[From Luc Moullet’s monograph Cecil B. DeMille: The Emperor of Mauve (2012, Capricci). See Table of Contents]

Joan the Woman (1916): first flagellation in DeMille’s work.

One of the most evident, and strangest, characteristics of his work is its sadomasochism—something that is as present as the theme of water in Renoir, the opulent women dear to Fellini, the port towns in Demy or Hitchcock’s suspense. This clearly proves, if proof was ever needed, that DeMille is an auteur.

It all began in 1915, with the first truly interesting films by our filmmaker, and continued without any notable interruption until the last opus in 1956.

Delight Warren (The Unafraid) is threatened with the worst torture if she does not sign a cheque.

The Cheat revolves around a rich Japanese man who brands a socialite guilty of rejecting him after he had lent her a large sum of money. According to him, one doesn’t go without the other. You don’t see this barbaric act in this understated film where everything works on evocation, the unsaid. But we do see what precedes and follows it, and everything around it. This understatement is obviously more powerful than if DeMille had filmed it all. It remains within the limits of good taste, and we can imagine everything…

DeMille shot The Cheat by day, and at night, he directed The Golden Chance, in which young Mary Denby is whipped by her alcoholic husband, who unjustly accuses her of all vices. The film is set in a contemporary America, but the action recalls the melodramatic situations of London-based novels, particularly the work of Charles Dickens (Nicholas Nickelby, Oliver Twist, David Copperfield), where the whipped child constitutes a leitmotif.

It was Joan the Woman the following year, where the heroine is threatened with being interrogated by the English, which is in keeping with historical reality. But there is also this astonishing scene where a French peasant woman, accused of collaborating with French troops resisting the invaders, is suddenly stripped naked by His Majesty’s soldiers and severely flogged. This is a kind of action that has not been recorded in history, and which doesn’t seem very credible. Moreover, the filmed episode has little to do with Joan of Arc. We find no such scene in any of the many films made on the Maiden of Domrémy. It should be noted that, to avoid the charge of indecency, DeMille had taken the precaution of casting a very flat-chested actress in the role.

In Why Change Your Wife (1919), the heroine tries to disfigure her romantic rival with vitriol. It isn’t vitriol, in fact, but eyewash intended to frighten the girl, and to thrill the audience with this unsettling threat.

To this, I would add the paw of the lion on the body of an unconscious Gloria Swanson in Male and Female (same year).

The whip, decidedly a central prop in our auteur’s work, appears again in the two versions of The Ten Commandments (1923 and 1956), since it was frequently used in the Egypt of the Pharaohs, and especially in The Road to Yesterday (1925), where the English lord Ken whips his rival to death, just after the gypsy woman is condemned to the stake.

The Plainsman (1936): Calamity Jane (Jean Arthur) never lets go of her whip.

The King of Kings (1927) retraces the martyrdom of Christ in all its stages. There is, of course, a masochist component in the whole of Christian universe. In Jesus’s journey, we can see the itinerary of a man who did everything possible in order to be tortured and crucified. Had Pontius Pilate pardoned him, he would have been really annoyed and couldn’t have justifiably claimed the role of a glorious martyr. And his example led several Christians to try to imitate him. We would be justified in wondering whether it isn’t the Christian impulse that drove DeMille towards sadomasochism.

The Godless Girl (1928) is set in a juvenile prison, where, for more than one minute, the evil guard subjects the handsome, rebellious Hathaway to a powerful jet of ice-cold water. And when the young lovers meet and try to kiss each other from either side of the fence, he unleashes a strong electric current through the barbed wire so that the heroine cannot detach herself from the fence and burns her hand: a shot reveals a smoking cross imprinted on her palm (a cross again).

I almost forgot the Tsarist officer in The Volga Boatman (1926) who orders a young boatman to shine his boots, which he has slightly soiled by accident, and deeming his speech insolent, whips him on the face. Already back in The Little American, there was the German officer who orders poor Mary Pickford to remove his boots, which isn’t an easy job.

The Sign of the Cross is perhaps the one film by our auteur that goes the furthest in this domain. There is firstly the child that the Romans tie to a rope and lower into a pit with hellfire (a torture that Joan of Arc was threatened with too) so that he confesses where the Christians meet.

There is then the pleasure of the viewers in the arena—father, mother and son—who try to get the best seats possible and bet on the surviving gladiator. A pleasure mixed with dread before the martyrdom of Christians (a situation that is repeated, in a minor way, at the temple of the Philistines at the end of Samson and Delilah): we are spared no detail (except in the redacted version at the request of the censors, who nevertheless let go of shots of dykes and boy toys). The highlight is this ravishing starlet in a bikini tied up in front of a menacing crocodile. These are brilliant, very powerful scenes, especially since the visuals are sumptuous, but which make The Sign of the Cross look like a sick film.

All through The Plainsman (1936) and Union Pacific (1939), the beautiful Jean Arthur and Akim Tamiroff wield a menacing whip, which attacks objects around people, but never the people themselves. The Hays Code of 1934 was here.

At the beginning of North West Mounted Police (1940), it’s Paulette Goddard, a rather wild young girl, who is spanked by Tamiroff. She will be spanked again, with the relative protection of her pretty rich heiress costume, by the dandy Ray Milland, who finds her too capricious, at the beginning of Reap the Wild Wind (1941). In Unconquered (1946), we witness the preparations for the flogging of the same Paulette Goddard, who is decidedly used to corporal punishment, a torture that is called off at the last second. For the sadomasochistic audience, it’s the cracking of the whip and the concept of flogging that counts (and allows it to imagine the foreseeable consequences with delight) as much as the physical act, just as it was the idea of disfiguration with vitriol (which doesn’t take place) that marks the viewer’s mind (Why Change Your Wife). This avoids the reproach of the censors and the restrictions pertaining to children.

A novelty: at the end of Samson and Delilah (1949), the whipper Delilah and the whipped Samson are fully agreed on the use of the prop. She even apologizes to him for the pain she is about to inflict on him. It is part of the plan laid by Samson, who, as the viewers at the temple are fooled by this stratagem, then seizes the whip from Delilah, the latter leading him to the pillars of the building.

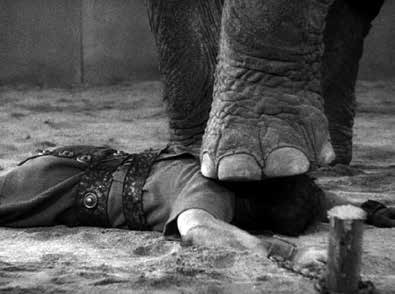

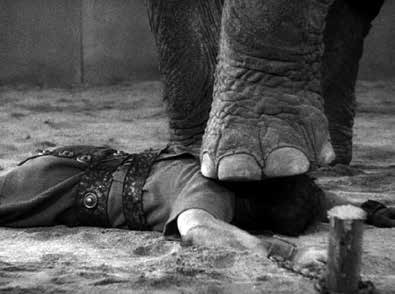

There is a very interesting variation of this in the middle of The Greatest Show on Earth (1951): the animal trainer Lyle Bettger, jealous of the special attention that his sweetheart, the beautiful Gloria Graham, pays to the circus director Charlton Heston, blackmails her during an act, by letting her remain under the elephant’s heavy foot for longer than expected: a guiding gesture from the trainer would be enough for the beast to crush her pretty face. In The Sign of the Cross, the animal brings down its foot for good.

I’ve saved the best for the last: Cleopatra, where the sadistic ritual is intimately linked to sexuality. To seduce Mark Antony, Cleopatra presents him with an astonishing spectacle where seductive nymphs, fished out from the sea in large nets (a woman was already fished out with a bait in Old Wives for New), come out of shells that look like vulvas, to perform lascivious dances, surrounded by the dance master’s whip and circles of fire that he raises around them and through which they move. It’s a delirious spectacle that attests to great virtuosity on the part of our filmmaker, and a rather implausible one at that: it’s hard to imagine a woman who, in order to win the heart of her enemy, organizes such a macho show focused on other women.

In Cleopatra again, during the Battle of Actium sequence, there is this very oppressive shot of a chariot’s cogwheel crushing a soldier’s face.

The reader will perhaps forgive me for forgetting other scenes of the kind, which are often brilliant and rather nauseating, the two adjectives being linked indissolubly.

The Sign of the Cross (1932): gladiators and Christians in the arena.

This psychopathia sexualis is well in line with the image Cecil DeMille fashioned for himself: with jodhpurs and a baton in the hand (like his mentor David Belasco), he had all the makings of the perfect sadistic grandmaster.

We may wonder, is this whole arsenal there to please a public fond of sadomasochistic rituals? Or does it correspond to a personal need? I’m tempted to answer with the latter option. In fact, it all began as early as 1915, at a time when the film viewer’s sadistic needs were neither known nor exploited. One had to wait until the advent of the horror film, Tod Browning and James Whale, in the years 1925-1930, and then the actor Burt Lancaster, the most masochist of all, to find a comparison. In literature, Lovecraft himself comes after DeMille. One would even be justified in thinking that DeMille may have furnished ideas to masters of horror such as Tod Browning or James Whale. It was perhaps also that the public success of these scenes encouraged DeMille to persevere.

Why? Why? It’s not the essayist’s role to discuss this subject. Apart from Christian influence, which I’ve already alluded to, it should be noted that C.B.’s sadism is often exercised on women. And he was a frustrated man, at least during his youth: bald at a young age, he looks like the typical image of a small-time accountant in his photographs. And after 1914 and her miscarriage, his wife, for medical reasons and perhaps because she wasn’t interested in it, refused sex, a situation that seems to have lasted for the last forty-five years of their marriage. To be sure, our man made up for it elsewhere, after he achieved success and fortune. But this situation must have been hard for him. It reminds us of the scene in The Road to Yesterday where Ken tries to axe his way through the door of his wife’s bedroom. It’s a situation that must have left behind a mark, a desire for revenge, a recourse to deviant practices… But frustration can also be very fruitful for an artist: the situation of the DeMille couple is the same as that of the Faulkner couple.

Let us not forget a consistent foot (and shoe) fetish, as evidenced by Old Wives for New, Don’t Change Your Husband, Male and Female, Forbidden Fruit, The Affairs of Anatol, Feet of Clay, The Volga Boatman, Wassell and, of course, The Greatest Show on Earth, among others from 1918 to 1951.