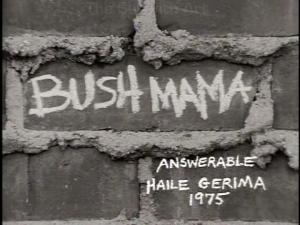

Bush Mama (1976)

Haile Gerima

English

“The wig is off my head.”

Ethiopian-born Haile Gerima, who was a part of the UCLA rebellion alongside the likes of Charles Burnett and Julie Dash, made Bush Mama (1976) as a part of his coursework at the university. The film follows a thirty-ish African-American woman named Dorothy (Barbara O. Jones) living with her daughter Luann (Susan Williams) and her new partner and Vietnam veteran T.C. (Johnny Weathers). Dorothy is unemployed, pregnant with T.C.’s child and lives on funds from a national welfare scheme intended for unemployed parents. T.C. is arrested one day on his way to a job interview and is imprisoned for a crime he apparently did not commit. Devastated, Dorothy vainly haunts the reception hall of the employment office. Meanwhile, the officials from the welfare department exhort Dorothy to abort her unborn in order to avoid giving her more funds. Decidedly, this is not what Hollywood, or any of the mainstream media, is willing to show us. For one, the protagonist is an African-American, a woman and a pauper, arguably the last combination the mainstream looks at. Then there is the plethora of volatile topics that the film alludes to or even confronts including Nixon, the Vietnam War, AFDC, Malcom X, the Watts riots and the legalization of abortion. Bush Mama’s function is to show that we sure might have seen all that in our mass media, but through the wrong words, wrong sounds and wrong images.

Ethiopian-born Haile Gerima, who was a part of the UCLA rebellion alongside the likes of Charles Burnett and Julie Dash, made Bush Mama (1976) as a part of his coursework at the university. The film follows a thirty-ish African-American woman named Dorothy (Barbara O. Jones) living with her daughter Luann (Susan Williams) and her new partner and Vietnam veteran T.C. (Johnny Weathers). Dorothy is unemployed, pregnant with T.C.’s child and lives on funds from a national welfare scheme intended for unemployed parents. T.C. is arrested one day on his way to a job interview and is imprisoned for a crime he apparently did not commit. Devastated, Dorothy vainly haunts the reception hall of the employment office. Meanwhile, the officials from the welfare department exhort Dorothy to abort her unborn in order to avoid giving her more funds. Decidedly, this is not what Hollywood, or any of the mainstream media, is willing to show us. For one, the protagonist is an African-American, a woman and a pauper, arguably the last combination the mainstream looks at. Then there is the plethora of volatile topics that the film alludes to or even confronts including Nixon, the Vietnam War, AFDC, Malcom X, the Watts riots and the legalization of abortion. Bush Mama’s function is to show that we sure might have seen all that in our mass media, but through the wrong words, wrong sounds and wrong images.

There is that very rare feeling of witnessing history being recorded as it is being made while watching Bush Mama. All the things it says and shows – all so detailed and so lived-in – seem so strongly hinged to the reality within which the film was made. You can sense how the welfare scheme was perceived by some sections as one of the causes of increase in crime rate, whereas Gerima’s film shows that the scheme was merely namesake and inconsequential (The echoes are felt even now when certain parties distort “from the rich to the poor” to “from those who earn to those who don’t”). Bush Mama clinically analyzes how the choices presented to this community of African-Americans (and also to other minorities, as Dorothy’s visit to the clinic indicates) are not really choices at all, exposing why the legalization of abortion and sterilization plans go hand-in-hand with the welfare scheme. Gerima adorns with film with all types of black people. People who believe that white folks have nothing to do with their problems and all the trouble is due to the blacks not behaving properly. There are those who think that it’s better to go on as it is. There are those who pretend that nothing’s wrong at all (There’s a sidesplitting vignette with a man whose experience limits his imagination). Then there are those, like T.C., who want to bring in a whole new order.

Bush Mama marries two distinct styles of filmmaking through its two narrative threads. The first section, which mostly follows Dorothy and her travail, is shot in text book cinema vérité format and is especially redolent of the early social films of Béla Tarr, which too deal with clear-cut issues like the national housing policy, unemployment and growing urban population. Like the Hungarian wunderkind, Gerima relies heavily on improvisation, draining the film of all theatricality and infusing each moment with utter spontaneity. He embraces ambient noise of the city and its streets, uses copious amount of handheld shots and effectively blurs the line between documentary and fiction (the ‘fiction’ here is only a thin veil over the truth anyway). If this first narrative thread hinges itself to melodramatic tradition, the second one flips it over, operating in a purely agitprop mode (a la early Makavejev and post-New Wave Godard) that attempts to drag back the film from the defeatism of the other segment towards activism. Characters talk to the camera, as if addressing the audience and provoking them to reassess and expand their sociopolitical view of the world. In a way, this dialectic between the two threads of the film – between passive acceptance and active resistance, between fatalism and existentialism – is the whole point of the film. Likewise, Dorothy herself stands somewhere between Joan of Arc and the militant African-American woman in the poster on her bedroom wall (During the final minutes, Gerima rhythmically cuts between the pregnant Dorothy, a masked Jesus Christ and the black man shot by the LAPD).

Gerima maintains a very dynamic aesthetic throughout in which the camera is rarely static, tracking, zooming and panning all the way (Burnett is credited as one of the DoPs). The director employs a range of camera angles and frame rates, cutting between them in a staccato fashion (also resembling Makavejev) that both reflects the protagonist’s kafkaesque view of events and provides a sense of immediacy to the proceedings. Gerima periodically cuts from reality to alternate reality, from objectivity to subjectivity, from the real to the surreal and from plot point to dead time. Shots of Dorothy wandering the bustling streets of the city (of which there are quite a few) are first shown in negative and only then are developed back to normal monochrome as if playfully flipping racial constructs and then drastically bringing the protagonist back to brutal reality. The production design accentuates the black and white colours of the mise en scène and the grainy 16mm stock provides a newsreel authenticity to the fiction that unfolds. But what is really striking about the visual design of the film is the director’s minimalist use of off-screen space in all the scenes. Be it scenes of comic relief, slice-of-life sequences in the African-American neighbourhood, dramatic episodes or sequences full of pathos, Gerima almost always fixates his camera on Dorothy’s face, capturing every gesture, contour and emotion on it. And through it, Gerima provides a comprehensive sketch of the African-American way of life.

Gerima maintains a very dynamic aesthetic throughout in which the camera is rarely static, tracking, zooming and panning all the way (Burnett is credited as one of the DoPs). The director employs a range of camera angles and frame rates, cutting between them in a staccato fashion (also resembling Makavejev) that both reflects the protagonist’s kafkaesque view of events and provides a sense of immediacy to the proceedings. Gerima periodically cuts from reality to alternate reality, from objectivity to subjectivity, from the real to the surreal and from plot point to dead time. Shots of Dorothy wandering the bustling streets of the city (of which there are quite a few) are first shown in negative and only then are developed back to normal monochrome as if playfully flipping racial constructs and then drastically bringing the protagonist back to brutal reality. The production design accentuates the black and white colours of the mise en scène and the grainy 16mm stock provides a newsreel authenticity to the fiction that unfolds. But what is really striking about the visual design of the film is the director’s minimalist use of off-screen space in all the scenes. Be it scenes of comic relief, slice-of-life sequences in the African-American neighbourhood, dramatic episodes or sequences full of pathos, Gerima almost always fixates his camera on Dorothy’s face, capturing every gesture, contour and emotion on it. And through it, Gerima provides a comprehensive sketch of the African-American way of life.

The film’s real forte lies in its sound design. Gerima uses a potpourri of sounds, noise and music for his soundtrack that goes well with the collage-like nature of the film’s visuals. Right from the first minute of the film, certain sounds and lines dominate the soundtrack. One of them is the voice of a woman reading out the terms and conditions of the welfare scheme and the seemingly endless number of questions to be answered to be eligible for it. “Do you understand? Do you agree?” they voices keep asking, as if the answer is going to make any difference at all. As the film proceeds, we share Dorothy’s frustration at these irritating sounds that seem to be floating everywhere in the air. In fact, these are indeed TV and radio waves. Bush Mama also touches upon the representation of African-American culture in popular media (the older women in the film seem to believe in the authority of television). The music, mostly jazz, that supplements this clutter of voices is rendered commendably by Onaje Kareem Kenyatta and the lyrics, too, serve either to supplement the narrative or to comment on the sociopolitical situation. Speaking of music, Bush Mama could be considered as the cinematic equivalent of a certain genre of hip-hop music as far as its basic aesthetic and cultural conventions are concerned. Actions and gestures that are improvised, the rhythmic editing, the recycled shots and the depiction of racial and economic discrimination could be mapped to their direct counterparts in rap and hip-hop.

The prime motif of the film is, quite clearly, that of the prison. One of Gerima’s targets in the film is the police’s seemingly baseless and systematic imprisonment of African-American men. In fact, the film’s most impressive sequence is shot in the jail T.C. is put in. The extended monologue begins with T.C. talking to the camera about the injustice towards black men by the city’s police. Shortly afterwards, the camera tracks over the adjacent prison cells where, too, black prisoners are held. One of the cells contains what looks like just the shadow of a man. It is only after a while that we see that it is in fact a person in flesh and blood standing deep inside the cell. It’s a bravura sequence, with a power and honesty seldom seen in propagandist cinema. Dorothy, on the other hand, is put in a whole different form of social prison. She has to act as the welfare officers say or she’ll go nowhere. They decide if she can have her baby or not. The police can put her in jail on whim and rape her daughter in her house. In parallel, Gerima imprisons Dorothy in visual (through his use of décor, the frustratingly chopped framing, restrictive mise en scène and suffocating close-ups) and aural (the white noise of the soundtrack that she can’t seem to get rid of) prisons. In all the cases, the characters seem to be in jail for a deed they did not commit or for a reason they do not understand.

Bush Mama fits well as a companion film to the most acclaimed work of the movement, Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977). While poetry oozed out from the edges of Burnett’s film, it is anger that emanates from the rough seams of Bush Mama. If that film was about conscious perseverance and the need to stick to one’s morality in the most troublesome times, this one is about doing away with such difficulties altogether. In other words, if Killer of Sheep was a romantic mini-spectacle about the indomitable nature of the human spirit, Bush Mama is the harsh behind-the-scenes making of that spectacle. Not that one is more inspiring or effective than the other. Dorothy speaking to T.C. at the end of Gerima’s film is as moving and affirmative as Stan waltzing with his wife in silence. Both are films that profess, albeit through radically different channels, that one can go on despite the adversities. However, unlike Killer of Sheep, Gerima’s film seriously questions if it could be done without a militant revolution and hence its agitprop mode of discourse. Consequently, the film ends with a call for revolution, explaining the need for “calculation” (perhaps a term which has found new meaning after 1968) and the necessity for the revolution to reach the grass roots. As Dorothy says: “I know you’re in jail, T.C., and angry. But most of the time I don’t understand your letters. Talk to me easy, T.C., coz I wanna understand.”

Bush Mama fits well as a companion film to the most acclaimed work of the movement, Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977). While poetry oozed out from the edges of Burnett’s film, it is anger that emanates from the rough seams of Bush Mama. If that film was about conscious perseverance and the need to stick to one’s morality in the most troublesome times, this one is about doing away with such difficulties altogether. In other words, if Killer of Sheep was a romantic mini-spectacle about the indomitable nature of the human spirit, Bush Mama is the harsh behind-the-scenes making of that spectacle. Not that one is more inspiring or effective than the other. Dorothy speaking to T.C. at the end of Gerima’s film is as moving and affirmative as Stan waltzing with his wife in silence. Both are films that profess, albeit through radically different channels, that one can go on despite the adversities. However, unlike Killer of Sheep, Gerima’s film seriously questions if it could be done without a militant revolution and hence its agitprop mode of discourse. Consequently, the film ends with a call for revolution, explaining the need for “calculation” (perhaps a term which has found new meaning after 1968) and the necessity for the revolution to reach the grass roots. As Dorothy says: “I know you’re in jail, T.C., and angry. But most of the time I don’t understand your letters. Talk to me easy, T.C., coz I wanna understand.”