With only a handful of posts published, the blog pretty much went into hibernation this year. While 2024 was full of opportunities, encounters and discoveries that I am immensely grateful for, it was also, personally, a year of greater flight from the world, including the world of cinema in some ways. I cut myself off more and more from the news cycle and social media for sanity’s sake, which has meant that I’m woefully unaware of, among other things, what’s making waves in the awards circuit and what the “important” films of this year are. At a glance, I don’t recognize most of the titles featured on major year-end lists.

At the same time, I find myself more embedded than ever in the professional world of cinema, working with different film festivals in various capacities, minor or otherwise. While I haven’t been able to write and translate as much as I would love to, I’ve found myself increasingly involved in programming and selecting films. This has had, I think, considerable consequence on the way I watch and write about cinema.

Firstly, the majority of the titles I saw this year were works-in-progress (WIP): projects in post-production, without CGI, colour grading, sound-mix, and even some shots or subplots. Such a ‘pre-natal’ view of films tends to put the viewer in a state of disenchantment in which one becomes too aware of the strings being pulled: actors simulating shock, disgust or joy in front of blank screens, interacting with inexistant elements of the décor, suspended on ropes, drowned in ambient noise or struggling to convey an emotion, hoping that the music will do that rest.

Over time, watching such volumes of unfinished films could also make a year-end list like this a hassle, since it I have to constantly check whether a particular WIP that I liked last year has released this year or is still waiting for a premiere. More crucially, such lists will likely be even more aleatory and subject to the vagaries of my viewing assignments rather than, as in the past, seeking to take into consideration, even if nominally, consensus titles and popular favourites.

The bulk of my writing this year has also been of a private nature, tied to the programming work. Destined for a handful of known people within a festival, instead of a wider readership online, the texts have undergone a change in kind. If they have gained in freedom and concision, they have lost the rigour and rhetorical force that comes with public writing. I can’t yet imagine what kind of impact this might have on my instincts – and mental capacity to engage with films – in the long run.

All this preamble to say that this blog may continue to remain inactive in the coming year(s). While that is nothing new – it was already in cold storage along with my cinephilia from 2016 to 2019 – it does feel different not to be identifying primarily as a critic/translator anymore. Interesting times ahead.

Here’s wishing a happy new year.

1. The Adamant Girl (P.S. Vinothraj, India)

When Kottukkaali (The Adamant Girl) released in theatres, miraculously, in August in Tamil Nadu, it was accompanied by substantial popular backlash. Admittedly, Kottukkaali is a tough-minded work, one that is perhaps harder to instantly ‘like’ than Vinothraj’s debut Koozhangal (2021). Like the latter, it makes us intimate with the unbridled rage of its male lead, but it does so without the emotional cushion of a child’s perspective. Instead, the film performs a high-wire act, tensely balancing different, conflicting points of views towards its protagonist, Meena, a young lovelorn girl deemed possessed and taken to a local godman for exorcism by her extended family that includes Pandi, the hot-tempered cousin she is betrothed to. While the entourage constantly discusses what is to be done about the girl, Meena herself remains resolutely mute, her silence conveying both defiance and stoic resignation. Kottukkaali explores both the horrific dimensions of this pervasive practice and the subversive space of resistance it offers to the ‘possessed’, temporarily immune from secular violence. At once sophisticated and utterly simple, Kottukkaali respects its audience’s imagination and intelligence while withholding nothing from them. In its formal wit, its trenchant social portraiture and its uncompromising humanism, it represents a significant leap forward for Vinothraj. [World Premiere: Berlin International Film Festival]

When Kottukkaali (The Adamant Girl) released in theatres, miraculously, in August in Tamil Nadu, it was accompanied by substantial popular backlash. Admittedly, Kottukkaali is a tough-minded work, one that is perhaps harder to instantly ‘like’ than Vinothraj’s debut Koozhangal (2021). Like the latter, it makes us intimate with the unbridled rage of its male lead, but it does so without the emotional cushion of a child’s perspective. Instead, the film performs a high-wire act, tensely balancing different, conflicting points of views towards its protagonist, Meena, a young lovelorn girl deemed possessed and taken to a local godman for exorcism by her extended family that includes Pandi, the hot-tempered cousin she is betrothed to. While the entourage constantly discusses what is to be done about the girl, Meena herself remains resolutely mute, her silence conveying both defiance and stoic resignation. Kottukkaali explores both the horrific dimensions of this pervasive practice and the subversive space of resistance it offers to the ‘possessed’, temporarily immune from secular violence. At once sophisticated and utterly simple, Kottukkaali respects its audience’s imagination and intelligence while withholding nothing from them. In its formal wit, its trenchant social portraiture and its uncompromising humanism, it represents a significant leap forward for Vinothraj. [World Premiere: Berlin International Film Festival]

2. Twilight of the Warriors – Walled In (Soi Cheang, Hong Kong)

Decades in the making, Twilight of the Warriors: Walled In, Soi Cheang’s supremely kinetic martial arts epic, forges a double legend linking the mythical past of the now-demolished Walled City and a vibrant, close-knit Hong Kong of the eighties before the island’s handover to China. In gargantuan sets of stunning detail, the film recreates the ramshackle complex, not just the densely packed mass of its buildings, but also the thriving economy and community of this dizzyingly vertical ghetto. Desperate to evade the police and gang members, scrappy refugee Lok enters the Kowloon Walled City, a seedy, crime-ridden slum complex exempt from the law and run under the benign authority of Cyclone. Lok’s diligence and fighting spirit attract the paternal Cyclone, but when the young man’s past comes to light, the very existence of the Walled City is endangered. A masterclass in modern cinematic action, the film conceives its astonishing martial-arts sequences in a close co-choreography of camera movement, continuity editing, geometric décor and athletic performers, the whole presented at human scale and close to real-time speed. With every shot having the force of an abstract painting in its dynamic sight lines, Walled In delivers a sweeping, sensational spectacle. [WP: commercial release]

Decades in the making, Twilight of the Warriors: Walled In, Soi Cheang’s supremely kinetic martial arts epic, forges a double legend linking the mythical past of the now-demolished Walled City and a vibrant, close-knit Hong Kong of the eighties before the island’s handover to China. In gargantuan sets of stunning detail, the film recreates the ramshackle complex, not just the densely packed mass of its buildings, but also the thriving economy and community of this dizzyingly vertical ghetto. Desperate to evade the police and gang members, scrappy refugee Lok enters the Kowloon Walled City, a seedy, crime-ridden slum complex exempt from the law and run under the benign authority of Cyclone. Lok’s diligence and fighting spirit attract the paternal Cyclone, but when the young man’s past comes to light, the very existence of the Walled City is endangered. A masterclass in modern cinematic action, the film conceives its astonishing martial-arts sequences in a close co-choreography of camera movement, continuity editing, geometric décor and athletic performers, the whole presented at human scale and close to real-time speed. With every shot having the force of an abstract painting in its dynamic sight lines, Walled In delivers a sweeping, sensational spectacle. [WP: commercial release]

3. Who Cares? (Alexe Poukine, Belgium)

Kneel down, and you will believe, said Pascal. In That Which Does Not Kill (2019), Alexe Poukine had actors re-enact another person’s reason-defying testimony of sexual assault, allowing them to find pathways to empathy through text, performance and the spoken word. Deeping this line of inquiry, Who Cares? looks at a soft-skill course in Lausanne, Switzerland, in which trainee doctors and caregivers engage in simulated conversations with actors playing patients, with the goal of being more mindful of patients’ feelings during diagnosis. At the heart of this course aimed at humanising healthcare is the belief that empathy, like other qualities, can be learnt through performance, repetition and critical feedback. Even as it brings us close to this view, Poukine’s film qualifies it, presenting us another theatre-based training session in which real medical staff grapple with their professional frustrations born of difficult working conditions, revealing how individual goodwill finds its limits in institutional realities. Like Harun Farocki’s best work, Who Cares? zeroes in on the niche rituals of a highly specialized field, only to lay bare broader civilization and historical undercurrents; in this case, the contradictions generated by the high premium placed on individual wellbeing in western societies. [WP: Cinéma du Réel]

Kneel down, and you will believe, said Pascal. In That Which Does Not Kill (2019), Alexe Poukine had actors re-enact another person’s reason-defying testimony of sexual assault, allowing them to find pathways to empathy through text, performance and the spoken word. Deeping this line of inquiry, Who Cares? looks at a soft-skill course in Lausanne, Switzerland, in which trainee doctors and caregivers engage in simulated conversations with actors playing patients, with the goal of being more mindful of patients’ feelings during diagnosis. At the heart of this course aimed at humanising healthcare is the belief that empathy, like other qualities, can be learnt through performance, repetition and critical feedback. Even as it brings us close to this view, Poukine’s film qualifies it, presenting us another theatre-based training session in which real medical staff grapple with their professional frustrations born of difficult working conditions, revealing how individual goodwill finds its limits in institutional realities. Like Harun Farocki’s best work, Who Cares? zeroes in on the niche rituals of a highly specialized field, only to lay bare broader civilization and historical undercurrents; in this case, the contradictions generated by the high premium placed on individual wellbeing in western societies. [WP: Cinéma du Réel]

4. The Damned (Roberto Minervini, Italy/USA)

In 1862, during the American Civil War, a troop of Union soldiers is sent to survey the uncharted territories of the West. The young men only have a vague understanding of the reasons for the war, but have their own motivations for donning the uniform. They bide their time, play cards and baseball, and engage in occasional skirmishes against a looming, largely invisible enemy. In his first fictional feature, Minervini forges a spare, brooding Western featuring the rural White southerners who populated his documentaries on backwoods America. Their dialect, diction and body language are modern, and this deliberate anachronism lends the film the texture of a filmed performance. In casting marginalized, stereotyped individuals as Union soldiers and placing them at the very origin of the creation of the United States, Minervini monumentalizes them in the vein of Straub-Huillet’s peasants-turned-gods. At the same time, the counter-casting obliges the non-actors to creatively participate in a founding myth that is very different from the “lost cause” narrative dear to the South. The result is a kind of Lehrstück for both the participants and the audience, a vital gesture of bridge-building in a house that finds itself divided once more. [WP: Cannes International Film Festival]

In 1862, during the American Civil War, a troop of Union soldiers is sent to survey the uncharted territories of the West. The young men only have a vague understanding of the reasons for the war, but have their own motivations for donning the uniform. They bide their time, play cards and baseball, and engage in occasional skirmishes against a looming, largely invisible enemy. In his first fictional feature, Minervini forges a spare, brooding Western featuring the rural White southerners who populated his documentaries on backwoods America. Their dialect, diction and body language are modern, and this deliberate anachronism lends the film the texture of a filmed performance. In casting marginalized, stereotyped individuals as Union soldiers and placing them at the very origin of the creation of the United States, Minervini monumentalizes them in the vein of Straub-Huillet’s peasants-turned-gods. At the same time, the counter-casting obliges the non-actors to creatively participate in a founding myth that is very different from the “lost cause” narrative dear to the South. The result is a kind of Lehrstück for both the participants and the audience, a vital gesture of bridge-building in a house that finds itself divided once more. [WP: Cannes International Film Festival]

5. Kiss Wagon (Midhun Murali, India)

In a film culture where a project shepherded through half-a-dozen funding bodies, script labs, residencies and international co-producers is deemed ‘indie’, here is a film that obliges us to recalibrate our notions of what independent cinema could mean. The credit roll of Midhun Murali’s animated digital saga is entirely split between the filmmaker, his creative partner Greeshma Ramachandran and the voice actor Jicky Paul. Kiss Wagon charts the sprawling odyssey of Isla, a cocaine-addled courier girl, who leads a disengaged life in a police state under the sway of a powerful, puritanical cult. When she is entrusted by a mysterious client to deliver a kiss to an encrypted address, Isla finds herself on the wrong side of a massive military-theocratic conspiracy. Narrated in a mix of tongues real and invented, using a range of animation techniques classical and cutting-edge, Midhun’s film tells a mythical tale of the planetary struggle between the darkness of religious dogma and the light of cinema. A revisionist testament in four chapters, Kiss Wagon is an epic ballad of a paradise lost and regained; regained not through the force of institutionalized virtue, but through the agitations of outsiders, non-conformists, misfits and weirdos. A homemade cinematic A-bomb, delivered with a kiss. [WP: International Film Festival Rotterdam]

In a film culture where a project shepherded through half-a-dozen funding bodies, script labs, residencies and international co-producers is deemed ‘indie’, here is a film that obliges us to recalibrate our notions of what independent cinema could mean. The credit roll of Midhun Murali’s animated digital saga is entirely split between the filmmaker, his creative partner Greeshma Ramachandran and the voice actor Jicky Paul. Kiss Wagon charts the sprawling odyssey of Isla, a cocaine-addled courier girl, who leads a disengaged life in a police state under the sway of a powerful, puritanical cult. When she is entrusted by a mysterious client to deliver a kiss to an encrypted address, Isla finds herself on the wrong side of a massive military-theocratic conspiracy. Narrated in a mix of tongues real and invented, using a range of animation techniques classical and cutting-edge, Midhun’s film tells a mythical tale of the planetary struggle between the darkness of religious dogma and the light of cinema. A revisionist testament in four chapters, Kiss Wagon is an epic ballad of a paradise lost and regained; regained not through the force of institutionalized virtue, but through the agitations of outsiders, non-conformists, misfits and weirdos. A homemade cinematic A-bomb, delivered with a kiss. [WP: International Film Festival Rotterdam]

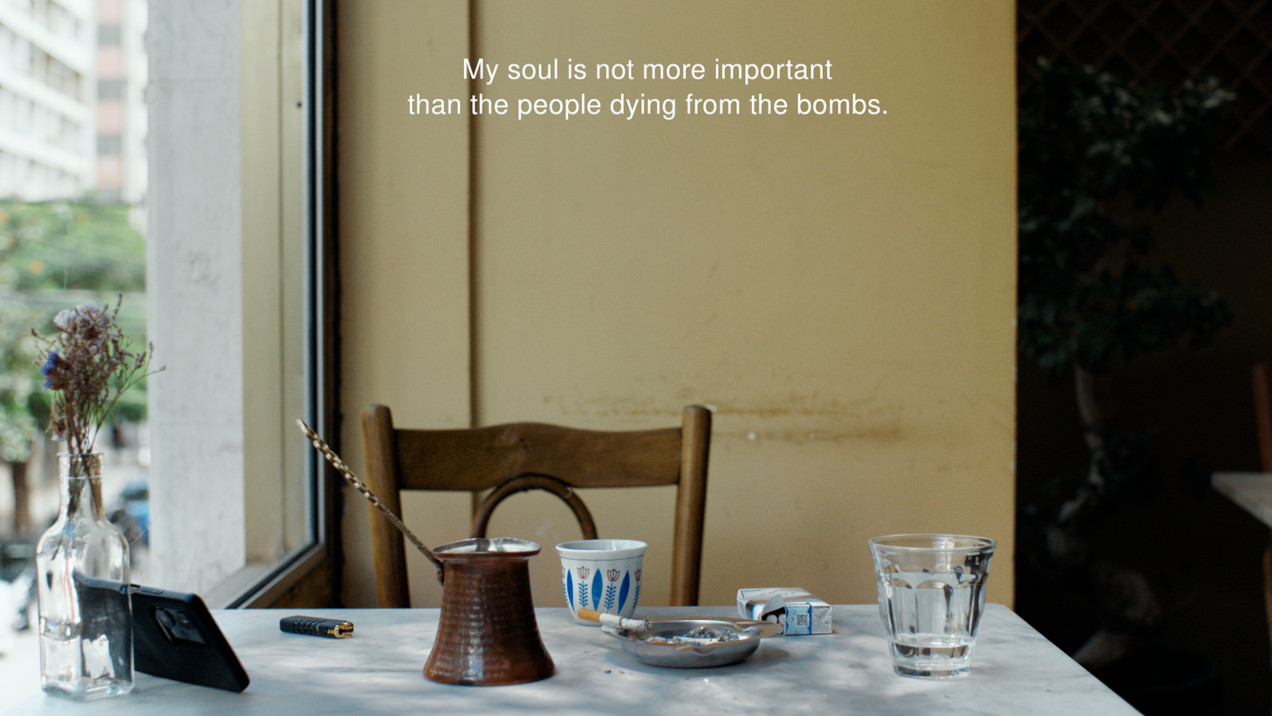

6. We Are Inside (Farah Kassem, Lebanon)

The family documentary may currently be the most shopworn, convention-ridden genre in non-fiction film. But Farah Kassem’s three-hour-long domestic epic We Are Inside represents a sweeping personal work that makes a strong case for its continued existence. Following the demise of her mother, thirty-something European resident Kassem returns home to Tripoli, Lebanon, after fifteen years of absence to live with her cantankerous octogenarian poet-father. She spends her time learning Arabic from him, cutting his hair, tending to his wounds, sorting his medicine, driving him around and, most entertainingly, participating in his old boys’ meetups. Poetry becomes both an heirloom the filmmaker inherits and the means through which she concretises the daughterly bond. As the world outside falls apart, with Lebanon experiencing one shock after another, the film turns into a rumination on the role of artmaking during times of political crises, the artist oscillating between the pursuit of beauty and the reflection of truth, between the personal and the political, between inside and the outside. An instructive companion piece to Abbas Fahdel’s Tales of the Purple House (2022), We Are Inside offers a rich, funny and moving work that deserves wider viewing. [WP: Visions du Réel]

The family documentary may currently be the most shopworn, convention-ridden genre in non-fiction film. But Farah Kassem’s three-hour-long domestic epic We Are Inside represents a sweeping personal work that makes a strong case for its continued existence. Following the demise of her mother, thirty-something European resident Kassem returns home to Tripoli, Lebanon, after fifteen years of absence to live with her cantankerous octogenarian poet-father. She spends her time learning Arabic from him, cutting his hair, tending to his wounds, sorting his medicine, driving him around and, most entertainingly, participating in his old boys’ meetups. Poetry becomes both an heirloom the filmmaker inherits and the means through which she concretises the daughterly bond. As the world outside falls apart, with Lebanon experiencing one shock after another, the film turns into a rumination on the role of artmaking during times of political crises, the artist oscillating between the pursuit of beauty and the reflection of truth, between the personal and the political, between inside and the outside. An instructive companion piece to Abbas Fahdel’s Tales of the Purple House (2022), We Are Inside offers a rich, funny and moving work that deserves wider viewing. [WP: Visions du Réel]

7. Wikiriders (Clara Winter, Mi(gu)el Ferràez, Megan Marsh, Mexico/Germany)

If you ever wondered where the missing Human Surge sequel was, here is a less punishing proposition. A super-chill hangout film, Wikiriders centres on a multilingual band of three friends – one speaking English, the other Spanish and the third German, interchangeably and out of lip sync – who undertake a road trip from Mexico to the USA in search of a powerful (fictional?) family that has had an outsized influence on the history of the two countries. The trio may be navigating the Mexican landscape, but they are also virtual surfers, following the rabbit hole of Wikipedia edits about/by the members of the family. Wikiriders takes the epistemological processes of the internet as inspiration for its structure, hopping from one narrative tab to another, featuring memes for characters and making maps of meaning out of digital babel, while also raising pertinent questions about the rewriting of popular history and the resistance to it through voluntary international collaboration. Imbibing the spirit of the Nouvelle Vague as well as the road movies of Monte Hellman, Ron Rice and Wim Wenders, Wikiriders embraces the fact that it’s largely discovered on the editing table. Fun, experimental and very accessible. [WP: Berlin Critics’ Week]

If you ever wondered where the missing Human Surge sequel was, here is a less punishing proposition. A super-chill hangout film, Wikiriders centres on a multilingual band of three friends – one speaking English, the other Spanish and the third German, interchangeably and out of lip sync – who undertake a road trip from Mexico to the USA in search of a powerful (fictional?) family that has had an outsized influence on the history of the two countries. The trio may be navigating the Mexican landscape, but they are also virtual surfers, following the rabbit hole of Wikipedia edits about/by the members of the family. Wikiriders takes the epistemological processes of the internet as inspiration for its structure, hopping from one narrative tab to another, featuring memes for characters and making maps of meaning out of digital babel, while also raising pertinent questions about the rewriting of popular history and the resistance to it through voluntary international collaboration. Imbibing the spirit of the Nouvelle Vague as well as the road movies of Monte Hellman, Ron Rice and Wim Wenders, Wikiriders embraces the fact that it’s largely discovered on the editing table. Fun, experimental and very accessible. [WP: Berlin Critics’ Week]

8. Kajolrekha (Giasuddin Selim, Bangladesh)

Adapted from a medieval folk ballad from the Mymensingh region of present-day Bangladesh, Giasuddin Selim’s sumptuous, widescreen musical fairytale Kajolrekha is a melodrama in the etymological sense of the word: music + drama. The film employs nearly twenty songs, sung by characters and narrators alike, to advance the plot, deepen emotions, comment on actions and, at points, critically distance the viewer from the story. Bankrupted by his gambling addiction, merchant Dhwaneshwer is given a second chance when a mysterious monk gifts him a soothsaying bird. The bird restores Dhwaneshwer’s lost glory, but also instructs him to exile his 13-year-old daughter Kajolrekha. Forced to lead a life of anonymity and hardship, Kajolrekha perseveres until the tides turn, even if it means paying a heavy price. Selim’s actors adopt a precisely stylized repertoire of theatrical gestures, postures and voice tones to express the essence of their roles, be they slaves, merchants or aristocrats. This conscious revival of a classical narrative tradition isn’t carried out ironically, but with a modernist sense of the latent possibilities of a lost artform. Moving tragically flawed characters across a perfectly orchestrated chessboard of fate and destiny, Kajolrekha reaffirms the inevitability of a just and benevolent world. [WP: commercial release]

Adapted from a medieval folk ballad from the Mymensingh region of present-day Bangladesh, Giasuddin Selim’s sumptuous, widescreen musical fairytale Kajolrekha is a melodrama in the etymological sense of the word: music + drama. The film employs nearly twenty songs, sung by characters and narrators alike, to advance the plot, deepen emotions, comment on actions and, at points, critically distance the viewer from the story. Bankrupted by his gambling addiction, merchant Dhwaneshwer is given a second chance when a mysterious monk gifts him a soothsaying bird. The bird restores Dhwaneshwer’s lost glory, but also instructs him to exile his 13-year-old daughter Kajolrekha. Forced to lead a life of anonymity and hardship, Kajolrekha perseveres until the tides turn, even if it means paying a heavy price. Selim’s actors adopt a precisely stylized repertoire of theatrical gestures, postures and voice tones to express the essence of their roles, be they slaves, merchants or aristocrats. This conscious revival of a classical narrative tradition isn’t carried out ironically, but with a modernist sense of the latent possibilities of a lost artform. Moving tragically flawed characters across a perfectly orchestrated chessboard of fate and destiny, Kajolrekha reaffirms the inevitability of a just and benevolent world. [WP: commercial release]

9. Sleep #2 (Radu Jude, Romania)

Culling from four seasons’ worth of footage from EarthCam’s live-stream of Andy Warhol’s tomb in Pennsylvania, Radu Jude fashions a spiritual sequel to Warhol’s blockbuster of boredom, Sleep (1964). Where the older film turned the dormant body of Warhol’s lover into a monument comparable to the Empire State Building, Jude’s film, almost equally unwatchable, fixates on Warhol’s own body repurposed into a public monument. As fans and curious passersby click pictures, pose flowers, decorate it with Campbell soup cans and even organize parties around it, the artist’s tomb becomes something like a collective work of art, vested with a social signification. A modern cinematic readymade, Jude’s desktop documentary crafts an unassuming essay on celebrity and fame, entirely in line with Warhol’s work. What happens when television ceases to be the arbiter of mass taste and simply becomes the condition of everyday life? Not fifteen minutes, but the possibility of eternal fame? Just as the visitors bestow the grave with meanings it doesn’t possess in itself, the act of watching the live-stream turns out to be the means by which operational images become aesthetic objects. Critically interrogating spectatorship, Jude’s fascinating film affirms the triumph of life over eternal sleep. [WP: Locarno International Film Festival]

Culling from four seasons’ worth of footage from EarthCam’s live-stream of Andy Warhol’s tomb in Pennsylvania, Radu Jude fashions a spiritual sequel to Warhol’s blockbuster of boredom, Sleep (1964). Where the older film turned the dormant body of Warhol’s lover into a monument comparable to the Empire State Building, Jude’s film, almost equally unwatchable, fixates on Warhol’s own body repurposed into a public monument. As fans and curious passersby click pictures, pose flowers, decorate it with Campbell soup cans and even organize parties around it, the artist’s tomb becomes something like a collective work of art, vested with a social signification. A modern cinematic readymade, Jude’s desktop documentary crafts an unassuming essay on celebrity and fame, entirely in line with Warhol’s work. What happens when television ceases to be the arbiter of mass taste and simply becomes the condition of everyday life? Not fifteen minutes, but the possibility of eternal fame? Just as the visitors bestow the grave with meanings it doesn’t possess in itself, the act of watching the live-stream turns out to be the means by which operational images become aesthetic objects. Critically interrogating spectatorship, Jude’s fascinating film affirms the triumph of life over eternal sleep. [WP: Locarno International Film Festival]

10. Journey of the Shadows (Yves Netzhammer, Switzerland)

Once living a life of harmony in a dystopian world, two bipedal figures – humanlike but featureless, genderless – fall out under the influence of a mystical pet fish. One of them perishes, and the other embarks on an odyssey across the seas, intermittently led by a book and a candle. After countless catastrophes, this wandering being washes ashore on a pristine island, where it tries to overcome its loneliness, alas in vain. This probably isn’t what happens in Swiss multimedia artist Yves Netzhammer’s wordless, mind-bending first feature, in which identities, relations and situations are in such a flux as to resist any kind of linear synopsis. Where traditional animation advances evermore towards a utopian combination of naturalism and expressivity, Journey operates at a zero degree of digital image-making, dealing in primitive figures, bald volumes, harsh lighting, rudimentary physics, sickeningly unmodulated colours, oneiric movements, and an oppressive clarity of visual field recalling Dali or Magritte. At its best, Netzhammer’s abstract film has the subversive, Kafkaesque quality of Central European animation from the 1960s and ‘70s. Defying binaries of nature/civilization, human/technology, organic/synthetic, Journey crafts a deeply disturbing meditation on freedom, creation and self-discovery whose brutality shocks all the more in a universe so unreal. [WP: International Film Festival Rotterdam]

Once living a life of harmony in a dystopian world, two bipedal figures – humanlike but featureless, genderless – fall out under the influence of a mystical pet fish. One of them perishes, and the other embarks on an odyssey across the seas, intermittently led by a book and a candle. After countless catastrophes, this wandering being washes ashore on a pristine island, where it tries to overcome its loneliness, alas in vain. This probably isn’t what happens in Swiss multimedia artist Yves Netzhammer’s wordless, mind-bending first feature, in which identities, relations and situations are in such a flux as to resist any kind of linear synopsis. Where traditional animation advances evermore towards a utopian combination of naturalism and expressivity, Journey operates at a zero degree of digital image-making, dealing in primitive figures, bald volumes, harsh lighting, rudimentary physics, sickeningly unmodulated colours, oneiric movements, and an oppressive clarity of visual field recalling Dali or Magritte. At its best, Netzhammer’s abstract film has the subversive, Kafkaesque quality of Central European animation from the 1960s and ‘70s. Defying binaries of nature/civilization, human/technology, organic/synthetic, Journey crafts a deeply disturbing meditation on freedom, creation and self-discovery whose brutality shocks all the more in a universe so unreal. [WP: International Film Festival Rotterdam]

Special Mention: Dahomey (Mati Diop, Senegal/Benin/France)

Favourite Films of

2023 • 2022 • 2021 • 2020 • 2019 • 2015

2014 • 2013 • 2012 • 2011 • 2010 • 2009