supremacists and antifa insurgents — each more paranoid than the other about imagined contaminations — lays bare the erotic drive animating ideological cohesion (and ideological sabotage). Leonardo DiCaprio’s failed revolutionary, mentally arrested in the 1970s, and Sean Penn’s boyish, waif-like sergeant are twisted projections of each other’s fears. Whether the film is reactionary, apolitical or progressive is beside the point. This is a work by an artist who contemplates a polarized society, its excesses and its mess-ups with sage amusement, or a stoner’s delight, without giving in to cynicism or misanthropy. DiCaprio delivers the performance of the year in a movie filled with performances of the year, each one on a different register, all of it nevertheless brought into perfect harmony by dint of sheer directorial orchestration. One Battle After Another stands tall in a movie culture dominated by safe, anaemic films calculated to say the right things and avoid broaching the wrong things. It made me wish we had more filmmakers who actually felt something between their legs. [WP: international commercial release]

All appeal is sexual, political appeal especially so. Among other things, Paul Thomas Anderson’s wild, action-filled, hysterically funny ride through a caricatural America torn between white supremacists and antifa insurgents — each more paranoid than the other about imagined contaminations — lays bare the erotic drive animating ideological cohesion (and ideological sabotage). Leonardo DiCaprio’s failed revolutionary, mentally arrested in the 1970s, and Sean Penn’s boyish, waif-like sergeant are twisted projections of each other’s fears. Whether the film is reactionary, apolitical or progressive is beside the point. This is a work by an artist who contemplates a polarized society, its excesses and its mess-ups with sage amusement, or a stoner’s delight, without giving in to cynicism or misanthropy. DiCaprio delivers the performance of the year in a movie filled with performances of the year, each one on a different register, all of it nevertheless brought into perfect harmony by dint of sheer directorial orchestration. One Battle After Another stands tall in a movie culture dominated by safe, anaemic films calculated to say the right things and avoid broaching the wrong things. It made me wish we had more filmmakers who actually felt something between their legs. [WP: international commercial release]

5. Beyond the Mast (Mohammad Nuruzzaman, Bangladesh)

In this rapturous slice-of-life portrait, a small commercial boat with an all-male crew goes from port to port along a river in Bangladesh selling oil. When the crew’s kindly cook takes a stowaway child under his aegis, he runs afoul of the boat’s ill-tempered, scheming helmsman, covetous of the captain’s job. Despite a good deal of on-board intrigue, there is very little drama, strictly speaking, in Mohammad Nuruzzaman’s artisanal second feature, which doesn’t even seek to create lyrical moments in the vein of, say, Satyajit Ray. Yet, this is a highly poetic work, the poetry arising primarily from the filmmaker’s intent, non-judgmental way of looking at a small, enclosed world, its rituals, its diverse people and their human foibles: touches of jealousy, compassion, malevolence, ambition and camaraderie; a parade of life simply passing by. The form is meditative yet brisk — with very elegant camera choreography — and remains indifferent to fashionable arthouse formulas, stylistic shorthand or established screenplay structures. Even the film’s casual neo-realism doesn’t aim at traditional qualities of empathy and psychological description; it rather inspires Ozu-like contemplation. Just a lovingly crafted film. [WP: Moscow International Film Festival]

In this rapturous slice-of-life portrait, a small commercial boat with an all-male crew goes from port to port along a river in Bangladesh selling oil. When the crew’s kindly cook takes a stowaway child under his aegis, he runs afoul of the boat’s ill-tempered, scheming helmsman, covetous of the captain’s job. Despite a good deal of on-board intrigue, there is very little drama, strictly speaking, in Mohammad Nuruzzaman’s artisanal second feature, which doesn’t even seek to create lyrical moments in the vein of, say, Satyajit Ray. Yet, this is a highly poetic work, the poetry arising primarily from the filmmaker’s intent, non-judgmental way of looking at a small, enclosed world, its rituals, its diverse people and their human foibles: touches of jealousy, compassion, malevolence, ambition and camaraderie; a parade of life simply passing by. The form is meditative yet brisk — with very elegant camera choreography — and remains indifferent to fashionable arthouse formulas, stylistic shorthand or established screenplay structures. Even the film’s casual neo-realism doesn’t aim at traditional qualities of empathy and psychological description; it rather inspires Ozu-like contemplation. Just a lovingly crafted film. [WP: Moscow International Film Festival]

6. Roohrangi (Tusharr Madhavv, India/Netherlands)

With a camera in hand, a gay filmmaker from South Asia walks around in a park in Amsterdam known as a cruising hotspot. What he finds in this place of fleeting encounters is a kind of time warp, the apparent permanence of its majestic trees, their gnarled roots and variegated textures reminding him of his own roots back in Lucknow, India. They recall, in particular, his grandfather’s discoloured skin, caused by leukoderma, which made him look like a white man — a dual identity paralleling the filmmaker’s own. Echoing this image, Roohrangi starts to lose its colours too, shedding its skin to reveal various layers of memory, history and fantasy underlying a leisurely stroll, as different geographies and eras interpenetrate one another. Like in the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, the forest in Roohrangi is a liminal, essentially queer space that enables communion with other lives, other worlds — a glimpse into different possibilities of being. With curiosity and formal openness, Tusharr Madhavv mixes stylized, essayistic passages with casual interviews with the park’s denizens. The result is an evocative, visually striking work, at once experimental and accessible, that achieves the right balance of discursivity, mystery and invention. [WP: Ann Arbor Film Festival]

With a camera in hand, a gay filmmaker from South Asia walks around in a park in Amsterdam known as a cruising hotspot. What he finds in this place of fleeting encounters is a kind of time warp, the apparent permanence of its majestic trees, their gnarled roots and variegated textures reminding him of his own roots back in Lucknow, India. They recall, in particular, his grandfather’s discoloured skin, caused by leukoderma, which made him look like a white man — a dual identity paralleling the filmmaker’s own. Echoing this image, Roohrangi starts to lose its colours too, shedding its skin to reveal various layers of memory, history and fantasy underlying a leisurely stroll, as different geographies and eras interpenetrate one another. Like in the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, the forest in Roohrangi is a liminal, essentially queer space that enables communion with other lives, other worlds — a glimpse into different possibilities of being. With curiosity and formal openness, Tusharr Madhavv mixes stylized, essayistic passages with casual interviews with the park’s denizens. The result is an evocative, visually striking work, at once experimental and accessible, that achieves the right balance of discursivity, mystery and invention. [WP: Ann Arbor Film Festival]

7. Past Is Present (Shaheen Dill-Riaz, Germany/Bangladesh)

In 2007, Berlin-based Bangladeshi documentarian Shaheen Dill-Riaz found himself in the midst of a family scandal: while studying abroad, his sister Mitul had secretly married her cousin to the great chagrin of her parents. As this taboo union began to tear the family apart, Dill-Riaz decided to mediate between Mitul in Australia, his elder brother Amirul in the USA and his heartbroken parents back home in Dhaka. In Past Is Present, Dill-Riaz turns his camera onto himself and his dear ones, producing a sweeping domestic saga shot over fourteen years and across four continents. Tracing his parents’ journey from rural Bangladesh to Dhaka, and their three children’s subsequent drift to far-flung corners of the globe, the filmmaker examines the complex personal fallout of voluntary migration, presented here in all its liberating and melancholic dimensions. Dill-Riaz seamlessly interweaves moments of torrid drama with passages of mundane poetry, his handheld camera adopting a transparent, unassuming style. The film’s international narrative produces a startling contrast of textures and lifestyles, but also crystallizes the profound continuities in emotional and moral values across cultures. A touching study in the tyranny of distance, Past Is Present actualizes the immortal struggle between the home and the world. [WP: International Film Festival Rotterdam]

8. Obscure Night – Ain’t I a Child? (Sylvain George, France)

The concluding chapter of Sylvain George’s trilogy on illegal immigration is an extraordinary object of close, unflinching observation. The film follows three Tunisian teenagers who take temporary refuge in Paris after having been shuttled by immigration authorities across various cities in Western Europe. With remarkable intimacy and equanimity, George’s camera films the gang at slightly below the eye-level as they wander the roads of night-time Paris, huddle around fire, get into nasty fights with their Algerian counterparts, listen to street music or make the occasional phone call back home. An indifferent Eiffel Tower glitters perpetually in the background as the boys find themselves prisoners under an open sky. Shot in stark monochrome with eye-popping passages of abstraction, George’s film lends a monumental weight to images and lives we would rather not see. As a white artist making films on vulnerable sans papiers, George is bound to ruffle some feathers. But his film demonstrates that, sometimes, you need to strain certain ethical boundaries to arrive at newer forms of looking and understanding. Neither incriminating its subjects nor making any apology for them, Obscure Night – “Ain’t I a Child?” reveals the herculean difficulty of creating a truly humanist work. [WP: Visions du Réel]

The concluding chapter of Sylvain George’s trilogy on illegal immigration is an extraordinary object of close, unflinching observation. The film follows three Tunisian teenagers who take temporary refuge in Paris after having been shuttled by immigration authorities across various cities in Western Europe. With remarkable intimacy and equanimity, George’s camera films the gang at slightly below the eye-level as they wander the roads of night-time Paris, huddle around fire, get into nasty fights with their Algerian counterparts, listen to street music or make the occasional phone call back home. An indifferent Eiffel Tower glitters perpetually in the background as the boys find themselves prisoners under an open sky. Shot in stark monochrome with eye-popping passages of abstraction, George’s film lends a monumental weight to images and lives we would rather not see. As a white artist making films on vulnerable sans papiers, George is bound to ruffle some feathers. But his film demonstrates that, sometimes, you need to strain certain ethical boundaries to arrive at newer forms of looking and understanding. Neither incriminating its subjects nor making any apology for them, Obscure Night – “Ain’t I a Child?” reveals the herculean difficulty of creating a truly humanist work. [WP: Visions du Réel]

9. May the Soil Be Everywhere (Yehui Zhao, China/USA)

Yehui Zhao’s winsome debut feature begins as a personal documentary about the filmmaker’s search for her roots, but it gradually blooms into a sprawling examination of Chinese society and its evolving relationship to the land across modes of production. In her quest to unearth her family tree, the filmmaker finds herself peeling back layers upon layers of violent history — an excavation that takes her back to the soil, to a primordial ecology: caves that have now become sand mines, dogs that were once wolves, high-speed rail that now cut through unmarked graves. May the Soil Be Everywhere offers a rare and unusual glimpse into China’s pre-revolutionary past that takes us across vastly different terrains, time periods, generations: we learn of landlords who, during the revolution, became persecuted cave dwellers who then turned into Stakhanovite foot soldiers of Mao and are now digital filmmakers in a globalized world. The film’s direct and unaffected voiceover enables the overdone format of the personal documentary to break loose into a free-form essay featuring humorous animation and re-enacted tableaux. If the filmmaker’s attachment to familial lineage feels a little excessive, it undeniably carries a subversive force within post-revolutionary Chinese society. [WP: True/False Film Fest]

Yehui Zhao’s winsome debut feature begins as a personal documentary about the filmmaker’s search for her roots, but it gradually blooms into a sprawling examination of Chinese society and its evolving relationship to the land across modes of production. In her quest to unearth her family tree, the filmmaker finds herself peeling back layers upon layers of violent history — an excavation that takes her back to the soil, to a primordial ecology: caves that have now become sand mines, dogs that were once wolves, high-speed rail that now cut through unmarked graves. May the Soil Be Everywhere offers a rare and unusual glimpse into China’s pre-revolutionary past that takes us across vastly different terrains, time periods, generations: we learn of landlords who, during the revolution, became persecuted cave dwellers who then turned into Stakhanovite foot soldiers of Mao and are now digital filmmakers in a globalized world. The film’s direct and unaffected voiceover enables the overdone format of the personal documentary to break loose into a free-form essay featuring humorous animation and re-enacted tableaux. If the filmmaker’s attachment to familial lineage feels a little excessive, it undeniably carries a subversive force within post-revolutionary Chinese society. [WP: True/False Film Fest]

10. Admission (Quentin Hsu, Taiwan)

Panicked by the rejection of their six-year-old ward at an elite boarding school, an affluent tiger couple convenes an emergency meeting with their “fixer” and one of the school’s board members at a resort. Emerging from their negotiations and blame games is a stark portrait of a childhood labouring under someone else’s dreams. Quentin Hsu’s razor-sharp debut is a formalist kammerspiel that is Mungiu/Farhadi-like in its dissection of the moral corruption of the Chinese middle-class. But the approach to the material is entirely anti-naturalistic, pointedly theatrical. The film makes phenomenal use of its 4:3 aspect ratio and off-screen space, with the masquerade and subterfuge of the dramatic situation reflected in actors constantly gliding in and out of the frame, their bodies now eclipsed by the décor, now irrupting into the shot. The frame is constantly energized and de-energized by these microscopically choreographed movements in a way that recalls the Zürcher brothers. The actors are little more than props in the director’s precise, Kubrick-like design, but it’s bracing to witness a work that articulates its ideas through brute mise en scène, especially for a subject that would have called for a more psycho-realist treatment. [WP: Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival]

Panicked by the rejection of their six-year-old ward at an elite boarding school, an affluent tiger couple convenes an emergency meeting with their “fixer” and one of the school’s board members at a resort. Emerging from their negotiations and blame games is a stark portrait of a childhood labouring under someone else’s dreams. Quentin Hsu’s razor-sharp debut is a formalist kammerspiel that is Mungiu/Farhadi-like in its dissection of the moral corruption of the Chinese middle-class. But the approach to the material is entirely anti-naturalistic, pointedly theatrical. The film makes phenomenal use of its 4:3 aspect ratio and off-screen space, with the masquerade and subterfuge of the dramatic situation reflected in actors constantly gliding in and out of the frame, their bodies now eclipsed by the décor, now irrupting into the shot. The frame is constantly energized and de-energized by these microscopically choreographed movements in a way that recalls the Zürcher brothers. The actors are little more than props in the director’s precise, Kubrick-like design, but it’s bracing to witness a work that articulates its ideas through brute mise en scène, especially for a subject that would have called for a more psycho-realist treatment. [WP: Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival]

Special Mention: Living the Land (Huo Meng, China)

Favourite Films of

2024 • 2023 • 2022 • 2021 • 2020 • 2019

2015 • 2014 • 2013 • 2012 • 2011 • 2010 • 2009

What comprises the blight of modern life? The reverse shot, answers Bruno Dumont in his scorching new dramedy about celebrity news reporter France, played by a dazzling Léa Seydoux, who cannot help but make it about herself in every story she does. Fresh off two films on

What comprises the blight of modern life? The reverse shot, answers Bruno Dumont in his scorching new dramedy about celebrity news reporter France, played by a dazzling Léa Seydoux, who cannot help but make it about herself in every story she does. Fresh off two films on  An apartment evermore waiting to be occupied, letters responding to inquiries not heard, a voice never embodied in the image: Pereda’s five-minute short is a haunting, haunted tribute to the late Chantal Akerman that is structured around absence and substitution. We hear Pereda replying to fictitious queries by the Belgian filmmaker about renting out his sister’s apartment in Mexico City, and we see his sister readying the apartment, moving out paintings or clearing foliage from the skylight. In the film’s robust organization, Pereda, his sister and Akerman become mediums, connecting links in each other’s (after)lives: Pereda, unseen, serving as a middleman between the apartment owner and the impossible future tenant; his sister, unheard, taking the place of Akerman who will never feature in Pereda’s film; and Akerman herself, unseen and unheard, bringing the siblings together in a non-existent real estate deal. In an act of respect and love, Dear Chantal creates a physical space for Akerman to continue to exist, even if not in flesh and blood, just as

An apartment evermore waiting to be occupied, letters responding to inquiries not heard, a voice never embodied in the image: Pereda’s five-minute short is a haunting, haunted tribute to the late Chantal Akerman that is structured around absence and substitution. We hear Pereda replying to fictitious queries by the Belgian filmmaker about renting out his sister’s apartment in Mexico City, and we see his sister readying the apartment, moving out paintings or clearing foliage from the skylight. In the film’s robust organization, Pereda, his sister and Akerman become mediums, connecting links in each other’s (after)lives: Pereda, unseen, serving as a middleman between the apartment owner and the impossible future tenant; his sister, unheard, taking the place of Akerman who will never feature in Pereda’s film; and Akerman herself, unseen and unheard, bringing the siblings together in a non-existent real estate deal. In an act of respect and love, Dear Chantal creates a physical space for Akerman to continue to exist, even if not in flesh and blood, just as  How would Lubitsch do it? Well, if the old master were a contemporary filmmaker, ‘it’ would probably resemble Koberidze’s off-kilter, disarming romantic comedy about two lovers-to-be who work at a shop around the corner without recognizing each other all summer. What Do We See is obviously designed to please, but there is never a sense that it panders to its audience. Like the best storytellers, Koberidze knows that pleasure can be deepened by deferring gratification, and to this end, his film takes surprising excursions away from its central story, restarting at will and relegating its lead couple to the margin as though reposing faith in destiny to bring them together. This vast negative space of the narrative clarifies the larger objective of the film, which is to integrate its characters into the landscape of the ancient town of Kutuisi, whose faces and places, ebbs and flows, become the central subject. Pinning down the fable-like story on the voiceover allows the director to employ a complex, highly unusual visual syntax—that nevertheless derives from classical Hollywood cinema—without disorienting the viewer. The film involves magic, but Koberidze demonstrates that a towel flying through the frame can be as enrapturing as the most outlandish fairy tales.

How would Lubitsch do it? Well, if the old master were a contemporary filmmaker, ‘it’ would probably resemble Koberidze’s off-kilter, disarming romantic comedy about two lovers-to-be who work at a shop around the corner without recognizing each other all summer. What Do We See is obviously designed to please, but there is never a sense that it panders to its audience. Like the best storytellers, Koberidze knows that pleasure can be deepened by deferring gratification, and to this end, his film takes surprising excursions away from its central story, restarting at will and relegating its lead couple to the margin as though reposing faith in destiny to bring them together. This vast negative space of the narrative clarifies the larger objective of the film, which is to integrate its characters into the landscape of the ancient town of Kutuisi, whose faces and places, ebbs and flows, become the central subject. Pinning down the fable-like story on the voiceover allows the director to employ a complex, highly unusual visual syntax—that nevertheless derives from classical Hollywood cinema—without disorienting the viewer. The film involves magic, but Koberidze demonstrates that a towel flying through the frame can be as enrapturing as the most outlandish fairy tales. The title says it all. Loznitsa’s new documentary represents a modulation of style for the filmmaker. Where his found footage work so far dropped the viewer into specific historical events in medias res, without much preparation, Babi Yar. Context offers a broader picture. With the help of archival material, but also uncharacteristic intertitles, the film details the events leading up to, and following, the Babi Yar Massacre of September 1941, where over 33,000 Jews were killed over two days in the eponymous ravine in Kiev. We see Ukrainian citizens welcoming the occupying Nazi forces with enthusiasm and collaborating in the persecution of their Jewish compatriots. In an illustration of the failure of archival, the massacre itself isn’t represented except in photographs of its aftermath. Loznitsa’s shocking film is a rousing J’accuse! directed at his nation, at the willingness of its citizens in enabling genocide, at the amnesia that allowed for the valley to be turned into an industrial dumping ground. Loznitsa’s newfound desire to contextualize his material should be construed less as a loss of faith in images to speak ‘for themselves’ than as a critical acknowledgement of their power to deceive. After all, the Red Army is welcomed with comparable pomp after they liberate Kiev, this formal continuity with the reception of the Nazis concealing a crisis of content.

The title says it all. Loznitsa’s new documentary represents a modulation of style for the filmmaker. Where his found footage work so far dropped the viewer into specific historical events in medias res, without much preparation, Babi Yar. Context offers a broader picture. With the help of archival material, but also uncharacteristic intertitles, the film details the events leading up to, and following, the Babi Yar Massacre of September 1941, where over 33,000 Jews were killed over two days in the eponymous ravine in Kiev. We see Ukrainian citizens welcoming the occupying Nazi forces with enthusiasm and collaborating in the persecution of their Jewish compatriots. In an illustration of the failure of archival, the massacre itself isn’t represented except in photographs of its aftermath. Loznitsa’s shocking film is a rousing J’accuse! directed at his nation, at the willingness of its citizens in enabling genocide, at the amnesia that allowed for the valley to be turned into an industrial dumping ground. Loznitsa’s newfound desire to contextualize his material should be construed less as a loss of faith in images to speak ‘for themselves’ than as a critical acknowledgement of their power to deceive. After all, the Red Army is welcomed with comparable pomp after they liberate Kiev, this formal continuity with the reception of the Nazis concealing a crisis of content. The spectre of Harun Farocki hovers over Herdies and Götmark’s excellent documentary about war, technology and the production of images. A meditation on Western attitudes to armed conflict, Bellum unfolds as an anthology of three human interest stories: a Swedish engineer involved in designing an AI-powered military drone that will take autonomous decisions on bombing a perceived target, a war veteran in Nevada suffering from PTSD and having trouble reintegrating into civilian life, a photojournalist from the East Coast who covers the aftermath of the Afghan war. Well-meaning though these individuals might be, their lives and work are marked by a certain guilt surrounding the fact of war. This is evident in the case of the vet, but the photographer’s own activity may not be untouched by a liberal sense of culpability about her country’s interventions in Afghanistan. The engineer’s efforts to bypass the human factor of war, too, is an attempt to eradicate feelings of guilt about liquidating an enemy, which, the film’s narrator notes, is the only real restraining force in armed conflict. Bellum cogently points out the ways in which technology—of training, of intervention—increasingly eliminates human fallibility from the equation of war, for as Colonel Kurtz put it, “it’s judgment that defeats us.”

The spectre of Harun Farocki hovers over Herdies and Götmark’s excellent documentary about war, technology and the production of images. A meditation on Western attitudes to armed conflict, Bellum unfolds as an anthology of three human interest stories: a Swedish engineer involved in designing an AI-powered military drone that will take autonomous decisions on bombing a perceived target, a war veteran in Nevada suffering from PTSD and having trouble reintegrating into civilian life, a photojournalist from the East Coast who covers the aftermath of the Afghan war. Well-meaning though these individuals might be, their lives and work are marked by a certain guilt surrounding the fact of war. This is evident in the case of the vet, but the photographer’s own activity may not be untouched by a liberal sense of culpability about her country’s interventions in Afghanistan. The engineer’s efforts to bypass the human factor of war, too, is an attempt to eradicate feelings of guilt about liquidating an enemy, which, the film’s narrator notes, is the only real restraining force in armed conflict. Bellum cogently points out the ways in which technology—of training, of intervention—increasingly eliminates human fallibility from the equation of war, for as Colonel Kurtz put it, “it’s judgment that defeats us.” I don’t know if Bruno Dumont and Paul Schrader saw each other’s films this year, but I’m certain they would both have much to say to one another. If

I don’t know if Bruno Dumont and Paul Schrader saw each other’s films this year, but I’m certain they would both have much to say to one another. If  Even if we are done with the 20th century, suggests Sīmanis’ singular, absurd period comedy, the 20th century isn’t yet done with us. When Hans, an opportunistic doorman at a Riga hotel, is falsely implicated in a bombing, he flees the Latvian capital to shuttle from one European city to another. The Europe of 1913 that Hans traverses is less a real geography than an abstract zone of competing political currents. War is around the corner, and there are several groups trying to influence the course of history. Zealous ideologues seek to entice and co-opt him, subjecting him to what Louis Althusser called “interpellation.” All through, Hans fights hard to follow his own moral compass, flee subjecthood and retain his individuality. A historical picaresque, Sīmanis’ film is interested in the singularity of this particular juncture in Western history—a point at which fin de siècle optimism about technology and human rationality came crashing against the reality of trench warfare—where countless isms sought to impose their own vision on the world. It would seem that Sīmanis views Latvia of the early 20th century as something of an ideological waystation, an unstable intellectual field where free radicals like Hans couldn’t help but be neutralized. And that vision isn’t without contemporary resonance.

Even if we are done with the 20th century, suggests Sīmanis’ singular, absurd period comedy, the 20th century isn’t yet done with us. When Hans, an opportunistic doorman at a Riga hotel, is falsely implicated in a bombing, he flees the Latvian capital to shuttle from one European city to another. The Europe of 1913 that Hans traverses is less a real geography than an abstract zone of competing political currents. War is around the corner, and there are several groups trying to influence the course of history. Zealous ideologues seek to entice and co-opt him, subjecting him to what Louis Althusser called “interpellation.” All through, Hans fights hard to follow his own moral compass, flee subjecthood and retain his individuality. A historical picaresque, Sīmanis’ film is interested in the singularity of this particular juncture in Western history—a point at which fin de siècle optimism about technology and human rationality came crashing against the reality of trench warfare—where countless isms sought to impose their own vision on the world. It would seem that Sīmanis views Latvia of the early 20th century as something of an ideological waystation, an unstable intellectual field where free radicals like Hans couldn’t help but be neutralized. And that vision isn’t without contemporary resonance. Maria Speth’s expansive documentary about a batch of preteen students, mostly of an immigrant background, in a public school in Stadtallendorf, Hessen, is a classroom film that achieves something special. Remaining with the children for almost its entire four-hour runtime allows it to individuate them, to look at them as independent beings with their own skills, desires and prejudices, just as their charismatic teacher-guide-philosopher Dieter Bachmann adopts a different approach to each of his pupils. For Bachmann, it would seem, whatever the students accomplish academically during the year is of secondary importance. He knows that he is dealing with a group with an inchoate sense of self: first as pre-adolescents, then as new immigrants. Consequently, he spends a great deal of effort in giving them a sense of community, creating a space where they can be themselves. At the same time, the classroom is a social laboratory where new ideas are introduced and the children brought to interrogate received opinion, all under Bachmann’s paternal authority. Speth insists on the particularity of these individuals and there is no sense that our star teacher is indicative of the schooling system in Germany at large. Bachmann is an exception, and in his exceptionalism lies a promise, a glimpse of how things could be.

Maria Speth’s expansive documentary about a batch of preteen students, mostly of an immigrant background, in a public school in Stadtallendorf, Hessen, is a classroom film that achieves something special. Remaining with the children for almost its entire four-hour runtime allows it to individuate them, to look at them as independent beings with their own skills, desires and prejudices, just as their charismatic teacher-guide-philosopher Dieter Bachmann adopts a different approach to each of his pupils. For Bachmann, it would seem, whatever the students accomplish academically during the year is of secondary importance. He knows that he is dealing with a group with an inchoate sense of self: first as pre-adolescents, then as new immigrants. Consequently, he spends a great deal of effort in giving them a sense of community, creating a space where they can be themselves. At the same time, the classroom is a social laboratory where new ideas are introduced and the children brought to interrogate received opinion, all under Bachmann’s paternal authority. Speth insists on the particularity of these individuals and there is no sense that our star teacher is indicative of the schooling system in Germany at large. Bachmann is an exception, and in his exceptionalism lies a promise, a glimpse of how things could be. It’s an ingenious, wholly cinematic premise: estranged from family and friends, a sound engineer spends her nights at her film studio until she starts to experience a lag between what she sees and what she hears. Juanjo Giménez’s absorbing psychological thriller riffs on this setup, weaving its implications into a coherent character study of a young woman out of sync with her life. The result contains some very amusing set pieces constructed around the delay between sound and image, but also one of the most sublime romantic scenes of all time, one that begins with rude abandonment and ends at a silent movie show. Marta Nieto is brilliant as the unnamed protagonist who withdraws into a shell and then reconnects with herself and the world. She brings a fierce independence to the character that nuances its vulnerability. Its claustrophobic premise notwithstanding, Out of Sync feels like a very open work, integrated gracefully with the urban landscape of beautiful Barcelona. Watching the film in 2021, when so much of real-world interaction has been rendered into digital images and sounds, using Bluetooth speakers with their own latency to boot, is an uncanny experience.

It’s an ingenious, wholly cinematic premise: estranged from family and friends, a sound engineer spends her nights at her film studio until she starts to experience a lag between what she sees and what she hears. Juanjo Giménez’s absorbing psychological thriller riffs on this setup, weaving its implications into a coherent character study of a young woman out of sync with her life. The result contains some very amusing set pieces constructed around the delay between sound and image, but also one of the most sublime romantic scenes of all time, one that begins with rude abandonment and ends at a silent movie show. Marta Nieto is brilliant as the unnamed protagonist who withdraws into a shell and then reconnects with herself and the world. She brings a fierce independence to the character that nuances its vulnerability. Its claustrophobic premise notwithstanding, Out of Sync feels like a very open work, integrated gracefully with the urban landscape of beautiful Barcelona. Watching the film in 2021, when so much of real-world interaction has been rendered into digital images and sounds, using Bluetooth speakers with their own latency to boot, is an uncanny experience. Ambitious to a fault, American artist Jordan Lord’s new work is nearly unwatchable. Yet it bends the documentary form like few films this year. Shared Resources is a home movie made over a considerable period of time, presented in scrambled chronology. We learn that Lord’s father was a debt collector fired by his bank, that his health is deteriorating due to diabetes, that the family lost most of its possessions in the Hurricane Katrina and that they had to declare bankruptcy shortly after Lord’s acceptance into Columbia University. All this material is, however, offered not directly but with a voiceover by Lord and his parents describing the footage we see, as though intended for the visually challenged, and two sets of subtitles, colour-coded for diegetic and non-diegetic speech, seemingly oriented towards the hearing disabled. In having his parents comment on images from rather difficult episodes in their lives, the filmmaker gives them a power over what is represented. Through all this, Lord initiates an exploration of debt in all its forms and shapes: paternal debt towards children, filial debt towards parents, the debt of a documentary filmmaker towards their subjects, one’s debt to their own body, the fuzzy line between love and indebtedness. This is an American film with an Asian sensibility.

Ambitious to a fault, American artist Jordan Lord’s new work is nearly unwatchable. Yet it bends the documentary form like few films this year. Shared Resources is a home movie made over a considerable period of time, presented in scrambled chronology. We learn that Lord’s father was a debt collector fired by his bank, that his health is deteriorating due to diabetes, that the family lost most of its possessions in the Hurricane Katrina and that they had to declare bankruptcy shortly after Lord’s acceptance into Columbia University. All this material is, however, offered not directly but with a voiceover by Lord and his parents describing the footage we see, as though intended for the visually challenged, and two sets of subtitles, colour-coded for diegetic and non-diegetic speech, seemingly oriented towards the hearing disabled. In having his parents comment on images from rather difficult episodes in their lives, the filmmaker gives them a power over what is represented. Through all this, Lord initiates an exploration of debt in all its forms and shapes: paternal debt towards children, filial debt towards parents, the debt of a documentary filmmaker towards their subjects, one’s debt to their own body, the fuzzy line between love and indebtedness. This is an American film with an Asian sensibility.

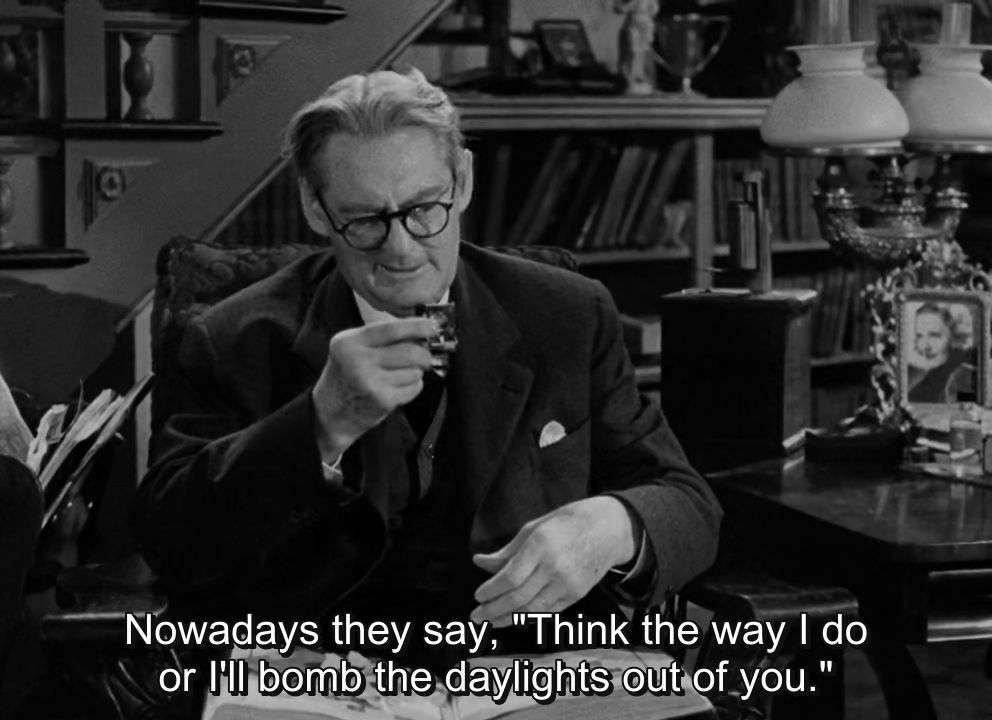

I’ve had no greater screen delight this year than watching two white dudes chat for two hours. Orson Welles and Dennis Hopper hole up in a dark room with half a dozen technicians to talk filmmaking, politics, religion, love, magic, news, television and literature while dutiful assistants scurry about readying one refill of liquor for them after another. Welles plays the Grand Inquisitor, pressing his timid interlocutor to state his artistic and political beliefs, conjuring theories to counter him and never allowing him a resting ground. We never see him, save for rare glimpses of his bellowing pin-striped trousers moving at the edge of the frame. As Hopper’s cinematic forefather, Welles looms large, appearing to be incarnating some kind of metaphysical force, orchestrating a Kafkaesque trial for the young man. What results is a stark power imbalance between the seen and the unseen, the subject and the author, the one who is recorded and the one who wields the camera. But the primary pleasure of the film lies in seeing two artists in a terribly absorbing conversation, grappling with the cinematic-aesthetic problems of their time. Going public after fifty years, Hopper/Welles is both a standalone film and an anniversary celebration. It hasn’t dated one bit.

I’ve had no greater screen delight this year than watching two white dudes chat for two hours. Orson Welles and Dennis Hopper hole up in a dark room with half a dozen technicians to talk filmmaking, politics, religion, love, magic, news, television and literature while dutiful assistants scurry about readying one refill of liquor for them after another. Welles plays the Grand Inquisitor, pressing his timid interlocutor to state his artistic and political beliefs, conjuring theories to counter him and never allowing him a resting ground. We never see him, save for rare glimpses of his bellowing pin-striped trousers moving at the edge of the frame. As Hopper’s cinematic forefather, Welles looms large, appearing to be incarnating some kind of metaphysical force, orchestrating a Kafkaesque trial for the young man. What results is a stark power imbalance between the seen and the unseen, the subject and the author, the one who is recorded and the one who wields the camera. But the primary pleasure of the film lies in seeing two artists in a terribly absorbing conversation, grappling with the cinematic-aesthetic problems of their time. Going public after fifty years, Hopper/Welles is both a standalone film and an anniversary celebration. It hasn’t dated one bit. Chloé Galibert-Laîné’s funny, sharp and dizzyingly smart video work begins as a commentary on Chris Kennedy’s Watching the Detectives (2017), a desktop film about the crowd-sourced investigation on Reddit following the Boston bombing of 2013. As the director breaks down Kennedy’s film, analysing its narrative construction and its tendency for geometric abstraction, she voluntarily gets caught in an ‘analytical frenzy’, not unlike the Redditors themselves. As Galibert-Laîné seamlessly chains one stream of thought after another, her film evolves into a meta-reflection on our relation to images and our compulsion to create meaning from visual material. If

Chloé Galibert-Laîné’s funny, sharp and dizzyingly smart video work begins as a commentary on Chris Kennedy’s Watching the Detectives (2017), a desktop film about the crowd-sourced investigation on Reddit following the Boston bombing of 2013. As the director breaks down Kennedy’s film, analysing its narrative construction and its tendency for geometric abstraction, she voluntarily gets caught in an ‘analytical frenzy’, not unlike the Redditors themselves. As Galibert-Laîné seamlessly chains one stream of thought after another, her film evolves into a meta-reflection on our relation to images and our compulsion to create meaning from visual material. If  What remains of the modernist dream of reshaping human societies from the ground up based on scientific, rationalist principles? Goldstein and Zielke’s ambitious, erudite and formally complex city symphony seeks to find out. Its subject is Brasilia, the artificially created capital of Brazil that architects Oscar Niemeyer and Lúcio Costa forged out of the wilderness in the late fifties. The imposing geometric forms of the city, expressly conceived in cosmic terms and perfected like Kubrickian monoliths from outer space, appear to have all but snuffed out human presence. Machine sees this city as an otherworldly geography unfit for human life, but also allowing the possibilities of imagining utopias, catholic cultists, freemasons, biker gangs and Esperanto evangelists all finding a home within Brasilia’s orbit. Employing heterogenous narrative modes, Goldstein and Zielke develop a visually striking portrait of a city that has come to resemble a religious monument in itself, demanding awestruck worship and constant maintenance by people who can’t afford to live here. Their Brasilia is either a place that inspires dreams of reimagining life or an abyss where dreams come to die. Even as it looks back at a moment in modern intellectual history, Machine evokes questions about the future, inviting us to reflect on the eternal human desire to play demiurge.

What remains of the modernist dream of reshaping human societies from the ground up based on scientific, rationalist principles? Goldstein and Zielke’s ambitious, erudite and formally complex city symphony seeks to find out. Its subject is Brasilia, the artificially created capital of Brazil that architects Oscar Niemeyer and Lúcio Costa forged out of the wilderness in the late fifties. The imposing geometric forms of the city, expressly conceived in cosmic terms and perfected like Kubrickian monoliths from outer space, appear to have all but snuffed out human presence. Machine sees this city as an otherworldly geography unfit for human life, but also allowing the possibilities of imagining utopias, catholic cultists, freemasons, biker gangs and Esperanto evangelists all finding a home within Brasilia’s orbit. Employing heterogenous narrative modes, Goldstein and Zielke develop a visually striking portrait of a city that has come to resemble a religious monument in itself, demanding awestruck worship and constant maintenance by people who can’t afford to live here. Their Brasilia is either a place that inspires dreams of reimagining life or an abyss where dreams come to die. Even as it looks back at a moment in modern intellectual history, Machine evokes questions about the future, inviting us to reflect on the eternal human desire to play demiurge. Tamhane’s superb second film feels like home territory for him. Sharad, an apprentice Hindustani music singer, is not the greatest of talents, but imagines himself as part of a tradition, one that gives a structural meaning to his life. But, the promise of omnipresence and instant gratification of the modern world beckoning him, not only does he find himself unable to live up to the lofty ideals of his tradition, he’s also is gradually disabused of these ideals themselves. In a very direct manner, The Disciple zeroes in on a fundamental, civilizational sentiment that underpins artistic succession in the subcontinent: that of filial piety, as opposed to the parricidal narrative that informs the Western conception of self-realization. Even when his faith has been questioned, Sharad continues to serve his elderly teacher, caring for him till the final days, like icon worshippers who hold on to their idols even (and especially) when the meaning behind them is lost. Tamhane builds up gradually to this assault on Sharad’s worldview, with humour, suspense and a calculated formal reserve that redoubles the impact of the emotional violence. His film invites viewers to constantly process narrative information in order to access it, providing a rich dividend for the effort.

Tamhane’s superb second film feels like home territory for him. Sharad, an apprentice Hindustani music singer, is not the greatest of talents, but imagines himself as part of a tradition, one that gives a structural meaning to his life. But, the promise of omnipresence and instant gratification of the modern world beckoning him, not only does he find himself unable to live up to the lofty ideals of his tradition, he’s also is gradually disabused of these ideals themselves. In a very direct manner, The Disciple zeroes in on a fundamental, civilizational sentiment that underpins artistic succession in the subcontinent: that of filial piety, as opposed to the parricidal narrative that informs the Western conception of self-realization. Even when his faith has been questioned, Sharad continues to serve his elderly teacher, caring for him till the final days, like icon worshippers who hold on to their idols even (and especially) when the meaning behind them is lost. Tamhane builds up gradually to this assault on Sharad’s worldview, with humour, suspense and a calculated formal reserve that redoubles the impact of the emotional violence. His film invites viewers to constantly process narrative information in order to access it, providing a rich dividend for the effort. In Unusual Summer, Aljafari repurposes CCTV tapes that his father left behind after his death in 2015. The tapes are from the summer of 2006 and were used record the parking spot outside his home to see who’s been breaking the car window. Despite the dramatic promises of the CCTV aesthetic and the location of the house in the crime-ridden district of Ramla, what we get in this film are quotidian incidents, sightings of neighbours passing by, the picture of a town going about everyday business. Aljafari adds a sparse ambient soundtrack that imparts Tati-esque colour to the proceedings, with the passers-by on screen becoming veritable characters. This transformation of private surveillance footage into a session of window-watching and people-spotting produces a feeling of community and forges a relation of inheritance between the filmmaker and his father, the only two people to have seen these tapes. Supremely calming though it is, Unusual Summer is also seared by loss and mourning, the familiar faces, places, animals and trees that register like spectral presences on the lo-fi video having vanished in the intervening years following intrusions by the Israeli state. A minimalist gem that speaks to our now-amplified urge to reach out to others.

In Unusual Summer, Aljafari repurposes CCTV tapes that his father left behind after his death in 2015. The tapes are from the summer of 2006 and were used record the parking spot outside his home to see who’s been breaking the car window. Despite the dramatic promises of the CCTV aesthetic and the location of the house in the crime-ridden district of Ramla, what we get in this film are quotidian incidents, sightings of neighbours passing by, the picture of a town going about everyday business. Aljafari adds a sparse ambient soundtrack that imparts Tati-esque colour to the proceedings, with the passers-by on screen becoming veritable characters. This transformation of private surveillance footage into a session of window-watching and people-spotting produces a feeling of community and forges a relation of inheritance between the filmmaker and his father, the only two people to have seen these tapes. Supremely calming though it is, Unusual Summer is also seared by loss and mourning, the familiar faces, places, animals and trees that register like spectral presences on the lo-fi video having vanished in the intervening years following intrusions by the Israeli state. A minimalist gem that speaks to our now-amplified urge to reach out to others. Dutta’s richly dialectical new film draws out themes from

Dutta’s richly dialectical new film draws out themes from  The Ross brothers’ new docuficion follows the last day of operation of The Roaring 20s, a downscale bar fictionally set in Las Vegas, at which a bevy of social castaways gather to mourn and celebrate. While all the actors play themselves, the filmmakers loosely fictionalize the scenario, giving direction to it with certain pertinent themes. Set against the backdrop of collapsing American businesses, Bloody Nose is a hymn for failure, a note of solidarity to what the American lexicon calls “losers”. The Roaring 20s is the opposite of everything one associates with the glitz and glamour of Sin City: it’s a floundering venture that is the negative image of the American Dream. For its regulars, however, the bar is something of an institution that provides them with a public (and, at times, private) space that has become scarce elsewhere and where they can be themselves. The film’s broader view of class is compounded by a specific generational perspective that refutes the idea that the young, the ‘millennials’, can’t make it because they don’t work hard enough. A film that hits the right moods without tipping over into condescension or miserabilism, Bloody Nose deserves all the plaudits it’s been getting.

The Ross brothers’ new docuficion follows the last day of operation of The Roaring 20s, a downscale bar fictionally set in Las Vegas, at which a bevy of social castaways gather to mourn and celebrate. While all the actors play themselves, the filmmakers loosely fictionalize the scenario, giving direction to it with certain pertinent themes. Set against the backdrop of collapsing American businesses, Bloody Nose is a hymn for failure, a note of solidarity to what the American lexicon calls “losers”. The Roaring 20s is the opposite of everything one associates with the glitz and glamour of Sin City: it’s a floundering venture that is the negative image of the American Dream. For its regulars, however, the bar is something of an institution that provides them with a public (and, at times, private) space that has become scarce elsewhere and where they can be themselves. The film’s broader view of class is compounded by a specific generational perspective that refutes the idea that the young, the ‘millennials’, can’t make it because they don’t work hard enough. A film that hits the right moods without tipping over into condescension or miserabilism, Bloody Nose deserves all the plaudits it’s been getting. Perel continues his exploration into Argentina’s military dictatorship by examining the role of large private corporations in enabling and carrying out state-sponsored pogroms against political dissidents of the junta. He photographs the company facilities as they are today while a brisk voiceover lists out how each firm helped military and security forces detain, torture and get rid of problematic workers in exchange for financial perks. The text, read out from an official 2015 report, is numbingly repetitious, and drives home the pervasiveness of these military-industrial operations. Perel’s decision to frame the sites through his car’s windshield creates a sense of illicit access, even though there is visibly little stopping him from going nearer the facilities. Some of the companies continue to operate under their own name, while some others have changed, with at least one site carrying a memorial sign for the injustice perpetrated there. Perel is, in effect, photographing the ur-filmic image of factory entrances, but all we see is a handful of vehicles leaving the gates. This eerie absence of human figures evokes the disappeared workers who, at some companies, were picked up at the entrance, a site, as

Perel continues his exploration into Argentina’s military dictatorship by examining the role of large private corporations in enabling and carrying out state-sponsored pogroms against political dissidents of the junta. He photographs the company facilities as they are today while a brisk voiceover lists out how each firm helped military and security forces detain, torture and get rid of problematic workers in exchange for financial perks. The text, read out from an official 2015 report, is numbingly repetitious, and drives home the pervasiveness of these military-industrial operations. Perel’s decision to frame the sites through his car’s windshield creates a sense of illicit access, even though there is visibly little stopping him from going nearer the facilities. Some of the companies continue to operate under their own name, while some others have changed, with at least one site carrying a memorial sign for the injustice perpetrated there. Perel is, in effect, photographing the ur-filmic image of factory entrances, but all we see is a handful of vehicles leaving the gates. This eerie absence of human figures evokes the disappeared workers who, at some companies, were picked up at the entrance, a site, as  Lynne Sachs’ frank, morally messy documentary turns around her father, Ira Sachs Sr., a ‘hippie businessman’ whose unconventional living and constant womanizing comes down heavily upon his nine children, some of whom have known the existence of the others only after decades. Sachs weaves through footage shot over half a century in half a dozen formats and layers it carefully into a simple, direct account with a voiceover addressed at the audience. She takes what could’ve been a narrow family melodrama into much stickier territory. Her film isn’t a portrait of her father, but a meditation on relationships with this man as the connecting element. Sachs goes beyond all gut responses to her father’s behaviour—disappointment, rage, disgust—towards a complex human reality that can elicit only inchoate sentiments, as suggested by the film’s incomplete title. She isn’t filming people or their stories, but the spaces between people, and how these spaces are always mediated by the actions of others. Father’s wayward life, itself rooted perhaps in a traumatic childhood, profoundly shapes the way his children look at each other. Sachs’ film is ostensibly a massive unburdening project for her; that she has been able to draw out its broader implications is a significant accomplishment.

Lynne Sachs’ frank, morally messy documentary turns around her father, Ira Sachs Sr., a ‘hippie businessman’ whose unconventional living and constant womanizing comes down heavily upon his nine children, some of whom have known the existence of the others only after decades. Sachs weaves through footage shot over half a century in half a dozen formats and layers it carefully into a simple, direct account with a voiceover addressed at the audience. She takes what could’ve been a narrow family melodrama into much stickier territory. Her film isn’t a portrait of her father, but a meditation on relationships with this man as the connecting element. Sachs goes beyond all gut responses to her father’s behaviour—disappointment, rage, disgust—towards a complex human reality that can elicit only inchoate sentiments, as suggested by the film’s incomplete title. She isn’t filming people or their stories, but the spaces between people, and how these spaces are always mediated by the actions of others. Father’s wayward life, itself rooted perhaps in a traumatic childhood, profoundly shapes the way his children look at each other. Sachs’ film is ostensibly a massive unburdening project for her; that she has been able to draw out its broader implications is a significant accomplishment. As part of his work, Lashay T. Warren, a young family man from Los Angeles, is posted in Cal City, California, a town wrought in the fifties by a lone developer out of the Mojave Desert with the hope that it would become the next Los Angeles—a dream that didn’t come to fruition. Along with other men and women his age, Lashay is responsible for maintaining this ghost town by reclaiming its streets from nature and restoring some semblance of cartographic order. Victoria teases out various thematic layers from this singular scenario. On one level, it is an absurd tale about one of the many dead ends of capitalist enterprise, a kind of anti-Chinatown portrait of a Los Angeles that could’ve been. Lashay is like a worker repairing a remote outpost in space, marvelling at every sign of life in this almost otherworldly landscape. But he also resembles the American pioneers, whose diaries on their way to the West he emulates in the film’s voiceover. Ultimately, Victoria is a poignant, humanist document, in the vein of Killer of Sheep, about the dignity of a young Black man providing for his family, trying to graduate from high school, all the while fighting the gravity of Compton’s streets.

As part of his work, Lashay T. Warren, a young family man from Los Angeles, is posted in Cal City, California, a town wrought in the fifties by a lone developer out of the Mojave Desert with the hope that it would become the next Los Angeles—a dream that didn’t come to fruition. Along with other men and women his age, Lashay is responsible for maintaining this ghost town by reclaiming its streets from nature and restoring some semblance of cartographic order. Victoria teases out various thematic layers from this singular scenario. On one level, it is an absurd tale about one of the many dead ends of capitalist enterprise, a kind of anti-Chinatown portrait of a Los Angeles that could’ve been. Lashay is like a worker repairing a remote outpost in space, marvelling at every sign of life in this almost otherworldly landscape. But he also resembles the American pioneers, whose diaries on their way to the West he emulates in the film’s voiceover. Ultimately, Victoria is a poignant, humanist document, in the vein of Killer of Sheep, about the dignity of a young Black man providing for his family, trying to graduate from high school, all the while fighting the gravity of Compton’s streets.

While multiple films this year about old age have presented it as a time of reckoning, Kore-eda’s European project The Truth offers an honest, rigorous and profoundly generous picture of life’s twilight. In a career-summarizing role, Catherine Deneuve plays a creature of surfaces, a vain actress who struts in leopard skin and surrounds herself with her own posters. Her Fabienne is a pure shell without a core who can never speak in the first person. She has written an autobiography, but it’s a sanitized account, a reflection of how her life would rather have been. “Truth is boring”, she declares. Responding to her daughter Lumir’s (Juliette Binoche) complaint that she ignored her children for work, she bluntly states that she prefers to be a good actress than a good person. Behaviour precedes intent in the mise en abyme of Kore-eda’s intricate monument to aging, as performance becomes a means of expiation and a way of relating to the world. A work overflowing with sensual pleasures as well as radical propositions, The Truth rejects the dichotomy between actor and role, both in the cinematic and the existential sense. In the end, Fabienne and her close ones come together as something resembling a family. That, assures Kore-eda’s film, is good enough.

While multiple films this year about old age have presented it as a time of reckoning, Kore-eda’s European project The Truth offers an honest, rigorous and profoundly generous picture of life’s twilight. In a career-summarizing role, Catherine Deneuve plays a creature of surfaces, a vain actress who struts in leopard skin and surrounds herself with her own posters. Her Fabienne is a pure shell without a core who can never speak in the first person. She has written an autobiography, but it’s a sanitized account, a reflection of how her life would rather have been. “Truth is boring”, she declares. Responding to her daughter Lumir’s (Juliette Binoche) complaint that she ignored her children for work, she bluntly states that she prefers to be a good actress than a good person. Behaviour precedes intent in the mise en abyme of Kore-eda’s intricate monument to aging, as performance becomes a means of expiation and a way of relating to the world. A work overflowing with sensual pleasures as well as radical propositions, The Truth rejects the dichotomy between actor and role, both in the cinematic and the existential sense. In the end, Fabienne and her close ones come together as something resembling a family. That, assures Kore-eda’s film, is good enough. The across-the-board success of Parasite invites two possible inferences: either that the cynical logic of capital can steer a searing critique of itself to profitable ends or that this twisted tale of upward ascension appeals to widely-held anxiety and resentment. Whatever it is, Bong Joon-ho’s extraordinary, genre-bending work weds a compelling social parable to a vital, pulsating form that doesn’t speak to current times as much as activate something primal, mythical in the viewer. With a parodic bluntness reminiscent of the best of seventies cinema, Bong pits survivalist working-class resourcefulness with self-annihilating bourgeois prejudice and gullibility, the implied sexual anarchy never exactly coming to fruition. He orchestrates the narrative with the nimbleness and legerdemain of a seasoned magician, the viewer’s sympathy for any of the characters remaining contingent and constantly forced to realign itself from scene to scene. Parasite is foremost a masterclass in describing space, in the manner in which Bong synthesizes the bunker-like shanty of the working-class family with the high-modernist household of their upper-class employers, tracing direct metaphors for the film’s themes within its topology. It’s a work that progresses with the inevitability of a boulder running down a hill. And how spectacularly it comes crashing.

The across-the-board success of Parasite invites two possible inferences: either that the cynical logic of capital can steer a searing critique of itself to profitable ends or that this twisted tale of upward ascension appeals to widely-held anxiety and resentment. Whatever it is, Bong Joon-ho’s extraordinary, genre-bending work weds a compelling social parable to a vital, pulsating form that doesn’t speak to current times as much as activate something primal, mythical in the viewer. With a parodic bluntness reminiscent of the best of seventies cinema, Bong pits survivalist working-class resourcefulness with self-annihilating bourgeois prejudice and gullibility, the implied sexual anarchy never exactly coming to fruition. He orchestrates the narrative with the nimbleness and legerdemain of a seasoned magician, the viewer’s sympathy for any of the characters remaining contingent and constantly forced to realign itself from scene to scene. Parasite is foremost a masterclass in describing space, in the manner in which Bong synthesizes the bunker-like shanty of the working-class family with the high-modernist household of their upper-class employers, tracing direct metaphors for the film’s themes within its topology. It’s a work that progresses with the inevitability of a boulder running down a hill. And how spectacularly it comes crashing. Vitalina Varela is an emblem of mourning. In recreating a harrowing moment in her life for the film, the middle-aged Vitalina, who comes to Lisbon following her husband’s death, instils her loss with a meaning. It’s a film not of political justice but individual injustice, the promise to Vitalina the that men in their resignation and madness have forgotten. It’s also a bleak, relentless work of subtractions. What is shown is arrived at by chipping away what can’t/won’t be shown, this formal denuding reflective of the increasing dispossession of the Cova da Moura shantytown we see in the film. Costa’s Matisse-like delineation of figure only suggests humans, enacting the ethical problems of representation in its plastic scheme. The film is on a 4:3 aspect ratio, but the viewer hardly perceives that, the localized light reducing the visual field to small pockets of brightness. Vitalina is a film of and about objects, whose vanishing echoes the community’s dissolution and whose presence embodies Vitalina’s assertive spirit. Her voice has its own materiality, her speech becomes her means to survival. Costa’s film is a vision of utter despair, a cold monument with an uplifting, absolutely essential final shot. A dirge, in effect.