Let’s begin by stating the obvious: Cinéma du réel, Paris, programmes weird stuff. Its main offering could be broadly described as experimental documentaries: works recognizably grappling with the real world, but demonstrating a strong commitment to formal innovation of the kind that challenges both our expectations of a film’s ostensible subject and our notion of what documentaries are. Rarely does one find in the festival’s lineup the sort of production that oils the machinery of the international documentary market. Few issue-based expository works are to be found here, hardly any fly-on-the-wall records, and no human-interest stories with appealing protagonists and clear dramaturgy.

The tendency is instead to embrace gaps, hesitations, ellipses, rough edges, acts of self-sabotage and blind leaps into the void. The image and sound in any given title in the selection are almost always orthogonal, the work deriving its meaning and affect instead from their dialectical organization. Films that may look like stubs, doodles, outtakes or half-formed sketches, by dint of adventurous curation and passionate presentation (evident from the insightful catalogue texts produced by the programming team), come to demand from the viewer a different way of looking and listening, and often a renewed conception of what a documentary can be.

Consider, for instance, Look Through My Eyes and Give Me Your Own. Noëlle Pujol’s half-hour documentary features the filmmaker walking through Cubist pioneer Georges Braque’s studio in Varengeville-sur-Mer, Northern France. For the most part, the camera surveys the now abandoned structure, taken over by nature, and the vestiges of human culture still visible on its walls. Recalling Picasso’s aphorism “I don’t search, I find”, Pujol’s casual, liberatingly purposeless gaze roves about before resting on a small, exotic bird perched on a wire inside the studio. Unfazed by the intruder, the gorgeous little creature stares back at the camera, which resumes its aimless drift after this uncanny encounter.

Free of a conceptual framework or a conventional narrative outline, Pujol’s film is only as discursive as the viewer wants it to be. The same goes for Léo Bizeul’s Robert Taschen (whose synopsis simply reads “A man in his home.”). A seven-minute portrait of a poor, middle-aged man eking it out in a nondescript hovel, Bizeul’s beautifully shot but bafflingly sparse film furnishes very little that is specific beyond its title. Yet the sharpened quality of attention that it extracts from us, and the duration it imposes, elevate this everyman into a subject worthy of a renaissance tableau.

The longer works in the selection equally reflect this resistance to clear exposition and overarching meaning. Films such as Luo Li’s Air Base, Gaspard Hirschi’s I Am Night at Noonday and Ico Costa’s Balane 3 are, at the outset, quasi-sociological studies set in particular locations, but even so, they play it loose, letting their framing concept fall apart under the weight of stylization. Li’s film is nominally set around a hobbyist fishing pond in Wuhan just after the easing of pandemic restrictions. What begins like a record of the psychological toll of the lockdown takes vast excursions to observe the city through a slightly absurdist lens, full of formal rhymes and quirky images. The result grasps at a poetic truth rather than a rational analysis.

I Am Night at Noonday takes off, in fact, from a highly literary idea: dressed as Don Quixote, theatre director Manolo Bez wanders around Marseille on a horse along with a reluctant Sancho, a pizza guy named Daniel Saïd on a motorbike, engaging in humorous encounters with the people and landscapes of the port city. A relatively classical satire in the line of Borat (2006), the film employs Quixote’s outsider perspective to expose the paranoia and distrust gripping the racially diverse but economically polarized city. Yet the film scrambles this setup midway, segueing first into a cinema-vérité mode that allows Bez and Saïd to step out of their characters to address the camera as their real selves.

Coursing through the Cinéma du réel programme is the general sense that reality can only be accessed obliquely, through an elliptical form that conceals as much as it reveals. Two of the most remarkable films in the programme take this throughline to a conclusion of sorts, adapting a refusal to image the human body. Maureen Fazendeiro’s Les Habitants is set in an unnamed French village. We see this quaint commune go about its immutable routine, its picturesque streets well-maintained, its meadows neatly kept and its many glasshouses yielding rich produce. On the soundtrack, we hear letters from a mother to her daughter recounting the arrival of a group of Roma into the village, the opposition of the municipality to their presence and the material support that a few of the villagers offer to their nomadic guests.

Featuring interesting repetitions of banal information, the film’s voiceover offers a site of dramatic conflict – between the efforts of those trying to legally evict the squatters and those helping them prolong their stay in the village – while the visuals present a source of harmony. This contradiction between the sordid living conditions of the Roma group detailed on the soundtrack and the plush, first-world life on display serves to throw into relief the violence underlying suburban order. In filming the village after the immigrants’ departure, and refusing to feature them in any shape or form, Les Habitants points up cinema’s delay in keeping up with reality while also exploring the creative possibilities of this delay, of this spectral absence.

Elisabeth Subrin’s Manal Issa, 2024 goes further, eliminating the human body altogether. This ten-minute film is a companion piece to Subrin’s powerful 2022 work, Maria Schneider, 1983, in which the filmmaker had three actresses of varied backgrounds reenact an interview that Schneider gave for a French television show. In the interview, a visibly uncomfortable Schneider discusses the second-class treatment that actresses suffer in the industry, reveals that she turns down a lot of roles, deflects questions about Last Tango in Paris (1972) and generally resists the niceties and rituals of movie journalism. While the actors in Subrin’s film fastidiously re-create Schneider’s look and diction, they bring their own perspectives to bear upon the reenactment, locating themselves in Schneider’s experience as an exploited, marginalized film worker while extending her activist legacy to the present.

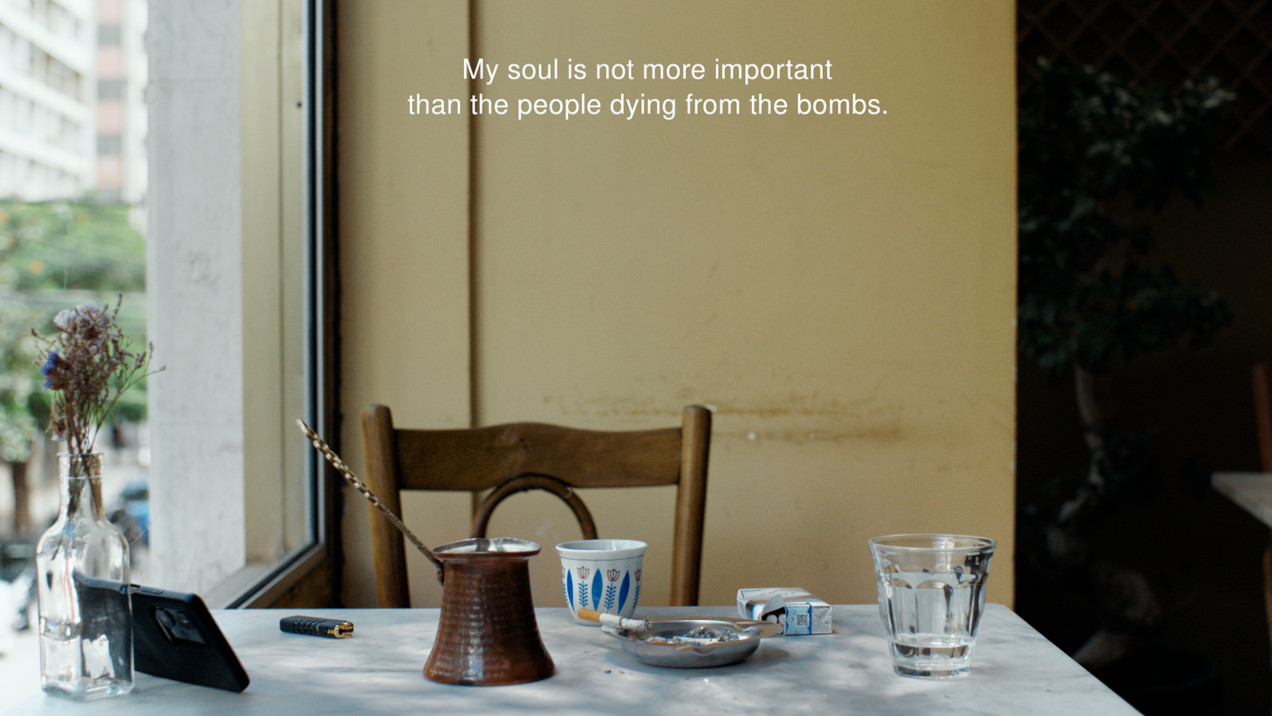

Where Maria Schneider, 1983 created doubles, excess bodies, Manal Issa, 2024 proposes a negation, one body too few. Here, Subrin poses to the Lebanese-French actress Manal Issa, one of the three participants of the former film, the same questions that Schneider was posed in the original interview. A publicly vocal actress, Issa talks about the poverty of meaningful roles offered to Arab-origin actresses, the limitations of the capitalist production model, the choice of moving back to Lebanon during crisis and the importance of speaking up against political iniquity. While we listen to her responses, Issa herself remains offscreen; all that we see is a table by the window containing signs of human presence: a pack of cigarettes, a lighter, an ashtray, a tea cup, a glass of water and a smartphone.

Issa’s refusal to take up pointless roles to sustain a career, to maintain a screen presence while censoring her critical voice, is echoed by Subrin’s refusal to show her. “If I’m on screen I’m something, and if I’m not I’m nothing? Khalas?” asks the actress, adding that she feels punished for her political opinions, for calling out Israel’s bombing of Gaza. “If I can’t be true to myself, there is no point showing myself,” Issa concludes, as the camera gently pans from the table to a street outside the window. Like Schneider’s, Issa’s self-negation stems from an outlook that privileges life over films, reality over fiction. Six hours after the filming, an end card notes, “Israeli airstrikes escalated throughout Lebanon, killing over 500 people in one day.”