As of today, my critical activity stretches over fifty-three years, with a gap between 1969 and 1982 that can be easily explained: Cahiers du cinema had suddenly converted to the cult of Marx. Oh, Karl was a nice guy with a bunch of good ideas, but I confess having trouble working in his sole dominion.

My first texts were pinched from Rivette and Truffaut: I devoured their prose on my way to high school on Wednesday mornings (the day the Arts weekly hit the stands) at the risk of getting run over. I learnt their writing by heart. This groupie mentality, coupled with an inferiority complex, didn’t sit well with me. That’s why I revolted. I frequently reproached Truffaut for some of his texts, something which irritated him. I don’t know if he understood the painful ambiguity of my status as a conformist. Today I regret having upbraided him at a time when not everything was going easy for him.

At the same time, I multiplied my oaths of loyalty to Truffaut. He had replaced the old guard and he thought that I and Straub were going to overtake him, just like Barbara Bates was to overtake Anne Baxter who replaced Bette Davis in Mankiewicz’s All About Eve. And when chatting with Straub at the entrance of a theatre, I had to hide whenever I saw Truffaut coming, who suspected me of colluding with Straub…

My other favourite critic was Georges Sadoul; I wanted to become the Sadoul of Hitchcocko-Hawsians, a daring paradox if we think that Truffaut was diametrically opposed to Sadoul… I admired the clarity of his writing, his encyclopaedic mind, his kindness, even if the content of his texts often seemed odious to me. His adherence to communism, for which he was criticized, particularly expressed his wish to belong to one family or the other (there was the Surrealist family before this). In fact, he used to snore at the CP meetings.

I too felt the need for a family. Things were a little turbulent during my adolescence. There were families that I chose myself later, that at Cahiers, the Société des réalisateurs de films, les Films d’ici etc. It was the same situation with the others, such as Godard, who came to Cahiers because it was for him an oasis of civilization, a point of reference, essential for the morale, in face of adversity or stupidity.

Why was I accepted so easily at Cahiers at the age of eighteen?

Because, the perfect bookworm that I was, I was the most well-informed cinephile in Paris.

And then it was always nice to have fans at a time when the straight-shooters of Cahiers were broke and, moreover, highly contested.

Everyone at Cahiers sensed my passion for cinema, which appeared worthy of respect.

And I was the Naïf, the innocent one, the “blue-eyed boy of Cahiers” in Rohmer’s words, the fan incapable of dirty tricks (frequent in the milieu). I was even surprised the day Lydie Doniol-Valcroze handed me my first cheque. I would’ve paid to be able to write in the “yellow magazine”.

Most of all, I made people laugh because I spoke, because I wrote. When I used to bring my papers to Rohmer, I looked forward to the moment he would blush, the moment when tears of laughter would trickle down his right cheek. If you knew Rohmer, you’d know it wasn’t easy to get to this point. For me, it was the kicker. Also, when Daney admitted to me later that the first text he rushed to whenever he opened Cahiers was mine.

I must confess that, on the 5th of November 1955, I almost fainted when I opened Truffaut’s letter where he told me that my article on Ulmer was accepted at Cahiers. At that second, my whole life was planned out, with several pitfalls to be avoided. The hardest part was done. Now that I had my foot on the stirrup, the passage to filmmaking was like dropping a letter at the post office: I’d written the first long and serious text on Godard, so Jean-Luc, that marvellous Pygmalion of French cinema, advised his producer (who was on his knees since the success of À bout de souffle) to produce my film.

In the beginning, my texts were a little too reverential towards Rivette and Truffaut. It was ridiculous to suck up to them: it was obvious that I took their side in all matters, no matter they wrote. There were also pointless gibes in my articles against overrated directors.

But soon I tried to be more poised and, especially, to be always comprehensible. The great fad at Cahiers then was to write unreadable texts. Demonsablon was a champion of this literature. There was a snobbism of hermeticism. If the reader didn’t understand a text printed on the fine, glazed paper of the magazine, it meant that the editor was superior to him. Even Bazin gave in at times to the sirens of obscurity.

My ingenuousness brought a breath of fresh air.

Godard pointed out to me that my strong point was the art of the catchphrase, the art of finding the right title, more than of getting lost in long sentences like Faulkner, my literary god at the time. And I tried to follow this advice.

My first texts were disorderly, strings of readymade sentences already read somewhere else, sweeping, gratuitous stylistic effects, pretty pirouettes and aggressive positions to get myself noticed (the very first articles by Truffaut, from the year 1953, and Godard were of the same kind), to the point that, in the beginning of 1957, Rohmer made me completely rewrite my text on Eisenstein. He explained to me that every sentence must have an internal coherence and that each one must be organically linked to the next. The ABCs, you’d think. But no professor told me that in the high school or the university. They were too square, always dedicated to teaching stupid rules (no “I”, introduction-thesis-antithesis-synthesis). In a word, it was Rohmer who taught me to write. And it was very kind of him to not have rejected my text outright.

Bazin, too, had blocked some of my writings at Cahiers or at the Éditions du Cerf. I’m grateful to him for that today for I would’ve found myself guilty of having produced many stupidities. Bazin considered me an irresponsible, mad, young dog of nineteen. That’s why I was so moved later when he complimented me for my review of Les Tricheurs.

I have thus chosen in this collection texts defended or praised by Rohmer (A Quiet American), by Godard (Men in War and the Tazieff) etc. Rivette told me later that my text on Les Honneurs de la guerre, the first Jean Dewever film, had made him like the film. I’d never have thought of receiving such a tribute from a man from whom I’d stolen so much.

My texts try to resume Truffaut’s principle: start from the particular (the picturesque if possible) – a detail from the film – to veer into the General. Never the opposite, as in the worst kind of criticism which stopped at the General (especially in the years 58-69).

The golden rule: every good film engenders a specific critical approach.

To make the reader laugh, to interest him, was my first concern. I’d set down the list of possible word plays before writing a text. To help inspire me, Rohmer had offered me a copy of the latest Vermot almanac.

I tried to be simple (didn’t always succeed), to narrate the story of a film in a few lines, which still remains an excellent exercise.

Before writing on an important film, I’d read the original novel end to end or skim through it – something which few did. Even Bazin, who was a serious guy, had produced five pages in Cahiers on The Red Badge of Courage without having read the book, which was as famous in the USA as Le Grand Meaulnes is in France.

I shouldn’t tell you this, but I always made sure I made a negative remark when I wrote a lot of good things about a film. I also practiced the opposite. It gives the reader the (misleading) impression that the critic is objective.

Similarly, I’d gather technical information – number and duration of shots and shooting, budget, box office of the film etc. – which made subjective positions sound objective.

I’d manage to insert a shock sentence which could help advertise the film, thereby glorifying the film and myself. My greatest shortcoming when it came to a good film by a great director was to attribute everything that was good to my cherished auteur and everything that was bad to his collaborators. The truth is not so simple.

My first years as a critic (1959-1960) were the ones that brought me the most attention from readers, perhaps because people were then interested in criticism that was less tepid, less ecumenical and laudatory than today, perhaps also because I wrote in a flagship magazine which had all the good articles.

Texts today are more dispersed, and they get lost.

Nevertheless, my writings from that time are less pertinent than the ones I’ve written in the past few years, which are more level-headed, generally without controversy and very precise owing to my practical knowledge of filmmaking and, thanks to time, my deeper knowledge of the history of cinema: I must’ve seen eight thousand films in sixty-five years.

This manifestly positive evolution of the quality of my writing is at loggerheads with my career as a filmmaker. I don’t think my later films are any more successful than the earlier ones. My most appreciated productions belong to the midperiod of my career (from 1977, year of Genèse d’un repas, to Essai d’ouverture in 1988).

Here I want to note the similarity between criticism and documentary filmmaking: in both, one studies something which already exists, a projected film or a city, a place or a social fact.

The difference, at least for me: to be a film critic is to say good things about a film; to be a filmmaker is to say bad things about the society, about the absurdity of the world, about a city, about everything… the filmmaker criticizes, and the critic praises.

Today, as a critic, I have the advantage over other reviewers of not being dependent on current events. From 1957 to 1960, I lived on commissions as a critic and so I was subjected to weekly releases by my editors-in-chief. In 2009, I’m a freelancer and can allow myself to write on unknown filmmakers from the present or the past.

These are the days of video criticism. There’s not much difference in there for me who, in 1960, was practically doing video criticism before it even existed, with my chronometer and the light pen that Sadoul had found for me in Moscow and I used to see films twice consecutively in the theatre. But, with video, it’s nevertheless easier and it avoids silly mistakes. The essential thing, today as yesterday, is not to flit from one thing to another, but study one or two points of the film more attentively. I’ve written seven pages on James Stewart’s acting during one and a half minutes of film.

Almost all these texts were written very quickly.

This speed (which I find again during the drafting of the scripts of my films: two mornings for a short film, three to twenty-four days for a feature film) gives me the pleasure of observing the faces of my astonished sponsors when I hand them over my copy. One of them asked me for twelve pages on Bergman. It was complete three hours later, and Rivette even found it good.

This promptness is also a (completely relative) form of humility. You shouldn’t think that the Culture revolves around you.

It’s a question of personal discipline, of habit. You must be able to take the plunge, to abandon yourself. To me, it’s a question of honesty before the reader. I give him what I feel without calculation or detour.

You are deemed guiltier when you commit a crime with premeditation.

It should be the same for an article (or a script).

I think this practice stems from an opposition to my father. He used to write several letters (to Mitterrand, to Hitler and tutti quanti) which he’d start all over when he made a mistake. It’d take him all day, a little like the hero of El. And I love doing the opposite. Many of my acts were accomplished against the father (even though, the diplomat that I am, I wasn’t on bad terms with him). My first girlfriend was Jewish while he was very anti-Semitic. And I specialized in eulogizing Jewish filmmakers (Lang, Preminger, Lubitsch, Ulmer, Gance, Truffaut, Fuller, DeMille). I made a corpse of my dad in my Billy the Kid.

I say I’m fast, but I’m boasting. My texts with writing quotations (on DeMille, Deleuze or Ellroy) took a lot of time. Moreover, what I write is the result of sixty years of cinematic experiments.

Whenever it’s possible, I let these texts sleep in a drawer. I let them simmer for thirteen days in order to look at them with new eyes.

It could be longer. The first version of my text on Bresson is fifteen years old. Re-reading after a long time, you correct everything very fast and with much fairness.

My articles sometimes contain a dense analysis, far too dense. They must always be aerated by humour. They fail otherwise.

What use writing on Renoir or Rossellini?

Besides, Truffaut would never have allowed me to do it: it was his private hunting ground. So, I prefer being THE FIRST. The first to extol a great filmmaker forgotten or unknown at the time: Baldi, Bava, Bernard-Deschamps, Compton, Cottafavi, Dewever, Ferroukhi, Fuller, Godard, Guiraudie, Hers, Itami, Jansco, Kumashiro, Oshima, Rudolph, Skolimowski, Ulmer, Valentin, Zurlini.

I’ve corrected certain articles (very little). For example, when I made a remark based on an wrong colour grading, or when I invoked an event from the era unknown to today’s reader, or when a piece of information turned out to be false, or when my editor in chief had changed the title, made typographical mistakes or didn’t notice that a line was skipped.

[From Luc Moullet’s Piges choisies (2009, Capricci). See Table of Contents]

At a time when Daesh funds itself by trafficking cultural artifacts and Europe announces asylum for threatened art works, Sokurov’s marvelous, piercing film offers nothing less than a revisionist historiography of art itself. For Francofonia, History is not the content of art but its very skin. Museums flatten time, and justifiably present their contents as the highest achievements of a culture, obfuscating, in effect, their history as objects involved in power brokerage, class conflict and market manipulation. Sokurov’s film flips this perspective inside out, identifying art as being frequently the currency of diplomatic power possessing the capacity to purchase peace and as being instruments in service of totalitarian collaboration. Napoleon,

At a time when Daesh funds itself by trafficking cultural artifacts and Europe announces asylum for threatened art works, Sokurov’s marvelous, piercing film offers nothing less than a revisionist historiography of art itself. For Francofonia, History is not the content of art but its very skin. Museums flatten time, and justifiably present their contents as the highest achievements of a culture, obfuscating, in effect, their history as objects involved in power brokerage, class conflict and market manipulation. Sokurov’s film flips this perspective inside out, identifying art as being frequently the currency of diplomatic power possessing the capacity to purchase peace and as being instruments in service of totalitarian collaboration. Napoleon,  The jeu de mots in the title says it all. Not only is this deeply death-marked, Ozuvian film an unordinary home movie, but it is also a film about not having a home. Composed of footage shot in the filmmaker’s mother’s Brussels apartment and recorded video-conference sessions between the two, No Home Movie contrasts Akerman’s professional nomadism with the perennial confinedness of her mother Natalia. Between Chantal’s constant off-screen presence and Natalia’s self-imposed captivity (within the apartment as well as the computer screen), between Here and Elsewhere, lies the film’s true space – a part-real, part-virtual space of filial anxiety and affection. Akerman’s matrilineal counterpart to Porumboiu’s

The jeu de mots in the title says it all. Not only is this deeply death-marked, Ozuvian film an unordinary home movie, but it is also a film about not having a home. Composed of footage shot in the filmmaker’s mother’s Brussels apartment and recorded video-conference sessions between the two, No Home Movie contrasts Akerman’s professional nomadism with the perennial confinedness of her mother Natalia. Between Chantal’s constant off-screen presence and Natalia’s self-imposed captivity (within the apartment as well as the computer screen), between Here and Elsewhere, lies the film’s true space – a part-real, part-virtual space of filial anxiety and affection. Akerman’s matrilineal counterpart to Porumboiu’s  Taxi opens with a shot of downtown Tehran photographed from the dashboard of a car. Announcing Panahi’s first cinematic outdoor excursion since his house arrest in 2011, this shot sets up the dialectics that would define the film: home/world, individual/social and freedom/captivity. Through the course of Taxi, the spied-upon filmmaker drives around the city in the guise of a cabbie, chauffeuring clients-actors from various strata of the society, and realizing a pre-scripted scenario with them whose urgent, didactic purpose can’t be more obvious. The Iranian state has forged a private prison for Panahi from the public spaces of Tehran, allowing him a mobility and false freedom that’s regulated by its watchful eyes. Panahi turns this power dynamic upside down, transforming the private space of the vehicle into a public space for debate, discussion, instruction and critique. Watching the film, I was constantly reminded of that saying beloved of Wittgenstein: “It takes all kinds to make a world”. Panahi’s very presence in the film – his image, his voice – becomes an audacious act of political defiance, a gesture of tremendous existential courage that stares at the possibility of death floating in the air. Taxi makes cinema still matter.

Taxi opens with a shot of downtown Tehran photographed from the dashboard of a car. Announcing Panahi’s first cinematic outdoor excursion since his house arrest in 2011, this shot sets up the dialectics that would define the film: home/world, individual/social and freedom/captivity. Through the course of Taxi, the spied-upon filmmaker drives around the city in the guise of a cabbie, chauffeuring clients-actors from various strata of the society, and realizing a pre-scripted scenario with them whose urgent, didactic purpose can’t be more obvious. The Iranian state has forged a private prison for Panahi from the public spaces of Tehran, allowing him a mobility and false freedom that’s regulated by its watchful eyes. Panahi turns this power dynamic upside down, transforming the private space of the vehicle into a public space for debate, discussion, instruction and critique. Watching the film, I was constantly reminded of that saying beloved of Wittgenstein: “It takes all kinds to make a world”. Panahi’s very presence in the film – his image, his voice – becomes an audacious act of political defiance, a gesture of tremendous existential courage that stares at the possibility of death floating in the air. Taxi makes cinema still matter. A beautiful marine cousin to Guzman’s previous film, Nostalgia for the Light (2010), The Pearl Button turns its attention from the arid stretches of the Atacama to the waterfront and ice field of Southern Patagonia. Threading metaphor over metaphor, the director fashions a typically associative, richly suggestive essay film that turns the nature documentary form on its head. Guzman’s film plumbs the depths of the ocean, trying to uncover traces of suppressed, unseen history embodied by countless “missing people” – a project that derives its impetus from the filmmaker’s bittersweet childhood experience of the sea. Despite Chile’s economic indifference to its 4000-kilometer-long coastline, he notes, the sea has been indispensable those in power, serving first as the entry point of the European invaders, who wiped out the Patagonian natives, and then as the dumping ground of political prisoners during the Pinochet regime. Guzman teases out the different values that the sea holds for him, the autochthons and the Chilean state, in effect politicizing and historicizing that which conventional wisdom takes to be apolitical and ahistorical: geography and the perception of it. The result is a film of immense poetry and horror – a horror that only poetry can convey.

A beautiful marine cousin to Guzman’s previous film, Nostalgia for the Light (2010), The Pearl Button turns its attention from the arid stretches of the Atacama to the waterfront and ice field of Southern Patagonia. Threading metaphor over metaphor, the director fashions a typically associative, richly suggestive essay film that turns the nature documentary form on its head. Guzman’s film plumbs the depths of the ocean, trying to uncover traces of suppressed, unseen history embodied by countless “missing people” – a project that derives its impetus from the filmmaker’s bittersweet childhood experience of the sea. Despite Chile’s economic indifference to its 4000-kilometer-long coastline, he notes, the sea has been indispensable those in power, serving first as the entry point of the European invaders, who wiped out the Patagonian natives, and then as the dumping ground of political prisoners during the Pinochet regime. Guzman teases out the different values that the sea holds for him, the autochthons and the Chilean state, in effect politicizing and historicizing that which conventional wisdom takes to be apolitical and ahistorical: geography and the perception of it. The result is a film of immense poetry and horror – a horror that only poetry can convey. The most impressive debut film of the year, Alexandra Gerbaulet’s ambitious, intoxicating Shift excavates the evolution of her hometown, Salzgitter, along with that of her family with archaeological care and scientific detachment. In Gerbaulet’s heady narration, anchored by a powerful, quasi-declamatory, rhythmic voiceover, Salzgitter’s transformation from a Nazi mining stronghold and concentration camp, through a waning industrial hub and to a nuclear waste dump parallels the gradual disintegration of the Gerbaulet family under the weight of unemployment, sickness and sexual repression. The filmmaker closely intercuts photographs and diary entries of her mother with impersonal material from popular and scientific culture, weaving in and out of both registers with ease. Gerbaulet’s film is literally an unearthing project, as the director scoops out the various historical, political and geographical layers of this war-weathered city whose tranquil current-day model housing sits atop a makeshift Jewish graveyard consisting of camp workers buried using industrial debris. “Man gets used to everything, even the scar”, declares the narrator bluntly. Shift unscrambles such a habituated view of things, observing the tragicomic tautologies in which history revisits the city. The more you dig, it would seem, the more of the same you get.

The most impressive debut film of the year, Alexandra Gerbaulet’s ambitious, intoxicating Shift excavates the evolution of her hometown, Salzgitter, along with that of her family with archaeological care and scientific detachment. In Gerbaulet’s heady narration, anchored by a powerful, quasi-declamatory, rhythmic voiceover, Salzgitter’s transformation from a Nazi mining stronghold and concentration camp, through a waning industrial hub and to a nuclear waste dump parallels the gradual disintegration of the Gerbaulet family under the weight of unemployment, sickness and sexual repression. The filmmaker closely intercuts photographs and diary entries of her mother with impersonal material from popular and scientific culture, weaving in and out of both registers with ease. Gerbaulet’s film is literally an unearthing project, as the director scoops out the various historical, political and geographical layers of this war-weathered city whose tranquil current-day model housing sits atop a makeshift Jewish graveyard consisting of camp workers buried using industrial debris. “Man gets used to everything, even the scar”, declares the narrator bluntly. Shift unscrambles such a habituated view of things, observing the tragicomic tautologies in which history revisits the city. The more you dig, it would seem, the more of the same you get. One of my favorite films of the year is a commercial for a major power corporation made by a 106-year-old artist.

One of my favorite films of the year is a commercial for a major power corporation made by a 106-year-old artist.  Thomas McCarthy’s dramatization of Boston Globe’s exposé of child abuse in the Church is a robust, smart procedural that is less about picking apart the Catholic establishment than about elucidating the epistemological processes of the Information Age. Set at the transitional period between print and online news media, the film underscores the soon-to-be-outmoded physical nature of journalistic investigation. There are no antagonists of the traditional kind in Spotlight. The only obstacles to the knowledge required to carry out the exposé are the numerous procedures and institutional protocols that have for objective the protection or publication of information. It is telling that the entire film is about a pack of newswriters seeking information that’s already out in the open. What’s more, the film recognizes that the Spotlight team’s attempts to mount an institutional critique is itself inscribed within kindred ideological biases, operational strategies and structural iniquities of Boston Globe as an institution and that the metaphysical crisis that their story can potentially wreak amidst readers is but similar to the disillusionment the newsmen experience vis-à-vis their Protestant weltanschauung. With relatively uncommon formal and ethical restraint, McCarthy crafts an arresting film about how a society’s narratives are made, predicated they are as much on the dissemination of information as on their marginalization.

Thomas McCarthy’s dramatization of Boston Globe’s exposé of child abuse in the Church is a robust, smart procedural that is less about picking apart the Catholic establishment than about elucidating the epistemological processes of the Information Age. Set at the transitional period between print and online news media, the film underscores the soon-to-be-outmoded physical nature of journalistic investigation. There are no antagonists of the traditional kind in Spotlight. The only obstacles to the knowledge required to carry out the exposé are the numerous procedures and institutional protocols that have for objective the protection or publication of information. It is telling that the entire film is about a pack of newswriters seeking information that’s already out in the open. What’s more, the film recognizes that the Spotlight team’s attempts to mount an institutional critique is itself inscribed within kindred ideological biases, operational strategies and structural iniquities of Boston Globe as an institution and that the metaphysical crisis that their story can potentially wreak amidst readers is but similar to the disillusionment the newsmen experience vis-à-vis their Protestant weltanschauung. With relatively uncommon formal and ethical restraint, McCarthy crafts an arresting film about how a society’s narratives are made, predicated they are as much on the dissemination of information as on their marginalization. ergei Loznitsa’s formidable follow-up to Maidan (2014) furthers the earlier film’s exploration of the aesthetics and mechanics of revolution, capturing a people coming together to make sense of a political limbo. Without context or a framing perspective, the film drops us straight into the streets of St. Petersburg just after the attempted reactionary coup d’état in Moscow in 1991. Confusion and mundanity – not heroics and determination – reign as we observe the formative process of a people’s movement and the imagined/imaginary social glue that causes individuals to cohere into a group. State apparatuses compete with each other for imposing a narrative onto the events, while the very toponymy of the city becomes an ideological battleground. Working off priceless archival footage, much of which is incredibly reminiscent of the filmmaker’s own cinematographic style, Loznitsa provides an invaluable glimpse into the unfurling of history, chronicling how numerous banal, unsure gestures and actions snowball into Historical Events. If Eisenstein’s better-than-the-original recreation of the October Revolution was the abstraction of materialist history into ideas, Loznitsa’s film, taking place at the same Palace Square 63 years later, rescues history from the reductions of ideology and brings it right back into the realm of the material.

ergei Loznitsa’s formidable follow-up to Maidan (2014) furthers the earlier film’s exploration of the aesthetics and mechanics of revolution, capturing a people coming together to make sense of a political limbo. Without context or a framing perspective, the film drops us straight into the streets of St. Petersburg just after the attempted reactionary coup d’état in Moscow in 1991. Confusion and mundanity – not heroics and determination – reign as we observe the formative process of a people’s movement and the imagined/imaginary social glue that causes individuals to cohere into a group. State apparatuses compete with each other for imposing a narrative onto the events, while the very toponymy of the city becomes an ideological battleground. Working off priceless archival footage, much of which is incredibly reminiscent of the filmmaker’s own cinematographic style, Loznitsa provides an invaluable glimpse into the unfurling of history, chronicling how numerous banal, unsure gestures and actions snowball into Historical Events. If Eisenstein’s better-than-the-original recreation of the October Revolution was the abstraction of materialist history into ideas, Loznitsa’s film, taking place at the same Palace Square 63 years later, rescues history from the reductions of ideology and brings it right back into the realm of the material. A remarkable American counterpart to J. P. Sniadecki’s The Iron Ministry (2014), In Transit unfolds predominantly as a series of interviews with a mixed bag of travellers on board The Empire Builder, a long-distance passenger train running over 3500 kilometers and spanning almost the entire width of the United States. The accounts of passengers seeking out professional and financial breakthroughs evoke the pioneer myth hinged on a “Go West” imperative while the stories of those aboard in search of their ‘calling’ demonstrate the essentially spiritual, even religious nature of their pilgrimage-like journey. The diversity and range of the interviewees and their interactions help the film depict the train as a miniature America, à la Stagecoach, and carve out a quasi-utopian space in which members across class, race and gender divides get an opportunity to converse with each other without personal baggage. Nonetheless, In Transit is less a cultural vision of a possible America than an existential meditation on what makes people embark on these journeys. One elderly war veteran remarks that he’ll never be able to see these plains again. To cite John Berger, “the desire to have seen has a deep ontological basis.”

A remarkable American counterpart to J. P. Sniadecki’s The Iron Ministry (2014), In Transit unfolds predominantly as a series of interviews with a mixed bag of travellers on board The Empire Builder, a long-distance passenger train running over 3500 kilometers and spanning almost the entire width of the United States. The accounts of passengers seeking out professional and financial breakthroughs evoke the pioneer myth hinged on a “Go West” imperative while the stories of those aboard in search of their ‘calling’ demonstrate the essentially spiritual, even religious nature of their pilgrimage-like journey. The diversity and range of the interviewees and their interactions help the film depict the train as a miniature America, à la Stagecoach, and carve out a quasi-utopian space in which members across class, race and gender divides get an opportunity to converse with each other without personal baggage. Nonetheless, In Transit is less a cultural vision of a possible America than an existential meditation on what makes people embark on these journeys. One elderly war veteran remarks that he’ll never be able to see these plains again. To cite John Berger, “the desire to have seen has a deep ontological basis.” One of a piece with Gianvito’s Vapor Trail (Clark) (2010), Wake continues its precedent’s important investigation into the ecological consequences of the presence of America’s largest military bases in the Philippines during most of the 20th century. Like Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind (2007), Wake is guided by the spirit of Howard Zinn’s approach to history and sketches an economically-founded account of US-Philippines political and cultural relations – a history that seems to be have been lamentably wiped off from the Filipino national consciousness. Gianvito juxtaposes images from the Philippine-American war with current day images from the contaminated Subic naval base area, suggesting, in effect, the poisonous persistence of an agonizing, unacknowledged history. Wake is imperfect cinema – unwieldy and resourceful – and employs fly-on-the-wall records, talking heads, on-screen text, photographs and news clips to mount a potent critique of a historiography defined political amnesia and economic opportunism. More importantly, it is a necessary reminder that imperialism is not always about presence, action and exercise of power but sometimes also about the refusal of these very elements, that history is not only a matter of events but also processes and phenomena and that geography is always political.

One of a piece with Gianvito’s Vapor Trail (Clark) (2010), Wake continues its precedent’s important investigation into the ecological consequences of the presence of America’s largest military bases in the Philippines during most of the 20th century. Like Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind (2007), Wake is guided by the spirit of Howard Zinn’s approach to history and sketches an economically-founded account of US-Philippines political and cultural relations – a history that seems to be have been lamentably wiped off from the Filipino national consciousness. Gianvito juxtaposes images from the Philippine-American war with current day images from the contaminated Subic naval base area, suggesting, in effect, the poisonous persistence of an agonizing, unacknowledged history. Wake is imperfect cinema – unwieldy and resourceful – and employs fly-on-the-wall records, talking heads, on-screen text, photographs and news clips to mount a potent critique of a historiography defined political amnesia and economic opportunism. More importantly, it is a necessary reminder that imperialism is not always about presence, action and exercise of power but sometimes also about the refusal of these very elements, that history is not only a matter of events but also processes and phenomena and that geography is always political.

Chan’s diaristic digital work is divided into chapters named after family members and unfurls as a process of piecing together of familial history. Through various confrontational interviews with her mother and father, the filmmaker attempts to understand their failed marriage, her strained relation with her step-father and the violence that has structured them both. Chan’s decision to put her entire life-story on film is a brave gesture, but the film closes upon itself, satisfied to be a melodrama valorizing personal experience over broader frameworks. (Consider, in contrast, the rigorous domestic formalism of Liu Jiayin or the socio-political tapestry of Jia Zhangke’s early work.) Chan misses the forest for the lone tree. Winner of the Adolfas Mekas award of the fest.

Chan’s diaristic digital work is divided into chapters named after family members and unfurls as a process of piecing together of familial history. Through various confrontational interviews with her mother and father, the filmmaker attempts to understand their failed marriage, her strained relation with her step-father and the violence that has structured them both. Chan’s decision to put her entire life-story on film is a brave gesture, but the film closes upon itself, satisfied to be a melodrama valorizing personal experience over broader frameworks. (Consider, in contrast, the rigorous domestic formalism of Liu Jiayin or the socio-political tapestry of Jia Zhangke’s early work.) Chan misses the forest for the lone tree. Winner of the Adolfas Mekas award of the fest. Beep assembles anti-communist propaganda material from the 60s and the 70s commissioned by the South Korean state that was based on the mythologizing of a young boy, Lee Seung-bok, slain by North Korean soldiers. With the unseen, absent boy-hero at its focus, Kim’s film depicts the dialectical manner in which a nation defines itself in relationship to an imagined Other. Kim makes minimal aesthetic intervention into the source material – our relation to it automatically ironic by dint of our very distance from the period it was made in – restricting himself to adding periodic beep sounds to the footage, producing something like a cautionary transmission from another world.

Beep assembles anti-communist propaganda material from the 60s and the 70s commissioned by the South Korean state that was based on the mythologizing of a young boy, Lee Seung-bok, slain by North Korean soldiers. With the unseen, absent boy-hero at its focus, Kim’s film depicts the dialectical manner in which a nation defines itself in relationship to an imagined Other. Kim makes minimal aesthetic intervention into the source material – our relation to it automatically ironic by dint of our very distance from the period it was made in – restricting himself to adding periodic beep sounds to the footage, producing something like a cautionary transmission from another world. Black Sun opens with a composition in deep space presenting a metonym for a country in the process of development: high-rise buildings in the background as a pair of actors in period costumes rehearse a scene in the foreground. In a series of Jia Zhangke-like vignettes of Saigon set in middle-class youth hangouts scored to pop songs and television sounds, interspersed with images of a metamorphosing city, we see the distance that separates art from reality and the middle-class from the changes around it. The film culminates in a complex, home-made long take following the protagonist across her house and out into the terrace, where she dances, presumably to the eponymous song.

Black Sun opens with a composition in deep space presenting a metonym for a country in the process of development: high-rise buildings in the background as a pair of actors in period costumes rehearse a scene in the foreground. In a series of Jia Zhangke-like vignettes of Saigon set in middle-class youth hangouts scored to pop songs and television sounds, interspersed with images of a metamorphosing city, we see the distance that separates art from reality and the middle-class from the changes around it. The film culminates in a complex, home-made long take following the protagonist across her house and out into the terrace, where she dances, presumably to the eponymous song. The most challenging and elusive film of the competition I saw is also the most hypnotic. Cloud Shadow gives us a narrative of sorts in first person about a group of people who go into the woods and dissolve in its elements. The film is obliquely a story of the fascination with cinema, of the trans-individualist communal experience it promises, of the desire to dissolve the limits of one’s body into the images and sounds it offers. With an imagery consisting of sumptuous tints, and nuanced colour gradation and superimpositions, the film enraptures as much as it evades easy intellectual grasp. The one film of the festival that felt most like a half-remembered dream.

The most challenging and elusive film of the competition I saw is also the most hypnotic. Cloud Shadow gives us a narrative of sorts in first person about a group of people who go into the woods and dissolve in its elements. The film is obliquely a story of the fascination with cinema, of the trans-individualist communal experience it promises, of the desire to dissolve the limits of one’s body into the images and sounds it offers. With an imagery consisting of sumptuous tints, and nuanced colour gradation and superimpositions, the film enraptures as much as it evades easy intellectual grasp. The one film of the festival that felt most like a half-remembered dream. Ferri’s teasing, playful Dog, Dear appropriates the filmed record of a Soviet zoological experiment in the 1940s in which scientists impart motor functions to different parts of a dead dog. In the incantatory soundtrack, a woman – presumably the animal’s owner – repeatedly conveys messages to it, with each of them prefaced by the titular term of endearment. Ferri’s film would serve sufficiently as a blunt political allegory about the dysfunction of communism, but I think it’s probably fashioning itself as a metaphysical question: the dog might well be kicking but is he alive? His physical resurrection will not be accompanied by a restoration of consciousness. He will not respond to his master’s voice.

Ferri’s teasing, playful Dog, Dear appropriates the filmed record of a Soviet zoological experiment in the 1940s in which scientists impart motor functions to different parts of a dead dog. In the incantatory soundtrack, a woman – presumably the animal’s owner – repeatedly conveys messages to it, with each of them prefaced by the titular term of endearment. Ferri’s film would serve sufficiently as a blunt political allegory about the dysfunction of communism, but I think it’s probably fashioning itself as a metaphysical question: the dog might well be kicking but is he alive? His physical resurrection will not be accompanied by a restoration of consciousness. He will not respond to his master’s voice. Put together from footage apparently shot over twenty years at a Thai army officer’s residence, Tesprateep’s film shows us four conscripts working in the general’s garden. We witness their camaraderie, their obvious boredom, the empty bravado in entrapping small animals and intimidating each other. The misuse of power by the officer in employing these youth to mow his lawn reflects a broader militaristic hierarchy, as is attested by the youths’ casual violence towards the animals and their brutal torturing of a prisoner. Endless, Nameless recalls Claire Denis in its emphasis on military performativity and Werner Herzog in its juxtaposition of idyllic nature and seething violence, all the while retaining an

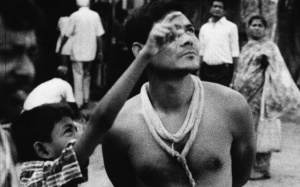

Put together from footage apparently shot over twenty years at a Thai army officer’s residence, Tesprateep’s film shows us four conscripts working in the general’s garden. We witness their camaraderie, their obvious boredom, the empty bravado in entrapping small animals and intimidating each other. The misuse of power by the officer in employing these youth to mow his lawn reflects a broader militaristic hierarchy, as is attested by the youths’ casual violence towards the animals and their brutal torturing of a prisoner. Endless, Nameless recalls Claire Denis in its emphasis on military performativity and Werner Herzog in its juxtaposition of idyllic nature and seething violence, all the while retaining an  In Fictitious Force, Widmann incidentally poses himself the age-old challenge of ethnological cinema; how to film the Other without imposing your own worldview on him? The filmmaker smartly takes the Chris Marker route, avoiding explanatory voiceover for the rather physical Hindu ritual he photographs and instead holding it at a slightly mystifying – but never exoticizing – distance. Widmann’s film is about this distance, the chasm between experience and knowledge that prevents the observer from experiencing what the observed is experiencing, however understanding he might be. Fictitious Force’s considered reflexivity carefully circumvents the all-too-common trap of conflating the subjectivities of the photographer and the photographed.

In Fictitious Force, Widmann incidentally poses himself the age-old challenge of ethnological cinema; how to film the Other without imposing your own worldview on him? The filmmaker smartly takes the Chris Marker route, avoiding explanatory voiceover for the rather physical Hindu ritual he photographs and instead holding it at a slightly mystifying – but never exoticizing – distance. Widmann’s film is about this distance, the chasm between experience and knowledge that prevents the observer from experiencing what the observed is experiencing, however understanding he might be. Fictitious Force’s considered reflexivity carefully circumvents the all-too-common trap of conflating the subjectivities of the photographer and the photographed. Fashioned out of footage that the artist shot during his visit to the titular natural reserve in Ontario, Fish Point comes across as an impressionist cine-sketch of the locale. The film opens with Daichi Saito-esque silhouettes of trees against harsh pulsating light – near-monochrome shots that are then superimposed over a slow, green-saturated pan shot of a section of a forest. This segment gives way to a passage with purely geometric compositions consisting of alternating browns and greens and strong horizontals and verticals. Forms change abruptly and tints become more diffuse and earthly. We are finally shown the sea and the horizon, with a rough map of the area overlaid on the imagery.

Fashioned out of footage that the artist shot during his visit to the titular natural reserve in Ontario, Fish Point comes across as an impressionist cine-sketch of the locale. The film opens with Daichi Saito-esque silhouettes of trees against harsh pulsating light – near-monochrome shots that are then superimposed over a slow, green-saturated pan shot of a section of a forest. This segment gives way to a passage with purely geometric compositions consisting of alternating browns and greens and strong horizontals and verticals. Forms change abruptly and tints become more diffuse and earthly. We are finally shown the sea and the horizon, with a rough map of the area overlaid on the imagery. A music video for a song that reportedly riffs on a holy chant and the traditional cry of the local ragman, Ye’s film starts out with shots of old women and men lip-syncing to the titular melody before turning increasingly darker. The rag picker of the poem progresses from accepting material refuse to buying off diseases, emotional traumas and even intolerable human characters. Ye builds the video using shots both documentary and voluntarily-performed that portray everyday life in Taiwan as being poised between tradition and modernity. The junkman of the film then becomes a witness to all that the society rejects and, hence, to all that it stands for.

A music video for a song that reportedly riffs on a holy chant and the traditional cry of the local ragman, Ye’s film starts out with shots of old women and men lip-syncing to the titular melody before turning increasingly darker. The rag picker of the poem progresses from accepting material refuse to buying off diseases, emotional traumas and even intolerable human characters. Ye builds the video using shots both documentary and voluntarily-performed that portray everyday life in Taiwan as being poised between tradition and modernity. The junkman of the film then becomes a witness to all that the society rejects and, hence, to all that it stands for. Set in a suburban Mumbai slum, Bhargava’s film takes a look into one of the reportedly many carrom clubs in the area where young boys come to play, smoke and generally indulge in displays of precocious masculinity. Where Imraan, the 11-year-old manager of the club, seems reticent before the camera, his peers and clients are much more willing to perform adulthood in front of the filming crew. While some of them are acutely aware of the intrusive presence of the camera, urging their friends not to project a bad image of the country, the film itself seems indifferent about the ethics of filming these youngsters, asking them condescending questions with a problematic, non-committal non-judgmentalism.

Set in a suburban Mumbai slum, Bhargava’s film takes a look into one of the reportedly many carrom clubs in the area where young boys come to play, smoke and generally indulge in displays of precocious masculinity. Where Imraan, the 11-year-old manager of the club, seems reticent before the camera, his peers and clients are much more willing to perform adulthood in front of the filming crew. While some of them are acutely aware of the intrusive presence of the camera, urging their friends not to project a bad image of the country, the film itself seems indifferent about the ethics of filming these youngsters, asking them condescending questions with a problematic, non-committal non-judgmentalism. Völter’s visually pleasing and relaxing silent film is a compilation of scientific documents of cloud movement over the Mount Fuji recorded from a static observatory by Japanese physicist Masanao Abe in the 1920s and 1930s. Abe’s problem was also one of cinema’s primary challenges: to study the invisible through the visible; in this case, to examine air currents through cloud patterns. The air currents take numerous different directions and these variegated views of the mountain situate the film in the tradition of Mt. Fuji paintings. The end product is a James Benning-like juxtaposition of fugitive and stable forms, a duet between rapidly changing and unchanging natural entities.

Völter’s visually pleasing and relaxing silent film is a compilation of scientific documents of cloud movement over the Mount Fuji recorded from a static observatory by Japanese physicist Masanao Abe in the 1920s and 1930s. Abe’s problem was also one of cinema’s primary challenges: to study the invisible through the visible; in this case, to examine air currents through cloud patterns. The air currents take numerous different directions and these variegated views of the mountain situate the film in the tradition of Mt. Fuji paintings. The end product is a James Benning-like juxtaposition of fugitive and stable forms, a duet between rapidly changing and unchanging natural entities. The most narrative film of the competition, Memorials situates itself in the tradition of 21st century Slow Cinema with its elliptical exposition, stylized longueurs, (a bit too) naturalistic sound and its overall emphasis on Bazinian realism. A young man revisits his father’s house long after his passing and starts discovering him through the objects of his everyday use, while a dead fish becomes the instrument of meditation and grieving. Though rather conventional in its workings, Memorials offers the details in its interstices fairly subtly and touches upon the usual themes of inter-generational inheritance and posthumous rapprochement, while also gesturing towards a necessary break from the past.

The most narrative film of the competition, Memorials situates itself in the tradition of 21st century Slow Cinema with its elliptical exposition, stylized longueurs, (a bit too) naturalistic sound and its overall emphasis on Bazinian realism. A young man revisits his father’s house long after his passing and starts discovering him through the objects of his everyday use, while a dead fish becomes the instrument of meditation and grieving. Though rather conventional in its workings, Memorials offers the details in its interstices fairly subtly and touches upon the usual themes of inter-generational inheritance and posthumous rapprochement, while also gesturing towards a necessary break from the past. Punprutsachat’s work is a straightforward document of the protracted rescue of a water buffalo from a man-made well on a sultry summer afternoon by dozens of village folk. Shot with a handheld digital camera and employing mostly on-location sound, the film presents to us the efforts of the villagers in chipping away at the edifice, restraining the animal from agitating and finally allowing it to go back to its herd. Natee Cheewit attempts to encapsulate the idea of eternal struggle between man and animal and, more broadly, between nature and civilization. The remnants of the demolished pit and the dog wandering about it are reminders of this sometimes symbiotic, sometimes destructive interaction.

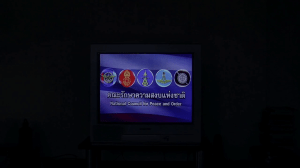

Punprutsachat’s work is a straightforward document of the protracted rescue of a water buffalo from a man-made well on a sultry summer afternoon by dozens of village folk. Shot with a handheld digital camera and employing mostly on-location sound, the film presents to us the efforts of the villagers in chipping away at the edifice, restraining the animal from agitating and finally allowing it to go back to its herd. Natee Cheewit attempts to encapsulate the idea of eternal struggle between man and animal and, more broadly, between nature and civilization. The remnants of the demolished pit and the dog wandering about it are reminders of this sometimes symbiotic, sometimes destructive interaction. Night Watch is reportedly set in the days following the military coup in Thailand in May, 2014 – a period of state repression dissimulated by triumphalist propaganda about reigning happiness. Chulphuthiphong’s debut film showcases one quiet night during this period. Jacques Tati-esque cross-sectional shots of isolated apartments and office spaces show the citizenry complacently cloistered in their domestic and professional spaces, much like the sundry critters that crawl about in the night. Someone surfs through television channels. Most of them are censored, the rest telecast inane entertainment. Night Watch underscores the mundanity and the ordinariness of the whole situation, which is the source of the film’s horror.

Night Watch is reportedly set in the days following the military coup in Thailand in May, 2014 – a period of state repression dissimulated by triumphalist propaganda about reigning happiness. Chulphuthiphong’s debut film showcases one quiet night during this period. Jacques Tati-esque cross-sectional shots of isolated apartments and office spaces show the citizenry complacently cloistered in their domestic and professional spaces, much like the sundry critters that crawl about in the night. Someone surfs through television channels. Most of them are censored, the rest telecast inane entertainment. Night Watch underscores the mundanity and the ordinariness of the whole situation, which is the source of the film’s horror. A rapid editing rhythm approximating the audiovisual assault of the information age, a visual idiom weaving together anime, pencil-drawing and Pink Film aesthetic and a soundscape consisting of reversed audio and noise of clicking mice and shattering glass defines Ouchi’s high-strung portrayal of modern adolescent anxieties. In a progressively sombre, cyclic series of events, a teenager navigates the real and virtual worlds that are haunted by sex and death around her. Ouchi’s pulsating, mutating forms and her preoccupation with the hyper-sexualization of visual culture are reminiscent of

A rapid editing rhythm approximating the audiovisual assault of the information age, a visual idiom weaving together anime, pencil-drawing and Pink Film aesthetic and a soundscape consisting of reversed audio and noise of clicking mice and shattering glass defines Ouchi’s high-strung portrayal of modern adolescent anxieties. In a progressively sombre, cyclic series of events, a teenager navigates the real and virtual worlds that are haunted by sex and death around her. Ouchi’s pulsating, mutating forms and her preoccupation with the hyper-sexualization of visual culture are reminiscent of  One of the high points of the festival, Scrapbook consists of videograms shot in 1967 in a care centre in Ohio for autistic children with commentary by one of the patients, Donna, recorded (and curiously re-performed by a voiceover artist at Donna’s request) in 2014. Donna’s words – indeed, her very use of the pronoun ‘I’ – not only attest to the vast improvement in her personal mental condition, but also throw light on the psychological mechanisms that engender a self-identity. For Donna and the other children-patients filming each other, the act of filming and watching substitutes for their thwarted mirror-stage of psychological development, helping them experience their own individuality, reclaim their bodies. Bracing stuff.

One of the high points of the festival, Scrapbook consists of videograms shot in 1967 in a care centre in Ohio for autistic children with commentary by one of the patients, Donna, recorded (and curiously re-performed by a voiceover artist at Donna’s request) in 2014. Donna’s words – indeed, her very use of the pronoun ‘I’ – not only attest to the vast improvement in her personal mental condition, but also throw light on the psychological mechanisms that engender a self-identity. For Donna and the other children-patients filming each other, the act of filming and watching substitutes for their thwarted mirror-stage of psychological development, helping them experience their own individuality, reclaim their bodies. Bracing stuff. Canadian animator Leslie Supnet’s hand-drawn animation piece is an extension of her previous work

Canadian animator Leslie Supnet’s hand-drawn animation piece is an extension of her previous work  According to the program notes, the project brings together a real-life DJ who has lost her job after the coup d’etat in 2014 and an actual illegal immigrant boy from Myanmar at a secluded pond in the woods to allow them to do what they can’t in real life. We see the DJ perform for the camera, talking with imaginary strangers, giving and playing unheard songs, while the boy is content in tossing stones into the moss-covered pond. Like a structural film, The Asylum, alternates between the DJ’s ‘calls’ and the boy’s quiet alienation, taking occasional albeit unmotivated excursions into impressionist image-making, to weave a vignette about ordinary people made fugitives overnight.

According to the program notes, the project brings together a real-life DJ who has lost her job after the coup d’etat in 2014 and an actual illegal immigrant boy from Myanmar at a secluded pond in the woods to allow them to do what they can’t in real life. We see the DJ perform for the camera, talking with imaginary strangers, giving and playing unheard songs, while the boy is content in tossing stones into the moss-covered pond. Like a structural film, The Asylum, alternates between the DJ’s ‘calls’ and the boy’s quiet alienation, taking occasional albeit unmotivated excursions into impressionist image-making, to weave a vignette about ordinary people made fugitives overnight. A Kiarostami-like narrative minimalism characterizes Radjamuda’s naturalistic sketch in digital monochrome of a lazy holiday afternoon. A young boy perched near the window of his house engages in a series of self-absorbed activities, while actions quotidian and dramatic, including a hinted domestic conflict, wordlessly unfold around him off-screen. A series of shallow-focus shots rally around a wide-angle master shot of the backyard to establish clear spatial relations. Literally and metaphorically set at the boundary between the inside and the outside of the house – home and the world – Radjamuda’s film is a pocket-sized paean to childhood’s privilege of insouciance and to the transformative power of imagination.

A Kiarostami-like narrative minimalism characterizes Radjamuda’s naturalistic sketch in digital monochrome of a lazy holiday afternoon. A young boy perched near the window of his house engages in a series of self-absorbed activities, while actions quotidian and dramatic, including a hinted domestic conflict, wordlessly unfold around him off-screen. A series of shallow-focus shots rally around a wide-angle master shot of the backyard to establish clear spatial relations. Literally and metaphorically set at the boundary between the inside and the outside of the house – home and the world – Radjamuda’s film is a pocket-sized paean to childhood’s privilege of insouciance and to the transformative power of imagination. The shadow of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s work is strongest in Kapadia’s three-part work about the cycles of life, death and reincarnation and the interaction between mankind and nature, between the real and the surreal. Set in various regions of India and in multiple languages and shot predominantly between dusk and dawn, the film has a beguiling though mannered visual quality to it, with its appeal predicated on primal, elemental evocations of the supernatural. While Kapadia’s superimposition of line drawings on shot footage to depict man’s longing for and transformation into nature demands attention, the film itself seems derivative and a bit too enamoured of its influences.

The shadow of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s work is strongest in Kapadia’s three-part work about the cycles of life, death and reincarnation and the interaction between mankind and nature, between the real and the surreal. Set in various regions of India and in multiple languages and shot predominantly between dusk and dawn, the film has a beguiling though mannered visual quality to it, with its appeal predicated on primal, elemental evocations of the supernatural. While Kapadia’s superimposition of line drawings on shot footage to depict man’s longing for and transformation into nature demands attention, the film itself seems derivative and a bit too enamoured of its influences. A potential companion piece to Porumboiu’s

A potential companion piece to Porumboiu’s  At least as formally innovative as Rithy Panh’s

At least as formally innovative as Rithy Panh’s  Wind Castle opens with a complex composition made of an unfinished (or destroyed) building behind a burnt crater, with the moon in full bloom. We are somewhere in the Indian hinterlands, a brick manufacturing site tucked inside large swathes of commercial plantations. Basu’s camera charts the territory in precise, X-axis tracking shots that form a counterpoint to the verticality of the trees. Noise from occasional on-location radios and trucks fill the soundtrack. A surveyor studies the area and trees are marked. ‘Development’ is perhaps around the corner. But the rain gods arrive first. Basu’s quasi-rural-symphony paints an atmospheric picture of quiet lives closer to and at the mercy of nature.

Wind Castle opens with a complex composition made of an unfinished (or destroyed) building behind a burnt crater, with the moon in full bloom. We are somewhere in the Indian hinterlands, a brick manufacturing site tucked inside large swathes of commercial plantations. Basu’s camera charts the territory in precise, X-axis tracking shots that form a counterpoint to the verticality of the trees. Noise from occasional on-location radios and trucks fill the soundtrack. A surveyor studies the area and trees are marked. ‘Development’ is perhaps around the corner. But the rain gods arrive first. Basu’s quasi-rural-symphony paints an atmospheric picture of quiet lives closer to and at the mercy of nature.