Shijie (The World, 2004)

If there is a film that perfectly sums up the state and outlook of the third world in the first decade of the new century, it has to be Jia Zhang-Ke’s The World (2004), first of the director’s film to be made with official consent. The very premise and setting of the film – a bunch of youngsters working a world park where you can witness life-size replicas of wonders from across the world – provide us with the various undercurrents that characterize the film without being ostentatious. Much like the previous Jia films, the people in The World are terribly out of sync with the environment surrounding them. This is a land where the terrible distances of the real world are pruned down to a few miles, yet the distance between individuals has increased manifold (The cramped and decrepit dressing rooms provide a counterpoint to the grandeur of the park’s front end). This is a zone which enables one to fulfill one’s desire to escape into a whole new world, yet one has to lose every shred of his/her individuality to do so (One of the early shots shows us a bunch of uniformed workers who don’t appear much different from the props they are carrying). This idea of one’s identity being stripped off, layer by layer, is built into the whole structure of the film. Dialects are normalized, costumes are changed by the minute and passports are confiscated. One of the characters towards the end tells: “It’s nice being in someone else’s home” – a delusion that seems to be common to all the residents of this synthetic world.

If there is a film that perfectly sums up the state and outlook of the third world in the first decade of the new century, it has to be Jia Zhang-Ke’s The World (2004), first of the director’s film to be made with official consent. The very premise and setting of the film – a bunch of youngsters working a world park where you can witness life-size replicas of wonders from across the world – provide us with the various undercurrents that characterize the film without being ostentatious. Much like the previous Jia films, the people in The World are terribly out of sync with the environment surrounding them. This is a land where the terrible distances of the real world are pruned down to a few miles, yet the distance between individuals has increased manifold (The cramped and decrepit dressing rooms provide a counterpoint to the grandeur of the park’s front end). This is a zone which enables one to fulfill one’s desire to escape into a whole new world, yet one has to lose every shred of his/her individuality to do so (One of the early shots shows us a bunch of uniformed workers who don’t appear much different from the props they are carrying). This idea of one’s identity being stripped off, layer by layer, is built into the whole structure of the film. Dialects are normalized, costumes are changed by the minute and passports are confiscated. One of the characters towards the end tells: “It’s nice being in someone else’s home” – a delusion that seems to be common to all the residents of this synthetic world.

Sanxia Haoren (Still Life, 2006)

Still Life (2006), which might be the best film by Jia Zhang-Ke yet, presents two stories sewn together thematically and temporally by two significant pan-and-cut shots. The first of them presents a coal miner, Sanming, from rural China moving to Three Gorges to meet his wife after 17 years and the second one gives us a young woman, Shen Hong, traveling to the same place to meet her husband whom she hasn’t seen for 2 years. Using these two threads connected by the China’s Three Gorges Dam project, Jia examines both the disparities, including that of class (Sanming works at the bottom of the rung while Shen Hong’s husband supervises the project), generation (Sanming’s traditional values are pitted against Shen Hong’s strength and resilience) and gender (Sanming and Shen Hong can be seen as the antithesis to each other’s spouses), and the commonalities that characterize the two different worlds that Sanming and Shen Hong inhabit. The prime motif that permeates Still Life is the destruction of the old and the birth of the new. Sanming yearns to return to the past while Shen Hong runs away from it. Residences are cleared to make way for the dam. English language shows its head regularly. And songs about eternal love play on the soundtrack ironically. Lastly, Jia’s film is also a paean to the marvels of the human body – the body that can create and destroy structures much, much larger than it, the body that is ultimately rendered inconsequential (as underscored by Jia’s striking compositions of man constantly being loaded down by the weight of his own creations) by the national importance of the structures themselves.

Still Life (2006), which might be the best film by Jia Zhang-Ke yet, presents two stories sewn together thematically and temporally by two significant pan-and-cut shots. The first of them presents a coal miner, Sanming, from rural China moving to Three Gorges to meet his wife after 17 years and the second one gives us a young woman, Shen Hong, traveling to the same place to meet her husband whom she hasn’t seen for 2 years. Using these two threads connected by the China’s Three Gorges Dam project, Jia examines both the disparities, including that of class (Sanming works at the bottom of the rung while Shen Hong’s husband supervises the project), generation (Sanming’s traditional values are pitted against Shen Hong’s strength and resilience) and gender (Sanming and Shen Hong can be seen as the antithesis to each other’s spouses), and the commonalities that characterize the two different worlds that Sanming and Shen Hong inhabit. The prime motif that permeates Still Life is the destruction of the old and the birth of the new. Sanming yearns to return to the past while Shen Hong runs away from it. Residences are cleared to make way for the dam. English language shows its head regularly. And songs about eternal love play on the soundtrack ironically. Lastly, Jia’s film is also a paean to the marvels of the human body – the body that can create and destroy structures much, much larger than it, the body that is ultimately rendered inconsequential (as underscored by Jia’s striking compositions of man constantly being loaded down by the weight of his own creations) by the national importance of the structures themselves.

Dong (2006)

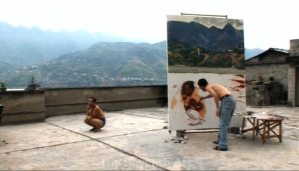

Made as a companion piece to the superior film Still Life, much of whose footage it shares, Dong (2006) sits somewhere alongside The Mystery of Picasso (1956) and The Quince Tree Sun (1992) in the way the director uses another artist – a painter, as is the case with the other two films – to examine the nature of his own work. Dong follows actor and painter Liu Xiao-Dong (who makes a brief appearance in The World) as he completes two of his five-piece paintings – one at the Three Gorges Dam construction site and the other in Bangkok, Thailand. Like Jia, Liu is a realist. Even he prefers to document his subjects from a distance as it provides him “better control and precision”. But when one of his subjects dies in an accident, all he can do is patronize the deceased person’s kids. Is Jia reflecting on the purpose of his own work? Perhaps. Although I believe that there has been an indictment of patriarchy, especially its presence in art, throughout Jia’s body of work, it is most manifest in Dong. In the first segment, Liu admires the body of his naked male models and paints them with utmost enthusiasm while, in Bangkok, he calls his models as “scantily-clad women” and completes his work somewhat dispassionately. We then notice that he is in an alien land not just in geographical terms. Again, it would not be an overstretch to consider much of this satire as self-criticism, given that Jia himself has been unrestrained in marveling the male body in his work, specifically in Still Life.

Made as a companion piece to the superior film Still Life, much of whose footage it shares, Dong (2006) sits somewhere alongside The Mystery of Picasso (1956) and The Quince Tree Sun (1992) in the way the director uses another artist – a painter, as is the case with the other two films – to examine the nature of his own work. Dong follows actor and painter Liu Xiao-Dong (who makes a brief appearance in The World) as he completes two of his five-piece paintings – one at the Three Gorges Dam construction site and the other in Bangkok, Thailand. Like Jia, Liu is a realist. Even he prefers to document his subjects from a distance as it provides him “better control and precision”. But when one of his subjects dies in an accident, all he can do is patronize the deceased person’s kids. Is Jia reflecting on the purpose of his own work? Perhaps. Although I believe that there has been an indictment of patriarchy, especially its presence in art, throughout Jia’s body of work, it is most manifest in Dong. In the first segment, Liu admires the body of his naked male models and paints them with utmost enthusiasm while, in Bangkok, he calls his models as “scantily-clad women” and completes his work somewhat dispassionately. We then notice that he is in an alien land not just in geographical terms. Again, it would not be an overstretch to consider much of this satire as self-criticism, given that Jia himself has been unrestrained in marveling the male body in his work, specifically in Still Life.

Wuyong (Useless, 2007)

Useless (2007) could be considered as a logical extension of Still Life and Dong because it deals with a number of ideas common to those two films. Divided into three segments each of which takes up a unique perspective of the Chinese textile industry, Useless is a dense, meditative essay on production, consumption and function of art. It’s hard not to think of the film as an attempt by Jia to discover his responsibility as an artist and to locate himself within the cinema of his country. Throughout the film there is a battle between aesthetic and functionality of art – a struggle that seeps even into the film’s form – that is manifest in the segments involving mass depersonalized production, custom “auteurist” design catering to the west and smalltime tailoring to suit individual needs. However, Jia’s film does not take a pre-determined stance and shares our indecisiveness. The very fact that the director chooses “impersonal” high-def over the intimacy of film illustrates the complexity underlying the question. Furthermore, Jia’s film also examines the chasm that exists between the oriental and western perceptions of beauty and art. What is a fact of life in China – soiled bodies, dirty and worn out clothes – is considered an exotic, delicately assembled work of art in the west. Female nudity is commonplace in western art whereas male nudity takes its place in the oriental counterpart. When Jia pans his camera over female models getting ready for a show at Paris Fashion Week, one is reminded of the opening shot of Still Life where Jia’s male models sit unclothed in a boat, ready for their performance in the film.

Useless (2007) could be considered as a logical extension of Still Life and Dong because it deals with a number of ideas common to those two films. Divided into three segments each of which takes up a unique perspective of the Chinese textile industry, Useless is a dense, meditative essay on production, consumption and function of art. It’s hard not to think of the film as an attempt by Jia to discover his responsibility as an artist and to locate himself within the cinema of his country. Throughout the film there is a battle between aesthetic and functionality of art – a struggle that seeps even into the film’s form – that is manifest in the segments involving mass depersonalized production, custom “auteurist” design catering to the west and smalltime tailoring to suit individual needs. However, Jia’s film does not take a pre-determined stance and shares our indecisiveness. The very fact that the director chooses “impersonal” high-def over the intimacy of film illustrates the complexity underlying the question. Furthermore, Jia’s film also examines the chasm that exists between the oriental and western perceptions of beauty and art. What is a fact of life in China – soiled bodies, dirty and worn out clothes – is considered an exotic, delicately assembled work of art in the west. Female nudity is commonplace in western art whereas male nudity takes its place in the oriental counterpart. When Jia pans his camera over female models getting ready for a show at Paris Fashion Week, one is reminded of the opening shot of Still Life where Jia’s male models sit unclothed in a boat, ready for their performance in the film.

Er Shi Si Cheng Ji (24 City, 2008)

In 24 City (2008), the latest of Jia’s great works, the director interviews several people all of whom are connected in some way to the prestigious aircraft manufacturing site, Factory-420, in Chengdu city that is now being torn down to make way for a residential complex. What Platform does in the present tense, 24 City does in the past. Each of these accounts so clearly elucidates what is essentially positive and what is not about life in a communist regime. The sheer joy of living as a symbiotic community seems to be counterbalanced by a tendency of individual wishes getting overridden by collective objectives. Throughout, these testimonies effortlessly present how, once, personal tragedies were invariably connected to national decisions and how an individual was able to define himself only with respect to his community (One character even clarifies her name using a city as reference). Furthermore, these accounts also give a vivid picture of the depersonalized and dehumanized way of work at the same factory after China’s cultural reforms in the late seventies. Jia juxtaposes images of the factory being destroyed with the faces of his subjects suggesting the demise of a wholly different way of life and thought. But all is not so sweetly nostalgic about Jia’s film. The set of interviewees consists of a mixture of people who’ve actually been through what they say and actors enacting such people. Are these accounts the absolute truth or are they the comfortable versions of the past concocted by memory with the passage of time? How much of an actor is there in each of these people? Jia, never ever cynical, is content in playing the Godard-ish ethnographer. Brilliant.

In 24 City (2008), the latest of Jia’s great works, the director interviews several people all of whom are connected in some way to the prestigious aircraft manufacturing site, Factory-420, in Chengdu city that is now being torn down to make way for a residential complex. What Platform does in the present tense, 24 City does in the past. Each of these accounts so clearly elucidates what is essentially positive and what is not about life in a communist regime. The sheer joy of living as a symbiotic community seems to be counterbalanced by a tendency of individual wishes getting overridden by collective objectives. Throughout, these testimonies effortlessly present how, once, personal tragedies were invariably connected to national decisions and how an individual was able to define himself only with respect to his community (One character even clarifies her name using a city as reference). Furthermore, these accounts also give a vivid picture of the depersonalized and dehumanized way of work at the same factory after China’s cultural reforms in the late seventies. Jia juxtaposes images of the factory being destroyed with the faces of his subjects suggesting the demise of a wholly different way of life and thought. But all is not so sweetly nostalgic about Jia’s film. The set of interviewees consists of a mixture of people who’ve actually been through what they say and actors enacting such people. Are these accounts the absolute truth or are they the comfortable versions of the past concocted by memory with the passage of time? How much of an actor is there in each of these people? Jia, never ever cynical, is content in playing the Godard-ish ethnographer. Brilliant.

Heshang Aiqing (Cry Me A River, 2008)

Picture Jia repenting for not being completely nostalgic in 24 City and deciding to assuage that guilt with a purely fictional feature. The 20-minute short Cry Me A River (2008) is just that. A group of middle class friends, well in their thirties, meet up, have dinner with one of their professors and talk in pairs about how their lives have been after they went their own ways. This must be the first time Jia is working within the tepid confines of a genre and he does remarkably well to leave his signature all over. But it is also true that Jia is one of the few directors who truly deserve a picture in this genre, given the consistency with which he has dealt with the theme of cultural transition in his films. Wang Hong Wei and Zhao Tao seem to be almost reprising their roles from Platform, which gives the film a touch of autobiographic authenticity, considering how often the director has used former actor as his alter ego. We are far from the sweet old days of Platform where the very sight of a train was rare. It’s now a matter of a few hours crossing the whole of China. As the professor and the students have their dinner, two actors in traditional theater costume perform at the restaurant with a huge bridge as the backdrop. Two characters travel on a boat in a river whose banks are adorned by old buildings, reminiscing and confessing how much they still love each other. They are, of course, going down the river of time with a clear knowledge that they can’t reverse its flow.

Picture Jia repenting for not being completely nostalgic in 24 City and deciding to assuage that guilt with a purely fictional feature. The 20-minute short Cry Me A River (2008) is just that. A group of middle class friends, well in their thirties, meet up, have dinner with one of their professors and talk in pairs about how their lives have been after they went their own ways. This must be the first time Jia is working within the tepid confines of a genre and he does remarkably well to leave his signature all over. But it is also true that Jia is one of the few directors who truly deserve a picture in this genre, given the consistency with which he has dealt with the theme of cultural transition in his films. Wang Hong Wei and Zhao Tao seem to be almost reprising their roles from Platform, which gives the film a touch of autobiographic authenticity, considering how often the director has used former actor as his alter ego. We are far from the sweet old days of Platform where the very sight of a train was rare. It’s now a matter of a few hours crossing the whole of China. As the professor and the students have their dinner, two actors in traditional theater costume perform at the restaurant with a huge bridge as the backdrop. Two characters travel on a boat in a river whose banks are adorned by old buildings, reminiscing and confessing how much they still love each other. They are, of course, going down the river of time with a clear knowledge that they can’t reverse its flow.

Hai Shang Chuan Qi (I Wish I Knew, 2010)

A project commissioned by the state in view of the upcoming Shanghai World Expo, Jia Zhang-ke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) is a thematic extension of 24 City and is much more freely structured and much broader in scope compared to its predecessor. The larger part of the film presents interviews with older residents of Shanghai (along with those of Taiwan and Hong Kong) who gleefully recollect their family’s history, which reveal the ever-growing chasm between the city’s past and present. Personal histories seem to be based on and shaped by the city’s tumultuous politics and culture. We see that the people being talked about were viewed as mere ideological symbols incapable of erring or transforming. In addition to his employment of mirrors and reflective surfaces suggesting both documentation and subjectivity, Jia films the interviewees in extremely shallow focus as if pointing out their being cut off from the present (It takes them the sound of breaking glass or the ring of a cellphone snap back to reality). This tendency is contrasted with the final few interviews of younger people where we witness how life can change course so quickly and how one can assume multiple social personalities on whim and float about like free entities. Losing one’s sense of existence in a particular environment is perhaps not a big price to pay after all for the seeming freedom of choice it gives. One’s history is no longer defined by one’s geographical location. One is no longer bound by dialectical ideologies. There is apparently no influence of the past on the present, in every sphere of life, whatsoever. Mistakes of the past are obscured by the glory of the present and the loss of values, by cries of progress. Jia’s view of the city is, against our wishes for a disapproving perspective, neither nostalgic nor rosy. It’s holistic.

A project commissioned by the state in view of the upcoming Shanghai World Expo, Jia Zhang-ke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) is a thematic extension of 24 City and is much more freely structured and much broader in scope compared to its predecessor. The larger part of the film presents interviews with older residents of Shanghai (along with those of Taiwan and Hong Kong) who gleefully recollect their family’s history, which reveal the ever-growing chasm between the city’s past and present. Personal histories seem to be based on and shaped by the city’s tumultuous politics and culture. We see that the people being talked about were viewed as mere ideological symbols incapable of erring or transforming. In addition to his employment of mirrors and reflective surfaces suggesting both documentation and subjectivity, Jia films the interviewees in extremely shallow focus as if pointing out their being cut off from the present (It takes them the sound of breaking glass or the ring of a cellphone snap back to reality). This tendency is contrasted with the final few interviews of younger people where we witness how life can change course so quickly and how one can assume multiple social personalities on whim and float about like free entities. Losing one’s sense of existence in a particular environment is perhaps not a big price to pay after all for the seeming freedom of choice it gives. One’s history is no longer defined by one’s geographical location. One is no longer bound by dialectical ideologies. There is apparently no influence of the past on the present, in every sphere of life, whatsoever. Mistakes of the past are obscured by the glory of the present and the loss of values, by cries of progress. Jia’s view of the city is, against our wishes for a disapproving perspective, neither nostalgic nor rosy. It’s holistic.

[“Black Breakfast” – Jia Zhang-Ke’s segment in Stories on Human Rights (2008)]