It was the best of years, it was the worst of years. Best because a dizzying number of big and important projects surfaced this year and worst because I haven’t even been able to see even a fraction of that number, even though my film viewing hit an all-time high this December, That last bit was possible thanks to the city’s major international film festival, the first full-fledged fest that I’ve ever attended – a key event as far as my cinephilia is concerned. Although, I must admit, none of the new titles I saw at the fest blew me away, I was surprised by a handful of films that I think deserve wider exposure. (I’m thinking specifically of Jean-Jacques Jauffret’s debut film Heat Wave, a tragic, graceful hyperlionk movie in which piecing together the disorienting geography of Marseilles becomes as important as piecing together the four intersecting narratives.) Instead of continuing apologetically to emphasize my viewing gaps and to rationalize the countless number of entries on my to-see list, I present you another list, The Top 10 Films I Didn’t See This Year: (1) House of Tolerance (Bertrand Bonello, an indisputable masterpiece, probably) (2) Seeking the Monkey King (Ken Jacobs) (3) Margaret (Kenneth Lonergan) (4) This is Not a Film (Jafar Panahi/Mojtaba Mirtahmasb) (5) Century of Birthing (Lav Diaz) (6) Life Without Principle (Johnnie To) (7) The Loneliest Planet (Julia Loktev) (8) Hugo (Martin Scorsese) (9) Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Nuri Bilge Ceylan) (10) La Havre (Aki Kaurismaki). Now that that’s out of my system, here are my favorites from the ones I did get to see.

1. The Turin Horse (Béla Tarr/Ágnes Hranitzky, Hungary)

For a number of films this year, the end of the world became some sort of a theme park ride taken with ease, but none of them ventured as far as Béla Tarr’s mesmerizing, awe-inspiring farewell to cinema. With The Turin Horse, Tarr’s filmmaking traverses the whole gamut, moving away from the wordy realist pictures of his early phase to this extreme abstraction suggesting, in Godard’s phrasing, a farewell to language itself. Centering on a man, his daughter and their horse as they eke out a skeletal existence in some damned plain somewhere in Europe, The Turin Horse is the last chapter of a testament never written, an anti-Genesis narrative that finds God forsaking the world and leaving it to beings on earth to sort it all out by themselves. Tarr’s film is a remarkable cinematic achievement, primal in its physicality and elemental in its force. Nothing this year was so laden with doom and so brimming with hope at once as the ultimate image of the film, where father and daughter – now awakened, perhaps – sit in the darkness with nothing to confront but each other.

For a number of films this year, the end of the world became some sort of a theme park ride taken with ease, but none of them ventured as far as Béla Tarr’s mesmerizing, awe-inspiring farewell to cinema. With The Turin Horse, Tarr’s filmmaking traverses the whole gamut, moving away from the wordy realist pictures of his early phase to this extreme abstraction suggesting, in Godard’s phrasing, a farewell to language itself. Centering on a man, his daughter and their horse as they eke out a skeletal existence in some damned plain somewhere in Europe, The Turin Horse is the last chapter of a testament never written, an anti-Genesis narrative that finds God forsaking the world and leaving it to beings on earth to sort it all out by themselves. Tarr’s film is a remarkable cinematic achievement, primal in its physicality and elemental in its force. Nothing this year was so laden with doom and so brimming with hope at once as the ultimate image of the film, where father and daughter – now awakened, perhaps – sit in the darkness with nothing to confront but each other.

2. A Separation (Asghar Farhadi, Iran)

Asghar Farhadi’s super-modest yet supremely ambitious chronicle of class conflict in Tehran is a massive deconstruction project that strikes right at the heart of systems that define us. Accumulating detail upon detail and soaking the film in the ambiguity that characterizes the real world, A Separation reveals the utter failure of binary logic – which not only forms the foundation of institutions such as justice but also permeates and petrifies our imagination – in dealing with human dilemmas. Farhadi’s centrism is not a form of bourgeois neutrality that plagues many a war movies, it is a recognition that truth lies somewhere in the recesses between the contours of language, law and logic. Working with unquantifiable parameters such as irrationality and doubt, Farhadi’s film is something of an aporia in the discourses that surround cinema and reality and an urgent call for revaluation of approaches towards critical problems in general. Rigorously shot, edited and directed, A Separation is a genuinely empathetic yet highly intelligent slice of reality in all its messy complexity and breathtaking grace.

Asghar Farhadi’s super-modest yet supremely ambitious chronicle of class conflict in Tehran is a massive deconstruction project that strikes right at the heart of systems that define us. Accumulating detail upon detail and soaking the film in the ambiguity that characterizes the real world, A Separation reveals the utter failure of binary logic – which not only forms the foundation of institutions such as justice but also permeates and petrifies our imagination – in dealing with human dilemmas. Farhadi’s centrism is not a form of bourgeois neutrality that plagues many a war movies, it is a recognition that truth lies somewhere in the recesses between the contours of language, law and logic. Working with unquantifiable parameters such as irrationality and doubt, Farhadi’s film is something of an aporia in the discourses that surround cinema and reality and an urgent call for revaluation of approaches towards critical problems in general. Rigorously shot, edited and directed, A Separation is a genuinely empathetic yet highly intelligent slice of reality in all its messy complexity and breathtaking grace.

3. The Tree Of Life (Terrence Malick, USA)

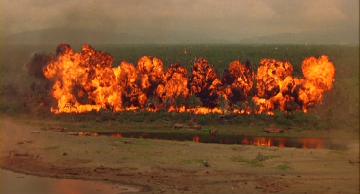

Juxtaposing the cosmic, the macroscopic and the infinite with the particular, the everyday and the finite, Terrence Malick’s fifth film The Tree of Life seeks to ask big questions. It is here that the director’s longstanding philosophical concerns find perfect articulation and efficacy in the specific form of the film. Seamlessly shifting between perspectives both all-knowing and limited, The Tree of Life posits the existence of a single shared consciousness across time and place, only a small part of which is each human being. It is also Malick’s most phenomenological film and mostly unfolds as a series of sensory impressions that both invites and resists interpretation. An awe-instilling tug-of-war between finitude and permanence, omniscience and ignorance, narrativization and immediate experience and rationalization and incomprehension, Malick’s unabashed celebration of the birth of consciousness – in general and in specific forms – locates the particular in the universal and vice versa. What lingers in the mind more than the grand ideas, though, are extremely minor details, which is pretty much what the medium must aspire to achieve.

Juxtaposing the cosmic, the macroscopic and the infinite with the particular, the everyday and the finite, Terrence Malick’s fifth film The Tree of Life seeks to ask big questions. It is here that the director’s longstanding philosophical concerns find perfect articulation and efficacy in the specific form of the film. Seamlessly shifting between perspectives both all-knowing and limited, The Tree of Life posits the existence of a single shared consciousness across time and place, only a small part of which is each human being. It is also Malick’s most phenomenological film and mostly unfolds as a series of sensory impressions that both invites and resists interpretation. An awe-instilling tug-of-war between finitude and permanence, omniscience and ignorance, narrativization and immediate experience and rationalization and incomprehension, Malick’s unabashed celebration of the birth of consciousness – in general and in specific forms – locates the particular in the universal and vice versa. What lingers in the mind more than the grand ideas, though, are extremely minor details, which is pretty much what the medium must aspire to achieve.

4. The Story Of Film: An Odyssey (Mark Cousins, UK)

A scandalous history, a disproportionate sense of importance and a frustrating accent. Critic-Filmmaker Mark Cousins’ project to present the story of cinema as a 15-part TV series appears doomed right from the conceptualization stage: can you even attempt to tell a story of film without omitting whole schools of filmmaking or national cinemas? Omit it certainly does, and unapologetically so, but when Cousins chronologically hops from one country to another, halting at particular films, scenes or even shots, providing commentary that is as insightful as they come and situating them in the larger scheme of things, you wouldn’t hesitate to lower your guard. Not only does Cousins’ 900-minute tribute to filmdom introduce us to names in world cinema rarely discussed about, but also presents newer approaches to canonical entries. Admirably inclusive (Matthew Barney and Baz Luhrmann find adjacent seats, so do Youssef Chahine and Steven Spielberg) and never condescending, The Story of Film exhibits towards the history of the form a sensitivity comparable to the finest of film criticism.

A scandalous history, a disproportionate sense of importance and a frustrating accent. Critic-Filmmaker Mark Cousins’ project to present the story of cinema as a 15-part TV series appears doomed right from the conceptualization stage: can you even attempt to tell a story of film without omitting whole schools of filmmaking or national cinemas? Omit it certainly does, and unapologetically so, but when Cousins chronologically hops from one country to another, halting at particular films, scenes or even shots, providing commentary that is as insightful as they come and situating them in the larger scheme of things, you wouldn’t hesitate to lower your guard. Not only does Cousins’ 900-minute tribute to filmdom introduce us to names in world cinema rarely discussed about, but also presents newer approaches to canonical entries. Admirably inclusive (Matthew Barney and Baz Luhrmann find adjacent seats, so do Youssef Chahine and Steven Spielberg) and never condescending, The Story of Film exhibits towards the history of the form a sensitivity comparable to the finest of film criticism.

What is stressed in Lynne Ramsay’s rattling third feature We Need to Talk About Kevin is not only the continuity between mother and son, but also the essential discontinuity. Where does the mother end and where does the son begin? Every inch of space between actors resonates with this dreadful ambiguity. The film is as much about Eva’s birth from the stifling womb of motherhood as it is Kevin’s apparent inability to be severed from her umbilical cord. Every visual in Ramsay’s chronicle of blood and birth works on three levels – literal, symbolic and associative – the last of which links the images of the film in subtle, subconscious and thoroughly unsettling ways. For the outcast Eva, the past bleeds into the present and every object, sound and gesture becomes a living, breathing reminder of whatever has been put behind. Ramsay’s intuitive, sensual approach to colour, composition and sound locates her directly in the tradition of the Surrealists and deems this unnerving, shattering, personal genre work as one of the most exciting pieces of cinema this year.

What is stressed in Lynne Ramsay’s rattling third feature We Need to Talk About Kevin is not only the continuity between mother and son, but also the essential discontinuity. Where does the mother end and where does the son begin? Every inch of space between actors resonates with this dreadful ambiguity. The film is as much about Eva’s birth from the stifling womb of motherhood as it is Kevin’s apparent inability to be severed from her umbilical cord. Every visual in Ramsay’s chronicle of blood and birth works on three levels – literal, symbolic and associative – the last of which links the images of the film in subtle, subconscious and thoroughly unsettling ways. For the outcast Eva, the past bleeds into the present and every object, sound and gesture becomes a living, breathing reminder of whatever has been put behind. Ramsay’s intuitive, sensual approach to colour, composition and sound locates her directly in the tradition of the Surrealists and deems this unnerving, shattering, personal genre work as one of the most exciting pieces of cinema this year.

An heir to the ideas of Dziga Vertov and Aleksandr Medvedkin, Kevin Macdonald’s Life in a Day is a moving, bewildering, charming, frustrating and dizzying snapshot of Planet Earth in all its glory, stupidity and complexity on a single day in 2011. An endless interplay of presence and absence, familiar and exotic, lack and excess, similarity and difference, the homogenous and the un-normalizable and the empowered and the marginalized, Life in a Day is a virtually inexhaustible film that is a strong testament to how many of us lived together on this particular planet on this particular day of this particular year. (That it represents only a cross section of the world population is a complaint that is subsumed by the film’s observations.) Each shot, loaded with so much cultural content, acts as a synecdoche, suggesting a dense social, political and historical network underneath. Most importantly, it taps right into the dread of death that accompanies cinematography: the heightened awareness of the finitude of existence and experience and the direct confrontation with the passing of time.

An heir to the ideas of Dziga Vertov and Aleksandr Medvedkin, Kevin Macdonald’s Life in a Day is a moving, bewildering, charming, frustrating and dizzying snapshot of Planet Earth in all its glory, stupidity and complexity on a single day in 2011. An endless interplay of presence and absence, familiar and exotic, lack and excess, similarity and difference, the homogenous and the un-normalizable and the empowered and the marginalized, Life in a Day is a virtually inexhaustible film that is a strong testament to how many of us lived together on this particular planet on this particular day of this particular year. (That it represents only a cross section of the world population is a complaint that is subsumed by the film’s observations.) Each shot, loaded with so much cultural content, acts as a synecdoche, suggesting a dense social, political and historical network underneath. Most importantly, it taps right into the dread of death that accompanies cinematography: the heightened awareness of the finitude of existence and experience and the direct confrontation with the passing of time.

7. Kill List (Ben Wheatley, UK)

On the surface, Ben Wheatley’s Kill List comes across like a sick B-movie with a mischievous sense of plotting, but on closer examination, it reveals itself as a serious work with clear-cut philosophical and political inclination. That its philosophy is inseparable from its mind-bending narrative structure makes it a very challenging beast. Kill List is the kind of kick in the gut that video games must strive to emulate if they aspire to become art. Indeed, Wheatley’s chameleon of a film borrows much from video games – from its division of a mission into stages announced by intertitles to the third-person-shooter aesthetic that it segues into – making us complicit with the protagonist and his moral attitude, later pulling the rug from our feet and leaving us afloat. Early in the film, Iraq war veteran and protagonist Jay mumbles that it was better if he was fighting the Nazis – at least, he would know who the enemy was. He learns the hard way that this ‘othering’ of the enemy into a mass of unidentifiable groups is a psychological strategy to protect and redeem himself, that it’s judgment that defeats us.

On the surface, Ben Wheatley’s Kill List comes across like a sick B-movie with a mischievous sense of plotting, but on closer examination, it reveals itself as a serious work with clear-cut philosophical and political inclination. That its philosophy is inseparable from its mind-bending narrative structure makes it a very challenging beast. Kill List is the kind of kick in the gut that video games must strive to emulate if they aspire to become art. Indeed, Wheatley’s chameleon of a film borrows much from video games – from its division of a mission into stages announced by intertitles to the third-person-shooter aesthetic that it segues into – making us complicit with the protagonist and his moral attitude, later pulling the rug from our feet and leaving us afloat. Early in the film, Iraq war veteran and protagonist Jay mumbles that it was better if he was fighting the Nazis – at least, he would know who the enemy was. He learns the hard way that this ‘othering’ of the enemy into a mass of unidentifiable groups is a psychological strategy to protect and redeem himself, that it’s judgment that defeats us.

8. Sleeping Beauty (Julia Leigh, Australia)

“Your vagina will be a temple” one elderly procurer assures Lucy, a twenty something university student who takes up odd jobs to pay her fees. Not only is the vagina a temple in Julia Leigh’s markedly assured debut feature, but the human body itself is a space that is to be furnished, maintained and rented out for public use. Leigh’s vehemently anti-realist examination of continuous privatization of the public and publicization of the private works against any kind of psychological or sociological realism, instead unfolding as an academic study of the human body as a site of control. Setting up a dialectic between pristine, clinical public spaces and messy, emotional private ones, Sleeping Beauty attempts to explore not our relationship to the spaces that we inhabit, but also to the space that we ourselves are. Consistently baffling and irreducible, Leigh’s film displays an eccentric yet surefooted approach to design, composition and framing, revealing the presence of a personality beneath. Sleeping Beauty is, for me, the most impressive debut film of the year.

“Your vagina will be a temple” one elderly procurer assures Lucy, a twenty something university student who takes up odd jobs to pay her fees. Not only is the vagina a temple in Julia Leigh’s markedly assured debut feature, but the human body itself is a space that is to be furnished, maintained and rented out for public use. Leigh’s vehemently anti-realist examination of continuous privatization of the public and publicization of the private works against any kind of psychological or sociological realism, instead unfolding as an academic study of the human body as a site of control. Setting up a dialectic between pristine, clinical public spaces and messy, emotional private ones, Sleeping Beauty attempts to explore not our relationship to the spaces that we inhabit, but also to the space that we ourselves are. Consistently baffling and irreducible, Leigh’s film displays an eccentric yet surefooted approach to design, composition and framing, revealing the presence of a personality beneath. Sleeping Beauty is, for me, the most impressive debut film of the year.

9. The Kid With A Bike (Jean-Pierre Dardenne/Luc Dardenne, Belgium/France)

The Dardenne brothers have turned out to be the preeminent documentarians of our world and their latest wonder The Kid with a Bike sits alongside their best works as an unadorned, incisive portrait of our time. Admittedly inspired by fairly tales, Dardennes’ film might appear like an archetypal illustration of innocence lured by the devil, but its parameters are all drawn from here and now. Structured as a series of transactions – persons, objects, moral grounds – where human interaction is inextricably bound to the movement of physical objects, the film presents our world as one defined by exchanges of all kind, but never reduces this observation to some cynical reading of life as a business. Also characteristic of Dardennes’ universe is the intense physicality that pervades each shot. Be it the boy scurrying about on foot or on bike or the countless number of doors that are opened and closed, the Dardennes, once more, show us that cinema must concern itself with superficies and it is on the surface of things that one can find depth.

The Dardenne brothers have turned out to be the preeminent documentarians of our world and their latest wonder The Kid with a Bike sits alongside their best works as an unadorned, incisive portrait of our time. Admittedly inspired by fairly tales, Dardennes’ film might appear like an archetypal illustration of innocence lured by the devil, but its parameters are all drawn from here and now. Structured as a series of transactions – persons, objects, moral grounds – where human interaction is inextricably bound to the movement of physical objects, the film presents our world as one defined by exchanges of all kind, but never reduces this observation to some cynical reading of life as a business. Also characteristic of Dardennes’ universe is the intense physicality that pervades each shot. Be it the boy scurrying about on foot or on bike or the countless number of doors that are opened and closed, the Dardennes, once more, show us that cinema must concern itself with superficies and it is on the surface of things that one can find depth.

10. The Monk (Dominik Moll, France/Spain)

Dominik Moll’s adaptation of Matthew Lewis’ eponymous novel concerning a self-righteous priest tempted by the devil could be described as an intervention of late nineteenth century tools – psychoanalysis and cinema – into a late eighteenth century text. Located on this side of the birth of psychoanalysis, Moll’s film comes across as essentially Freudian in the way it portrays the titular monk as a human being flawed by design and the church, society and family as institutions responsible for suppressing those basic impulses. Incest, rape and murder abound as hell breaks loose, but the film’s sympathy is clearly with the devil. The Monk uses an array of early silent cinema techniques including a schema that combines an impressionistic illustration of the protagonist’s sensory experience and expressionistic mise en scène to signal his irreversible descent into decadence. Alternating between metallic blues of the night and sun bathed brown, Moll’s film teeters on the obscure boundary between Good and Evil. Exquisitely composed and expertly realized, The Monk supplies that irresistible dose of classicism missing in the other films on this list.

Dominik Moll’s adaptation of Matthew Lewis’ eponymous novel concerning a self-righteous priest tempted by the devil could be described as an intervention of late nineteenth century tools – psychoanalysis and cinema – into a late eighteenth century text. Located on this side of the birth of psychoanalysis, Moll’s film comes across as essentially Freudian in the way it portrays the titular monk as a human being flawed by design and the church, society and family as institutions responsible for suppressing those basic impulses. Incest, rape and murder abound as hell breaks loose, but the film’s sympathy is clearly with the devil. The Monk uses an array of early silent cinema techniques including a schema that combines an impressionistic illustration of the protagonist’s sensory experience and expressionistic mise en scène to signal his irreversible descent into decadence. Alternating between metallic blues of the night and sun bathed brown, Moll’s film teeters on the obscure boundary between Good and Evil. Exquisitely composed and expertly realized, The Monk supplies that irresistible dose of classicism missing in the other films on this list.

Emir Kusturica’s Underground (1995) has been torn apart in certain sections as pro-Milosevic propaganda that brushes aside Serbia’s atrocities in the Balkan Wars. I think that’s not only being too harsh on a relatively benign satire but also that it ascribes way too much intention and focus to a film that’s riddled with ideological inconsistencies, like most films. True that it presents Yugoslavia under Tito as a Platonic cave whose residents mistake the shadows on the wall – sometimes literally, as when the inmates of an underground cell watch faked footage from WW2, which they think is still on – for truth and who are kept united under a phantom enemy while being blind to internal fault lines. But construing Kusturica’s generally sentimental lament about the breakup of a nation as brothers start killing brothers and friends turn on each other as a case for Serbia comes across as a pre-determined approach to the film which writes down the answers before the questions. What’s most inviting about Underground is how it keeps poking at the nexus between politics and cinema. Marko (Miki Manojlović), whose rise to power mirrors Tito’s, appears to us like a filmmaker figure, directing his historical actors in an underground set illuminated by high-key lighting and marked by a bizarre communal mise en scène. (And what of Tito himself, who could be the seen as the helmer of a chaotic crew made to act out a Communist metanarrative?) The deep hierarchy of performances that pervades the film aptly throws light on the loss of “reality” and the alienation from history that seems to have characterized Yugoslavia’s tumultuous half-century since the end of the Second World War.

Emir Kusturica’s Underground (1995) has been torn apart in certain sections as pro-Milosevic propaganda that brushes aside Serbia’s atrocities in the Balkan Wars. I think that’s not only being too harsh on a relatively benign satire but also that it ascribes way too much intention and focus to a film that’s riddled with ideological inconsistencies, like most films. True that it presents Yugoslavia under Tito as a Platonic cave whose residents mistake the shadows on the wall – sometimes literally, as when the inmates of an underground cell watch faked footage from WW2, which they think is still on – for truth and who are kept united under a phantom enemy while being blind to internal fault lines. But construing Kusturica’s generally sentimental lament about the breakup of a nation as brothers start killing brothers and friends turn on each other as a case for Serbia comes across as a pre-determined approach to the film which writes down the answers before the questions. What’s most inviting about Underground is how it keeps poking at the nexus between politics and cinema. Marko (Miki Manojlović), whose rise to power mirrors Tito’s, appears to us like a filmmaker figure, directing his historical actors in an underground set illuminated by high-key lighting and marked by a bizarre communal mise en scène. (And what of Tito himself, who could be the seen as the helmer of a chaotic crew made to act out a Communist metanarrative?) The deep hierarchy of performances that pervades the film aptly throws light on the loss of “reality” and the alienation from history that seems to have characterized Yugoslavia’s tumultuous half-century since the end of the Second World War.