2022 witnessed the demise of several towering figures of cinematic modernism, none more iconic than Jean-Luc Godard. With their passing, it really feels like the end of a chapter in the story of film, one in which cinema was the privileged artform to interrogate history and the world. But their death also registers as strangely liberating in a way, like a clearing in the woods produced by fallen trees that allows us a new, privileged view. Let us hope that the work of these giants will continue to guide filmmakers and critics in their thought and practice.

In August this year, I was lucky to attend the 75th Locarno Film Festival, my first fest outside India. Basking in the gorgeous summertime scenery of Ticino and soaking up the equally sumptuous Douglas Sirk retrospective was an experience to remember, but I’m most grateful for the chance to get to know some terrific people from around the globe, among them cinephiles, curators and critics I’d known online for years but had never met. I’m truly grateful for their insight and company. Mistake: not reaching out to Luc Moullet when I was in Paris after the festival.

In a year that saw the world return to some semblance of normalcy,[citation needed] my own moviegoing habits seemed to have changed for good. The Locarno festival notwithstanding, I went to the theatres, I think, no more than four times this year (Vikram, Ponniyin Selvan: I, Kantara (all 2022) and the 50th anniversary re-release of The Godfather (1972)), which is four more than the last year. Ominous signs. That said, I was fortunate to watch three silent films on 35mm with mesmerizing live piano accompaniment at a King Vidor retrospective at the Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé Foundation in Paris in September: The Sky Pilot (1921), Wine of Youth (1924) and The Crowd (1928), the latter screening a highlight of my cinephile life.

Although I saw more films this year than any other in my memory, I didn’t watch as many new productions as I normally would, especially from India. Despite the absurd overvaluation it has been subject to in the West, I haven’t see a finer action movie in the recent past than RRR, which felt like a masterclass on how to imbue action with emotional-moral stakes, the missing soul of so many contemporary blockbusters. For all its saturated spectacle, RRR is a minimal film in the way it weaves the fewest of narrative elements in different combinations to emphatic, expressive ends. Gehraaiyaan was a compelling piece of slick, professional filmmaking, as was Jalsa. I’ve always admired the streak of self-sabotage in the career of Gautam Menon, and his superb gangster epic Vendhu Thanindhathu Kaadu harnesses that impulse productively, channelling it through screenwriter Jeyamohan’s touching, tragic vision.

A good part of my viewing this year consisted of a dive into Iranian cinema, which, I can say for certain now, is my single favourite national cinema. Among the 200-odd auteur and genre films (from native as well as expatriate Iranian directors) that I watched, there was very little that I disliked, scores of great works and at least two dozen masterpieces. I hope to publish a list soon. In the meantime, check out Another Screen‘s formidable programme dedicated to Iranian/Iranian-origin women filmmakers, which ends on the 4th of January.

Other personal discoveries this year were the films of Costa-Gavras (Picks: Family Business (1986) and Music Box (1989)), the mid-tier features of Boris Barnet (on whose Lyana (1955) I wrote a text for the amazing Outskirts magazine) and the astounding, hyper-caffeinated anime of Masaaki Yuasa (essay coming up). Without further ado, my favourite films of 2022:

1. Matter Out of Place (Nikolaus Geyrhalter, Austria)

If researchers a few hundred years from now were to try and understand how humankind lived in the year 2022 AD, they would do well to turn to Geyrhalter’s spellbinding Matter Out of Place, an expansive survey of foreign objects littering the remotest nooks of the earth. Filmed in a dozen locations on different continents, the film traces the planetary movement of human-generated waste, the great paradoxes shaping its production and the massive efforts needed to manage its proliferation. Garbage doesn’t just cover the landscape in Geyrhalter’s film, it becomes the landscape. With cheeky visual rhymes, astute sound design, proto-Lubitschian humour and a subtly psychoanalytic approach to the physical world, Matter unearths the repressed material unconscious underlying the enticements of consumer society and international tourism. But the film offers no easy answers, presenting instead a universe whose horrors and beauties are inextricably linked, one which evokes awe and terror at humanity’s godlike capacity to create and destroy. In its firm belief that the secrets of the world reveal themselves to the questioning camera eye, Geyrhalter’s work possesses a spiritual dimension directly sdescending from the writings of André Bazin, and his new film elevates the sight of rubbish into a religious epiphany.

If researchers a few hundred years from now were to try and understand how humankind lived in the year 2022 AD, they would do well to turn to Geyrhalter’s spellbinding Matter Out of Place, an expansive survey of foreign objects littering the remotest nooks of the earth. Filmed in a dozen locations on different continents, the film traces the planetary movement of human-generated waste, the great paradoxes shaping its production and the massive efforts needed to manage its proliferation. Garbage doesn’t just cover the landscape in Geyrhalter’s film, it becomes the landscape. With cheeky visual rhymes, astute sound design, proto-Lubitschian humour and a subtly psychoanalytic approach to the physical world, Matter unearths the repressed material unconscious underlying the enticements of consumer society and international tourism. But the film offers no easy answers, presenting instead a universe whose horrors and beauties are inextricably linked, one which evokes awe and terror at humanity’s godlike capacity to create and destroy. In its firm belief that the secrets of the world reveal themselves to the questioning camera eye, Geyrhalter’s work possesses a spiritual dimension directly sdescending from the writings of André Bazin, and his new film elevates the sight of rubbish into a religious epiphany.

2. Crimes of the Future (David Cronenberg, Canada)

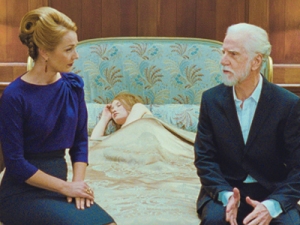

Somewhere in the dematerialized wastelands of Cosmopolis (2012), overrun now by the vacuous celebrity culture of Maps to the Stars (2014), lives Saul Tenser, an “artist of the inner landscape” who grows new organs that are surgically removed by his partner Caprice during their feted public performances. Saul is a conservative in denial of the rapid transformation the human body is undergoing—a Clint Eastwood of the New Flesh—who would rather excise his new organs than embrace his true, deviant self. As governments and corporates look to quell the insurrection triggered by a cult of anti-Luddite ecoterrorists who sabotage not technology but the human body, Saul must decide whether to remain at the mercy of the algorithms or take the evolutionary leap. The most rewarding way to approach Cronenberg’s stellar, career-capping new work is to take it not as an allegory of current political debates, but literally. In Crimes of the Future, the body is indeed the final frontier, the last repository of all meaning, the sole means to spiritual edification or revolutionary change—a truism already in our Age of the Body. Filled wall-to-wall with dad jokes and dumb exposition, Cronenberg’s silly, sublime, supremely stylish treatise on corporeal capitalism is the most thought-provoking film since Pain and Gain (2013).

Somewhere in the dematerialized wastelands of Cosmopolis (2012), overrun now by the vacuous celebrity culture of Maps to the Stars (2014), lives Saul Tenser, an “artist of the inner landscape” who grows new organs that are surgically removed by his partner Caprice during their feted public performances. Saul is a conservative in denial of the rapid transformation the human body is undergoing—a Clint Eastwood of the New Flesh—who would rather excise his new organs than embrace his true, deviant self. As governments and corporates look to quell the insurrection triggered by a cult of anti-Luddite ecoterrorists who sabotage not technology but the human body, Saul must decide whether to remain at the mercy of the algorithms or take the evolutionary leap. The most rewarding way to approach Cronenberg’s stellar, career-capping new work is to take it not as an allegory of current political debates, but literally. In Crimes of the Future, the body is indeed the final frontier, the last repository of all meaning, the sole means to spiritual edification or revolutionary change—a truism already in our Age of the Body. Filled wall-to-wall with dad jokes and dumb exposition, Cronenberg’s silly, sublime, supremely stylish treatise on corporeal capitalism is the most thought-provoking film since Pain and Gain (2013).

3. A German Party (Simon Brückner, Germany)

Politics is dirty, and electoral politics doubly so. Few filmmakers possess the curiosity, intellectual mettle and good faith—leave alone the necessary access—to examine the unglamorous negotiations and compromises that are fundamental to the democratic process. Made over three years, Simon Brückner’s magnificent fly-on-the-wall documentary about the workings of the far-right German outfit Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) immerses us into the party’s operations, ranging from cool deliberations of executive meetings to high-temperature grassroots confrontations. The result is a markedly composite picture that offers a sense of the heterogeneity of an organization popularly considered an ideological monolith. Over six illuminating chapters, A German Party presents a political body fully caught up in the dialectical process of self-definition, an organization trying to identify itself through differentiation. The need for the AfD to go mainstream, to form alliances and influence policy runs up against the image that it has built for itself, namely that it represents a force outside the establishment. The most intriguing suggestion of Brückner’s film may be that rightward shift of the party, far from signalling the formation of a coherent ideology, may actually be the fruit of a lack of clear identity. Whether the AfD is the elephant in the room or a paper tiger, A German Party leaves it to the viewer to judge.

Politics is dirty, and electoral politics doubly so. Few filmmakers possess the curiosity, intellectual mettle and good faith—leave alone the necessary access—to examine the unglamorous negotiations and compromises that are fundamental to the democratic process. Made over three years, Simon Brückner’s magnificent fly-on-the-wall documentary about the workings of the far-right German outfit Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) immerses us into the party’s operations, ranging from cool deliberations of executive meetings to high-temperature grassroots confrontations. The result is a markedly composite picture that offers a sense of the heterogeneity of an organization popularly considered an ideological monolith. Over six illuminating chapters, A German Party presents a political body fully caught up in the dialectical process of self-definition, an organization trying to identify itself through differentiation. The need for the AfD to go mainstream, to form alliances and influence policy runs up against the image that it has built for itself, namely that it represents a force outside the establishment. The most intriguing suggestion of Brückner’s film may be that rightward shift of the party, far from signalling the formation of a coherent ideology, may actually be the fruit of a lack of clear identity. Whether the AfD is the elephant in the room or a paper tiger, A German Party leaves it to the viewer to judge.

4. Stomp (Sajas & Shinos Rahman, India)

The Rahman brothers’ boundary-smashing formalist work is nominally a documentary about a theatre group named the Little Earth School of Theatre. For the most part, the film showcases the troupe’s preparations for an upcoming performance at the annual function of a middle-class housing association in Kerala. We see the company’s rehearsal in considerable detail, their work on gesture, movement, voice and cadence, but the nature of their play is sketchy and elusive, like pieces of a puzzle that never fit. Rejecting literary and psychological explanations, Chavittu subverts the conventional artist profile, supplying no commentary on the meaning or significance of the rehearsal and complicating it with absurd interludes. What the filmmakers offer instead is a bracing procedural work intently focused on the physicality of its subjects, emptied of emotional life and operating together as a consummate professional unit. The sensuality that the film radiates comes not through dramatic or formal devices, but from the raw presence of young, athletic bodies populating the frame. Even when it places this performance within a satirical, self-reflexive social context, the film remains gentle, focused on the troupe’s single-minded artistry in the face of indifference and marginalization. Chavittu is all grace.

The Rahman brothers’ boundary-smashing formalist work is nominally a documentary about a theatre group named the Little Earth School of Theatre. For the most part, the film showcases the troupe’s preparations for an upcoming performance at the annual function of a middle-class housing association in Kerala. We see the company’s rehearsal in considerable detail, their work on gesture, movement, voice and cadence, but the nature of their play is sketchy and elusive, like pieces of a puzzle that never fit. Rejecting literary and psychological explanations, Chavittu subverts the conventional artist profile, supplying no commentary on the meaning or significance of the rehearsal and complicating it with absurd interludes. What the filmmakers offer instead is a bracing procedural work intently focused on the physicality of its subjects, emptied of emotional life and operating together as a consummate professional unit. The sensuality that the film radiates comes not through dramatic or formal devices, but from the raw presence of young, athletic bodies populating the frame. Even when it places this performance within a satirical, self-reflexive social context, the film remains gentle, focused on the troupe’s single-minded artistry in the face of indifference and marginalization. Chavittu is all grace.

5. Nazarbazi (Maryam Tafakory, Iran-UK)

The problem with film censorship, as Judith Williamson pointed out, isn’t that it rids movies of objectionable matter, but that it makes everything else seem dirty. Drawing images and sounds from almost a hundred Iranian films made since the 1979 revolution, overlaying them with evocative fragments of citations and original text, Maryam Tafakory’s ambitious, enrapturing video collage Nazarbazi illuminates how the Islamic regime’s censorship codes, specifically its restriction on showing men and women touching each other on screen, displaced this repressed sexuality onto other sensations, objects and aesthetic elements. An astonishing example of film criticism as an artwork in itself, Tafakory’s exhilarating, tactile montage locates the erotics of cinematic art in fluttering fabric, clinking bangles, slashed wrists, breaking glass, aromatic food, sweeping camera movements and, of course, the play of glances. Supressed desire finds a way to manifest not just in filmmakers’ cunning paraphrase of taboo actions, but simply in the ontology of the medium; sensuality in cinema is revealed not just as what artists express, but as what they can’t help but express, thanks to the inherent voluptuousness of moving bodies, caressing textures and resonating sounds. Watching Iranian films after Nazarbazi, you might find yourself asking the same question as Diane Keaton in Love and Death (1975): can we not talk about sex so much?

The problem with film censorship, as Judith Williamson pointed out, isn’t that it rids movies of objectionable matter, but that it makes everything else seem dirty. Drawing images and sounds from almost a hundred Iranian films made since the 1979 revolution, overlaying them with evocative fragments of citations and original text, Maryam Tafakory’s ambitious, enrapturing video collage Nazarbazi illuminates how the Islamic regime’s censorship codes, specifically its restriction on showing men and women touching each other on screen, displaced this repressed sexuality onto other sensations, objects and aesthetic elements. An astonishing example of film criticism as an artwork in itself, Tafakory’s exhilarating, tactile montage locates the erotics of cinematic art in fluttering fabric, clinking bangles, slashed wrists, breaking glass, aromatic food, sweeping camera movements and, of course, the play of glances. Supressed desire finds a way to manifest not just in filmmakers’ cunning paraphrase of taboo actions, but simply in the ontology of the medium; sensuality in cinema is revealed not just as what artists express, but as what they can’t help but express, thanks to the inherent voluptuousness of moving bodies, caressing textures and resonating sounds. Watching Iranian films after Nazarbazi, you might find yourself asking the same question as Diane Keaton in Love and Death (1975): can we not talk about sex so much?

6. Footnote (Zhengfan Yang, USA-China)

Terror floats in the air in Footnote, not just due to the pandemic, but also because the film’s soundtrack consists entirely of police radio communication from Chicago city. The incoming complaints are by turns petty and serious, ranging from minor disagreements with neighbours to drive-by shootings, and officers are tasked with everything from delivering a lost pet home to checking on isolated senior citizens. Seemingly gathered over a year, these excerpts reveal an extremely busy, probably understaffed police force grappling with the tensions of a diverse, multicultural city. The image, meanwhile, comprises wide-angle shots of open spaces filmed from a higher vantage point— intersections, highways, beaches, parking lots, rooftops—almost always featuring ant-like, solitary human figures animating the frame. Thanks to the thrillingly dialectical relation that Footnote sets up between sound and image, these calming panoramas become vehicles of anxiety, with human bodies turning into agents of both biological and criminal threat. Widening the chasm between the home and the world, the radio chatter colours the images with a feeling of alienation and paranoia. In the way the airwaves convert ordinary window views into something akin to CCTV footage, pregnant with dramatic incident, Footnote might be tapping into a fundamental psychological condition of life in America. Also, the finest Hitchcock remake in ages?

Terror floats in the air in Footnote, not just due to the pandemic, but also because the film’s soundtrack consists entirely of police radio communication from Chicago city. The incoming complaints are by turns petty and serious, ranging from minor disagreements with neighbours to drive-by shootings, and officers are tasked with everything from delivering a lost pet home to checking on isolated senior citizens. Seemingly gathered over a year, these excerpts reveal an extremely busy, probably understaffed police force grappling with the tensions of a diverse, multicultural city. The image, meanwhile, comprises wide-angle shots of open spaces filmed from a higher vantage point— intersections, highways, beaches, parking lots, rooftops—almost always featuring ant-like, solitary human figures animating the frame. Thanks to the thrillingly dialectical relation that Footnote sets up between sound and image, these calming panoramas become vehicles of anxiety, with human bodies turning into agents of both biological and criminal threat. Widening the chasm between the home and the world, the radio chatter colours the images with a feeling of alienation and paranoia. In the way the airwaves convert ordinary window views into something akin to CCTV footage, pregnant with dramatic incident, Footnote might be tapping into a fundamental psychological condition of life in America. Also, the finest Hitchcock remake in ages?

7. The Plains (David Easteal, Australia)

The Plains channels the spirit of Jeanne Dielman into Andrew Rakowski, a middle-aged lawyer who leaves office every evening just past 5 P.M. to drive home to suburban Melbourne. Easteal’s cyclical road movie formalizes this routine, filming Andrew’s commute over eleven different days of the year with a fixed camera from the back seat of his car. On some days, Andrew offers a lift to his colleague David (Easteal himself), probing the reticent young man on his private life while also generously talking about his own: relatives, career, romance, wealth, mental health. Literally compartmentalizing work and life, the commute creates a transitional zone where Andrew can view each as an escape from the grind of the other. It provides a moment of unwinding, freedom from roleplay that both life and work demand. Yet, for all the me-time the drive home affords, there is an eerie silence whenever Andrew isn’t chatting away or the radio isn’t on, as though this non-place, non-time were forcing him to reflect on Important Things. Despite the apparent sameness, every day brings small deviations that threaten Andrew’s reassuring routine, all accumulating into a powerful meditation on aging and the passing of time, a view of life’s parade from the wheel of his car.

The Plains channels the spirit of Jeanne Dielman into Andrew Rakowski, a middle-aged lawyer who leaves office every evening just past 5 P.M. to drive home to suburban Melbourne. Easteal’s cyclical road movie formalizes this routine, filming Andrew’s commute over eleven different days of the year with a fixed camera from the back seat of his car. On some days, Andrew offers a lift to his colleague David (Easteal himself), probing the reticent young man on his private life while also generously talking about his own: relatives, career, romance, wealth, mental health. Literally compartmentalizing work and life, the commute creates a transitional zone where Andrew can view each as an escape from the grind of the other. It provides a moment of unwinding, freedom from roleplay that both life and work demand. Yet, for all the me-time the drive home affords, there is an eerie silence whenever Andrew isn’t chatting away or the radio isn’t on, as though this non-place, non-time were forcing him to reflect on Important Things. Despite the apparent sameness, every day brings small deviations that threaten Andrew’s reassuring routine, all accumulating into a powerful meditation on aging and the passing of time, a view of life’s parade from the wheel of his car.

8. Red Africa (Alexander Markov, Russia)

Rivalling the best work of Sergei Loznitsa, Alexander Markov’s resplendent found-footage project samples propaganda and reportage films that the USSR made during the Cold War to strengthen its ties with newly liberated African states. In this gorgeous Sovcolor assemblage, we see Soviet Premiers and African heads of state visit each other amidst ceremony and pomp, exhibitions showcase the latest in Soviet culture and technology to the African public and students use the knowledge they have gained in Moscow for the betterment of their countries, whose exported resources return as value-added products from behind the Iron Curtain. It’s a poignant glimpse into a nascent utopia, a world that could have been, which hides as much as it reveals. With cunning visual associations, Red Africa recasts decolonisation as a formal process that concealed fundamental continuities between the departing Western powers and the Eastern hegemon. Uplifting notions of bilateral ties between Africa and the USSR are belied by the strictly unilateral flow of influence and ideology. In its attempts at creating a new world order, Markov’s sharp film demonstrates, the Soviet Union espoused anti-colonial struggles in fraught areas of the globe even as it held sway over its diverse republics—a tragic irony made apparent when the chickens came home to roost in 1991.

Rivalling the best work of Sergei Loznitsa, Alexander Markov’s resplendent found-footage project samples propaganda and reportage films that the USSR made during the Cold War to strengthen its ties with newly liberated African states. In this gorgeous Sovcolor assemblage, we see Soviet Premiers and African heads of state visit each other amidst ceremony and pomp, exhibitions showcase the latest in Soviet culture and technology to the African public and students use the knowledge they have gained in Moscow for the betterment of their countries, whose exported resources return as value-added products from behind the Iron Curtain. It’s a poignant glimpse into a nascent utopia, a world that could have been, which hides as much as it reveals. With cunning visual associations, Red Africa recasts decolonisation as a formal process that concealed fundamental continuities between the departing Western powers and the Eastern hegemon. Uplifting notions of bilateral ties between Africa and the USSR are belied by the strictly unilateral flow of influence and ideology. In its attempts at creating a new world order, Markov’s sharp film demonstrates, the Soviet Union espoused anti-colonial struggles in fraught areas of the globe even as it held sway over its diverse republics—a tragic irony made apparent when the chickens came home to roost in 1991.

9. The DNA of Dignity (Jan Baumgartner, Switzerland)

Jan Baumgartner’s moving, loosely fictionalized documentary The DNA of Dignity follows the patient, heroic work of individuals and organizations involved in identifying victims buried in mass graves during the Yugoslav wars. Along with bones, volunteers retrieve articles of clothing, toiletries and other knickknacks, all hinting at stories to be told of those they have outlived. With witnesses passing away each year and new structures waiting to be erected over these burial sites, the excavations are truly a race against time, fighting both political amnesia and nature’s complicity in the oblivion. In their quest to rescue war victims from anonymity, forensic scientists assemble excavated bones into skeletons, carry out DNA tests to ascertain identities and hand over the remains to grieving families, who haven’t had closure despite the end of the war and who confess to no longer being able to enjoy landscape without being reminded of what it hides. Baumgartner’s film obscures political and institutional details to focus on the scientific process, offering a fascinating, inspiring picture of the how the abstractions of science eventually coalesce into human stories. Its success lies in finding the right tone and distance necessary for a subject as grave and delicate.

Jan Baumgartner’s moving, loosely fictionalized documentary The DNA of Dignity follows the patient, heroic work of individuals and organizations involved in identifying victims buried in mass graves during the Yugoslav wars. Along with bones, volunteers retrieve articles of clothing, toiletries and other knickknacks, all hinting at stories to be told of those they have outlived. With witnesses passing away each year and new structures waiting to be erected over these burial sites, the excavations are truly a race against time, fighting both political amnesia and nature’s complicity in the oblivion. In their quest to rescue war victims from anonymity, forensic scientists assemble excavated bones into skeletons, carry out DNA tests to ascertain identities and hand over the remains to grieving families, who haven’t had closure despite the end of the war and who confess to no longer being able to enjoy landscape without being reminded of what it hides. Baumgartner’s film obscures political and institutional details to focus on the scientific process, offering a fascinating, inspiring picture of the how the abstractions of science eventually coalesce into human stories. Its success lies in finding the right tone and distance necessary for a subject as grave and delicate.

10. Animal Eye (Maxime Martinot, France-Portugal)

Martinot’s funny, free-spirited, quietly radical Animal Eye features a 30-year-old Breton filmmaker discussing his next project with his producer in Lisbon. He isn’t very articulate, but knows that the film will be an “autobiographic animal diary” about his dog Boy. “Films are filled with humans,” he says, “all liars.” Animals, in contrast, are not aware of the camera—or don’t care about it—and as chaotic beings of “pure present,” they evade the signifying operations of the image, emptying it of meaning and intention. As the muddled filmmaker slowly “hands over” the project to his smart, wry producer, the film’s central theme crystallizes: in neither owing anything to imagemakers nor expecting anything from them, the filmed animal offers a way out of the crippling egocentrism of artistic creation. In being just an image, the filmed animal becomes a just image. Animal Eye takes the first tentative steps towards the faint understanding that a “cinema of animals” shouldn’t consist of simply filming the world from their eyes, but filming as them, whatever that might entail. Chaining together clips of dogs from across movie history—subject to sadistic torture, sentimentalism and signification, locked out of the human realm—Martinot’s film embodies a rousing rallying cry on behalf of a “deanthropocentrized” cinema. In its own modest way, Animal Eye marks a milestone in anti-speciesist filmmaking.

Martinot’s funny, free-spirited, quietly radical Animal Eye features a 30-year-old Breton filmmaker discussing his next project with his producer in Lisbon. He isn’t very articulate, but knows that the film will be an “autobiographic animal diary” about his dog Boy. “Films are filled with humans,” he says, “all liars.” Animals, in contrast, are not aware of the camera—or don’t care about it—and as chaotic beings of “pure present,” they evade the signifying operations of the image, emptying it of meaning and intention. As the muddled filmmaker slowly “hands over” the project to his smart, wry producer, the film’s central theme crystallizes: in neither owing anything to imagemakers nor expecting anything from them, the filmed animal offers a way out of the crippling egocentrism of artistic creation. In being just an image, the filmed animal becomes a just image. Animal Eye takes the first tentative steps towards the faint understanding that a “cinema of animals” shouldn’t consist of simply filming the world from their eyes, but filming as them, whatever that might entail. Chaining together clips of dogs from across movie history—subject to sadistic torture, sentimentalism and signification, locked out of the human realm—Martinot’s film embodies a rousing rallying cry on behalf of a “deanthropocentrized” cinema. In its own modest way, Animal Eye marks a milestone in anti-speciesist filmmaking.

Special Mention: Saturn Bowling (Patricia Mazuy, France)

Favourite Films of

2021 • 2020 • 2019 • 2015 • 2014 • 2013 • 2012 • 2011 • 2010 • 2009